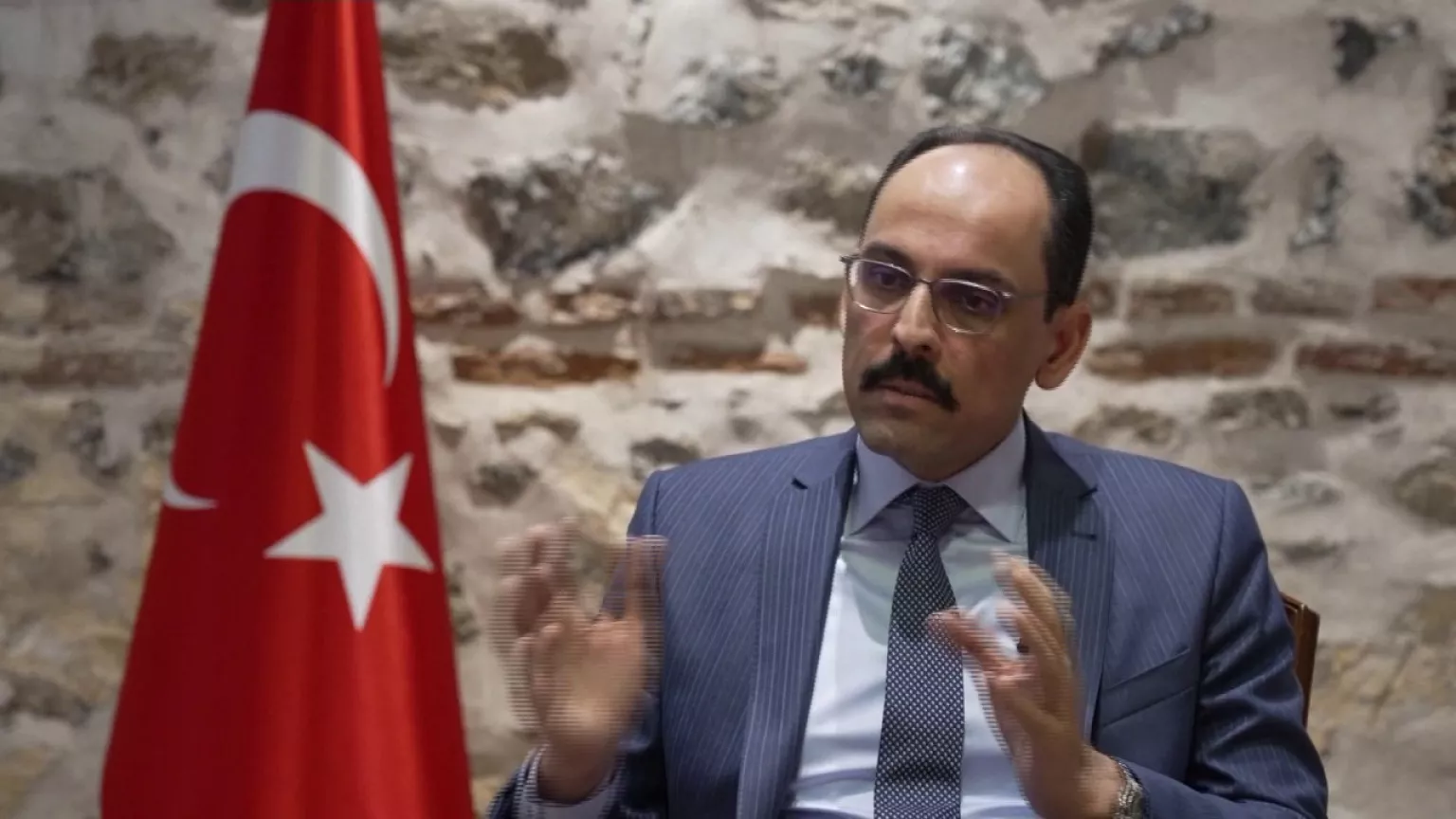

This conversation between Prof. Dr. İbrahim Kalin, then the Presidential Spokesperson and now the Director of the National Intelligence Organization (MİT), and internationally acclaimed musician Sami Yusuf is a candid exchange that traces the paths of art, spirituality, tradition, and the fundamental issues of our time. With answers that are at times philosophical and at times deeply personal, Kalin sheds light on the search for truth at both the individual and societal levels.

İnsan Publications has meticulously prepared the transcript of this valuable interview and published it as a chapter in a book. Held in 2021, this meeting was more than just a conversation; it was a record of an intellectual journey in pursuit of values, aesthetic understanding, and the “right questions” carried from the past into the present.

We present this remarkable interview to our readers.

Kritik Bakış

—————————————————————

Sami Yusuf: Mr. İbrahim Kalin, it is an honor to have you with us. I am a great admirer of yours and I follow all of your work closely. You are an intellectual, a philosopher, and you serve in one of the highest institutions in your country. On top of that, you are truly an extraordinary musician. Thank you very much for this interview.

İbrahim Kalin: Thank you for your very kind words. I honestly feel I do not deserve such praise — it is a reflection of the beauty of your own soul. Thank you. I am also a great admirer of yours. What you have achieved through your music is truly remarkable. It is something beyond music itself — a real journey that carries many of us away, shows us beautiful places, and brings light and hope in moments of darkness and despair. For that, I am deeply grateful.

Sami Yusuf: Thank you. Now, I’d like to ask you the million-dollar question: you do remarkable work in so many fields. How is it possible to do all of this? Amid the chaos, the noise, and the endless problems of the modern world, how do you maintain balance? How do you establish it?

İbrahim Kalin: I have always believed that to accomplish something, I must have a firm foundation. If I am setting out on a journey, I need to start from somewhere, have a destination, and a sense of direction. Whether it is going to the market to buy something, embarking on a journey to gain knowledge, becoming a professor, or becoming a professional in any field — you must always have a goal in mind. To reach those goals, you need a purpose, an idea. This line of thought takes me back to our traditional concept of hikmet (wisdom). When I studied Muslim philosophers, thinkers, scholars, and Sufis, I came to the conclusion that wisdom should guide our actions, our thoughts, our emotions, our minds, and our hearts. Wisdom, after all, is the fundamental purpose behind doing something. Whether you are a physicist, a doctor, a politician, a scholar, or a poet — you must have an explanation for what you do. This is part of our search for meaning, and it is meaning that drives us forward.

Sami Yusuf: Indeed, we truly cannot do anything without meaning.

İbrahim Kalin: Nihilists have claimed that there is no meaning in the modern world and that we are forced to live meaningless lives. Yet deep down, we all know there is a question about how that meaning can be uncovered, recognized, and shared with others. Yes, this is a profound question, and we also know that we cannot truly live without meaning in our lives. Meaninglessness cannot even logically serve as an answer to our search for meaning. Of course, one could say that meaninglessness itself is an answer—but that contradicts itself and is logically unsound.

I tried to understand what I was doing, and all of this led me to a multi-dimensional understanding of reality. My reading of my own existence—whether in politics, music, academia, or social issues—has shown me that reality is layered. Therefore, my answer, too, must be multi-layered. What I mean is this: if I cannot reduce reality to a single component—and logically I cannot, because the world is so rich and reality so multifaceted—then I must possess the intellectual, spiritual, and artistic capacities to respond to its different aspects.

To be honest, we are lost in this world; we exaggerate everything in a realm of noise and excessive speed. In such a state, it is clear that we need time for self-reflection. We need to pause for a moment.

Sami Yusuf: How do you do that?

İbrahim Kalin: It’s difficult, because the world rushes past you, moving so quickly. But as Tolstoy once said, “If you run through a beautiful garden, you won’t see any of the flowers.” You have to slow down a little; sometimes you must stop in front of a rose, a tulip, or a lily and bear witness to the beauty of that flower. If you simply hurry past, you are not truly in the garden—and you are missing a great deal.

You just need to slow down a bit. But of course, you must do this without neglecting your responsibilities; you cannot fall behind. That’s why you must focus on what is important. You must have priorities. Otherwise, you may spend all your hours, your entire day, on trivial matters that distract you from what truly matters. But if you have a sense of direction, a world of meaning, a purpose that drives you to do all these things, then you can manage your time better.

God, in fact, grants you blessing—He expands your time—so that your twenty-four hours suddenly become much more than just a numerical measure. There are moments—I’m sure you have all experienced this—when a single minute, ten minutes, or an hour can be worth days of work or conversation, simply because that time is so intense, so productive, so profound. This is very important.

I have always felt that the worldly time we inhabit as mortal and finite beings is but a drop from eternity. You are always connected to eternity, though you may not realize it. But when you are in contemplation, in music, in spirituality, in worship—or when you face loss, trauma, or a major life event—you feel as if you are touching eternity.

You are also connected to the eternal moment in times of deep love and compassion. Think of your love for your children, your spouse, your parents. At such moments, you feel that you are bound to that eternal instant. All of this brings blessing to your time. You become a self-motivating principle. You strive to understand what you are doing, to infuse your actions with meaning. You want to do something that you can explain to yourself and others. You say, “I am doing this because I have a good reason to do so.”

Sami Yusuf: This is quite difficult in a world where we are constantly being told there is no meaning, isn’t it?

İbrahim Kalin: Yes, that is what the modern world whispers: “The world is merely a combination of material elements—neutrons, protons, chemicals, energy, and matter. The world has no transcendent meaning. The world is nothing more than what you see on the surface; accept it as such!” Yet deep down, we know there is more to us than that, and as human beings we seek that meaning. Hikmet (wisdom) provides us with this space; it shows us how to attain that meaning and how to realize it in our lives.

In our tradition, we have the unity of truth, goodness, and beauty: logic, ethics, and aesthetics. These are realities formed of a single whole, never to be separated from one another. If something is good, it is also true, and it must be grounded in truth. If something is good and true, it must also be beautiful. And if something is beautiful, it must rest upon truth and goodness.

Of course, today we have very different priorities about what is good, true, and beautiful. We now live in a value system where profit, productivity, efficiency, and quantitative measures define success: the larger the numbers, the better it is considered. We have lost quality in our lives, and quality of life has abandoned us. That is why educators tell you to “spend quality time with your children” — as if some of the time you spend with them could be of poor quality.

Children are being poisoned by all these images and messages. Then we try to fix the damage by spending “quality time,” but by then it is often too late.

You cannot compete with the pace of the modern world; you cannot compete with social media, with fleeting moments of pleasure, with instant gratification. This quality must be built into the time you spend and into your life as a way of living. Let’s say you manage to do this for an hour a day—and I doubt many people can even do that—still, because of work schedules and daily routines, you may lose it all.

This is why wisdom, in the traditional sense, reminds us that what we do must be grounded in reality. It shows us what is logically right. Our actions should rest on ethical goodness and virtue, and they should reflect the beauty of our existence. Aesthetically, we should surround ourselves with beautiful things so that our hearts and minds can work in harmony. Let us remember: beauty is never a luxury.

Sami Yusuf: In the modern world, beauty has become something that is bought and sold.

İbrahim Kalin: It has been commercialized. Beautiful things—beautiful objects, beautiful homes—have turned into expensive items only the wealthy can afford. This is very wrong. In the traditional sense, beauty was never a commercial product. For example, when a mosque was built or a carpet woven, it was not made to be sold or turned into a commodity, but for its sacred meaning and beauty. Of course, in that world too, there was a sponsor, and it was paid for. But it had its own aesthetic logic and was never an object for sale. Calligraphy, music, architecture—all of these were meant to help us in our search for meaning and to add quality to our lives.

When we listen to music, we see that all those musicians are on a journey. For example, in the Western world, we see it in composers like Corelli, Vivaldi, Telemann, and Bach; in the Muslim world, in musicians like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Umm Kulthum, Neşet Ertaş, and Âşık Veysel. They show us the path they have traveled and say, “This is what I have. If you like it, you are welcome to join me.”

This allows us to view that journey through different experiences. In other words, all of this gives us a sense of unity. We begin to look at everything with a more unifying perspective. Yes, I am a government official, I write books, I try to make music, and I try to explain to people what I do. The common effort in all of this is to show that what I do has meaning—both for myself and for others.

Sami Yusuf: You do more than just try to make music.

İbrahim Kalin: Thank you, that’s very kind of you. It’s wonderful to hear that from you. In the end, all of these things only gain meaning when they come together. If you separate them into categories, they lose their wholeness. We all want to live a life of integrity—not only intellectually, but also with our hearts and emotions.

Sami Yusuf: You’ve said so much. Everything you say opens a new door. You’ve spoken philosophically, which is wonderful; I’m a student in this field. You are a master and an accomplished teacher. You mentioned different realities. This reminds me of a saying from one of our wise men: “What is lacking in today’s world is deep knowledge of the essence and nature of things.” What, as you describe it, are the multiple layers of reality within reality?

İbrahim Kalin: That is a very fundamental question. Reductionism is one of the philosophical illnesses of the modern world. We tend to reduce a vast system to one of its components, thinking that this will help us control it. This is, in fact, an exercise in control. If you keep something simple, then you can take control and manipulate it. Unfortunately, this has been the driving force behind much of the reductionist scientific thinking in the modern world, because modern capitalism is driven by the idea of control. The logic is: “If I can control you, I can define you. Then I can sell you more products.” It sounds terrible, but this is the reasoning behind it all.

All the statistical research, the psychological studies on social media, behavioral patterns, algorithms, trends… they are all about understanding what you like and what you don’t like, working on you so they can influence your preferences and habits.

Sami Yusuf: And in the end, they present me with options and sell me more products, right?

İbrahim Kalin: That is modern capitalism. Control becomes a function of capitalism. Science, knowledge, research—all of these turn into tools for controlling you, the customer. A person is seen as a valuable, meaningful being only when he or she is a “customer” who can be sold a product. In the modern world, we are no longer beings who carry the divine breath (nefha) in our souls; we are merely customers. For capitalism, there are only two types of people: customers or potential customers.

The problem of control is linked to simplicity: if I can keep something simple—if I can reduce all this complexity to one or two components—then I can control everything by pressing a single button.

Do you remember what happened in The Truman Show and how the character’s life was constructed? His life was controlled in a very specific way, and he didn’t know he was trapped. He was part of the system. He was living a lie. He didn’t know that his entire world had been built only to serve television, just to sell products. In one scene, his wife comes up to him and says, “Today I want to cook you this pasta.” This is nothing more than a commercial moment. It’s inhuman. The Truman Show was filmed in 1998, almost thirty years ago. The strange thing today is that everyone seems to want to be part of The Truman Show through social media: “I want to share everything, I want to post every photo as a story. I want to gain people’s approval and live another life on social media, in virtual reality…”

Sami Yusuf: What has happened to our privacy, to our identity?

İbrahim Kalin: You redesign yourself every day according to the latest fashions and trends, and with all these motives you stop being yourself. In fact, modern capitalism pushes you to do this so it can control you. The point is, reality is a much more complex phenomenon than something that can be reduced to just one of its parts. As our Muslim philosophers—and Heidegger in the Western tradition—have said, existence (vücûd), in the philosophical sense, is more than the sum of its individual entities. I am more than the collection of my organs. I am more than my hands, my feet, my eyes. Yes, they are part of me, but when they come together, I am more than my organs. You cannot reduce me to my hand, my eye, or my ear. I am a whole. That is the nature of reality, and so I must try to understand reality on different levels. Indeed, the whole is always greater than the sum of its parts.

At the material level, I have tools for understanding physical things—like moving objects. That is how I respond to objects. At the level of ideas, I use my mind, and that is how I respond to reality. At the level of imagination (ʿālemü’l-hayal), I travel between different planes of reality. Poetry, music, religion, metaphysics, novels—all of these correspond to certain aspects of reality.

If I reduce all this complexity to a single element, I lose the incredibly rich nature of reality, which I believe is something we have forgotten in the modern world. And we forget that simplicity is not the same as reductionism. You can be very simple and yet hide incredible complexity behind that simplicity. As the saying goes, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

You want to present something simply without reducing it to a single element. Like your music, for example—you say something, and the idea and emotion in that song set a journey in motion. You invite us to join you there. Sometimes musicians feel this: the most perfect moment in a melody is often the simplest one. In my view, this is actually a reflection of heavenly sounds—either bringing them here or they themselves arriving here with their eternal voices.

Sami Yusuf: That’s a wonderful comment…

İbrahim Kalin: Whenever I hear musicians—fascinating composers—I feel this way. I imagine them rising toward the sky, gathering something from there, and then performing it. This strikes me as deeply moving, profoundly meaningful. Such a level cannot be reduced to a set of physical or chemical actions or reactions in my brain. Yes, these processes occur, but to claim that everything is merely a matter of chemical activity in the mind is, to me, an insult to human dignity.

Sami Yusuf: Each of these conclusions opens new doors for questions. There is one in particular I would like to ask: why did the process of secularization occur in the West? And why was the trajectory somewhat different in the Islamic tradition, in Hindu civilization, and in other civilizations and traditions?

İbrahim Kalin: In short, the rise of modernity was entirely tied to the failures of Christian theology and traditional Christianity in the West. When the Christian churches stopped providing convincing answers—when they lost the wisdom to explain how things happen—other spaces opened up. The Enlightenment spread first to Europe and then to the rest of the world, becoming the dominant ideological current and philosophical outlook.

Of course, this is a long history and an important part of our own story, because we were strongly influenced by it. Our minds, the words we use, our terminology—all were shaped by these broad generalizations. For example, they refer to the Middle Ages as the “dark ages.”

Sami Yusuf: They weren’t that dark.

İbrahim Kalin: There were dark moments, yes, but there have been dark moments in the history of modernism as well: genocides, two world wars, chemical weapons, weapons of mass destruction. These are extremely dark realities, but we do not call this era the “dark ages.” On the contrary, we call it the “information age” and many other names.

The truth is, whenever a great tradition stops asking the right questions, it begins to die. This is true for all traditions. The same thing happened in the Islamic tradition. For a time, members of the tradition—its intellectuals—stopped asking the right questions, saying things like, “We don’t need this. It will take us too far. We will lose our faith.” You cannot halt human thought in the name of preserving faith. If you do so, faith becomes devoid of content and loses its ability to persuade.

Sami Yusuf: And if it loses that, it becomes emotional.

İbrahim Kalin: Yes, it becomes purely emotional. If, when you are challenged on an intellectual basis, you cannot give good and convincing reasons for why you believe in this religion, then faith turns into an emotional matter—and that is a grave danger for faith. Because once you remove that emotional element or replace it with something else, it is permanently lost. You cannot recover it. This is why you must keep the intellectual principle strong. Unfortunately, the Christian tradition lost this in the 17th and 18th centuries; it could not produce new answers.

To stop asking questions is a great danger for all traditions. And if you begin to ask the wrong questions, that is another problem—you lose your way. You must find the right questions; you cannot avoid them. That is how you keep a tradition alive and dynamic. Tradition does not mean mummifying the past. Nor does it mean holding only nostalgic ideas about the past. Tradition means that something of great value has been given to you, and now you are expected to do something with it. If you do not know what to do with it, you are in fact betraying the tradition; you are failing to do what is expected and what is right.

If you have accepted a tradition, revive it and strengthen it. Give it life; become part of a living tradition by adding something to it. Otherwise, tradition becomes mere history. What we need is not history—we need a living tradition that can shape our present and our future.

We can only benefit from the Islamic tradition through such an interactive and dynamic approach. Yes, there are many great figures in this tradition—from al-Farabi to Mulla Sadra, from the great Andalusian musician Ziryab to the architect Sinan. But we do not want to merely admire their work; we want to learn from them, engage with them. We want to ask questions of al-Ghazali and al-Farabi and receive answers from them. We should pose to them the questions of today—our own age—and seek logical answers through both our minds and our hearts.

Sami Yusuf: I love the way you play the bağlama. The last piece I heard from you was by Âşık Veysel. When I looked into him a bit, I was captivated—I didn’t know much about his life. By the way, your voice has such a beautiful warmth, a rich mid-tone, and I really enjoy it… I think you should make more music. You should release more content.

İbrahim Kalin: First of all, thank you once again for these kind words—especially coming from you, they mean a great deal. Through your music, you have given us so many different and beautiful states of mind, filled with deep thought, beauty, and compassion. Thank you for that. Your music has gone far beyond the Islamic world; it has become a global voice, and in that sense you have achieved a great deal through your art. In a way, this is in harmony with the spirit of music itself.

As you know, the word “music” comes from muse, meaning “that which inspires.” When you possess the notion of inspiration, you are no longer the master of what you do—you receive something and share it with others, and this in fact makes you humble. If you are a true musician, or a master of anything, you cannot be arrogant. You know that your talent has been bestowed upon you. Your duty is to use it in the most effective way and to perform it with humility so that it becomes a blessing. In this way, what you create multiplies spiritually; when you share it, it does not diminish.

Sami Yusuf: It multiplies because it is also contagious, isn’t it?

İbrahim Kalin: I have always felt that music opens many doors in my mind and helps me better grasp the meaning of what cannot be expressed in words in my soul. There are moments when you reach a place beyond description—moments when there are simply not enough words in your mind, soul, or heart to express what you hold inside. When you reach that indescribable point, you begin to say the most beautiful things.

You have to go to that border beyond words, so that you can begin to speak in silence. Sometimes the most beautiful conversations happen quietly, without words. When you can remain silent in the company of friends, that is the most beautiful conversation, and no one asks, “Why are we silent? Has something gone wrong?” On the contrary, you enjoy the silence together—because our minds and souls are in the place where the undefinable permeates. It is saying much by not speaking.

For me, music is a profoundly important field. The ability to express emotions, ideas, and states of being without uttering a single word is precious. You press certain notes, and you are saying something—it draws you in, and you begin to focus on that moment. Especially when playing with others, there is a beautiful harmony that emerges from that collaboration. You are yourself—as a singer, a composer, or a virtuoso—yet you are also with others. You don’t lose your individuality; you play together.

In fact, when you play with good musicians, you realize that they bring out the best in you. They invite you, they enliven you, and sometimes they captivate you. There are moments when, as part of an orchestra or a group, you feel the perfect harmony of community and individuality. You are part of something greater than yourself without losing who you are. And often, there is an element of improvisation in this.

When you play with other musicians, you feel: “Could I live my whole life this way? Right now I am not just playing this music—I am part of a larger reality: my community, my family, my friends, my university, my country, humanity as a whole. Could I have that sense of flow with others without losing my self, without arrogance?” Because I know that my talent becomes more valuable when others share in it.

All of these are things that inspire me when making music. Listening to music, playing an instrument, conveying the inexpressible through music—it says far more than any word you could choose.

Sami Yusuf: You still haven’t explained how you manage to do all of this. Anyone familiar with your work and life knows that you are productive, very busy, and yet you accomplish so much despite that busyness. How can we attain this kind of blessing?

İbrahim Kalin: When you are constantly on the move, you begin to discover how to do many things at once. When I was at the university, teaching as a professor, I had my own time and could plan my own work. I could spend hours in my office or library. I no longer have that luxury.

When I travel—whether for official meetings or other reasons—I have found that there are windows of time in which I can do different kinds of work. I developed the habit of doing things on planes, in hotels, while in motion. If I am writing something, I always have my books, my notes, and my computer with me. I cannot carry my saz—my musical instrument—everywhere, but it is always in my mind and in my heart. Even from a distance, symbolically or imaginatively, I am always playing it.

You learn how to do these things within your limited time, and you give priority to what you consider important. You spend less time on things that are relatively less important. For example, you spend less time on social media or television. I’m not saying don’t do them at all—surely we cannot completely avoid them—but we can keep them at a reasonable level, to the extent they are necessary for our lives.

The main thing is to focus on what is truly lasting and important. Because all of us want to connect ourselves to something enduring—not to something that will disappear in five minutes or two days. We want to remain connected to things that give us a sense of lasting satisfaction. Otherwise, fleeting pleasures, physical or material enjoyments, and such things have no end. And not only do they have no end, they also offer no deep spiritual fulfillment. There is no answer to be found in searching for profound meaning in any of them.

Sami Yusuf: Thank you so much for honoring us with your presence. Considering that we are in the middle of a pandemic, we are living through a time quite unlike anything we’ve seen before. If possible, it would be wonderful to hear a few thoughts from you about this as well.

İbrahim Kalin: COVID-19 has been a great test for all countries. Such a major catastrophe has also shown us that there is no hierarchy between societies. It makes no difference whether you are rich or poor, Eastern or Western… This virus, invisible to the naked eye, brought the entire global system to its knees—and the entire global system tested positive. That is why we must act with seriousness if we are to draw lessons from this process.

It was good that we began to isolate ourselves—social distancing, masks… But even more important is the ability to engage in self-reflection without isolating oneself from others. If we can quarantine ourselves from everything base and ignoble, if we can cultivate this, we can live materially with less—and I think this is one thing we learned during the pandemic: less is better.

As Ernst Friedrich Schumacher said many years ago, “Small is beautiful.”(1) Once again we are reminded that what is small is possible, beautiful, and more meaningful. In truth, we didn’t need a global pandemic or a catastrophe like this to understand that. As human beings, we can live with less dependence on material things that are lower than us. Let us put our trust in something higher than ourselves, not in what is beneath us—for what is lower will pull us down.

Therefore, we should read this entire process as a collection of moments for thorough and deep reflection on our core purpose and the meaning of our lives. We have been given so many blessings. It is time to realize the value of the fact that we can breathe, speak, see, and hear. We must appreciate the worth of seeing the daylight, hearing the songs of birds, touching the fruit we will eat, tasting a cherry or an apple—and never take them for granted.

- See. E. F. Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered (London: Blond & Briggs, 1973).