The pro-democracy movement marked the death knell of Arab nationalism and unintentionally quickened a shift of regional power toward the Gulf States.

In early December, Tunisian authorities arrested a well-known opposition activist. Human Rights Watch noted that Ayachi Hammami, “a lawyer and rights defender, was arrested on December 2 in his home in a suburb of Tunis. Earlier that day, Hammami’s lawyers had filed an appeal before the Cassation Court, the highest court in Tunisia, and an additional request to suspend the verdict execution pending a final decision.” The crackdown on various critics and opposition elements is another step by the current leader, President Kais Saied, to cement control.

The arrests in Tunisia are an example of how one of the central countries of the Arab Spring has transitioned from a nascent democracy back to a form of authoritarianism. The Arab Spring began after Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in December 2010. A month later, after protests swept the country, Tunisian President Ben Ali fled into exile. He had been in power since 1987 and had become a symbol not only of the Tunisian regime but also of Arab nationalism and secularism that had emerged in the Middle East after the colonial era.

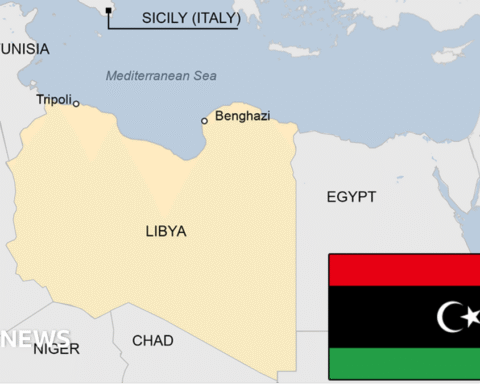

The fall of Ben Ali quickly created a domino effect, leading to the fall of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in February 2011 and Libyan dictator Muammar el-Qaddafi in October 2011. As the Arab Spring progressed, it changed form. While Tunisia appeared to transition relatively peacefully toward democracy, the changes in Egypt and Libya portended a more turbulent future.

In May 2012, Egypt held elections, resulting in the Muslim Brotherhood’s victory and the presidency of Mohamed Morsi. His rule was short-lived. In July 2013, after mass protests, he was overthrown by the army, and General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi assumed power. Now-President Sisi continues to rule Egypt to this day.

In Libya, the overthrow of Qaddafi was particularly bloody, with rebels brutally slaying the former dictator. Later, Libya sank into a conflict that pits the eastern half of the country under General Khalifa Haftar against a rival government in Tripoli. The tragedy in Libya unfolded gradually. In 2012, for instance, US ambassador Christopher Stevens was murdered by extremists in Benghazi. The rise of Haftar, backed by Egypt, came as a response to this chaos. Egypt sought to push back against the same extremism that Sisi believed had threatened Egypt in 2012.

This dynamic between civil conflict, extremism, and authoritarianism has defined the last decade and a half since the Arab Spring. The Arab Spring was a popular reaction to the superannuated nationalist regimes that had arisen between the 1950s and the 1970s in the Arab world. These included the Assad regime in Syria and the Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq. It also included Ali Abdullah Saleh in Yemen.

Opposing the nationalist governments stood the Arab monarchies in the Gulf, Jordan, and Morocco. A third Islamist bloc emerged in the 1980s that attracted young men. These movements, some of them linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, spanned a variety of parties and terrorist groups. For instance, extremists assassinated Egyptian president Anwar Sadat in 1981. Hafez al-Assad crushed a Brotherhood rebellion in Syria in 1982.

The result of these trends, nationalism, monarchism, and religious extremism, left most average people with very few options for political participation. The Arab Spring initially seemed like a way to throw off these historic trends and create new democracies and polities in the Middle East. However, the power vacuum led to civil war and the rise of extremist groups like ISIS. In 2014, ISIS conquered a wide swath of Syria and then invaded Iraq, committing massacres and genocide of minorities.

In essence, the last decade in the Middle East has been a long struggle to reverse the Pandora’s box that the Arab Spring opened. Arab regimes have pursued three separate strategies to bring this about. One approach, as demonstrated in Egypt and Tunisia, was simply a return to a kind of authoritarianism that existed before 2011. In the Gulf, some countries have slowly liberalized on certain issues while remaining monarchies. A third approach might be found in Syria, where the Assad regime finally fell on December 8, 2024. Syria now has a chance to fulfill the hope of the Arab Spring if Damascus can find a way to transition to democracy.

The question facing the Middle East now is whether the Damascus model will lead to long-term change. The Syrian rebel Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) group, which came to power in December 2024 in Syria, has its roots in extremist groups such as Al Qaeda. However, HTS re-branded itself over the years. Nevertheless, Syria remains divided. The US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces in eastern Syria are a largely Kurdish-led force that helped defeat ISIS. They are also left-leaning, while the government in Damascus is more Islamic and conservative. Can Syria come together and unite these various groups?

Another challenge for the region centers on the post-Gaza war era. A ceasefire in Gaza came into effect in October 2025. The Israel-Palestinian conflict has not changed greatly since the Arab Spring. This is in part due to the intensity of the conflict, which meant the Spring did not impact Palestinian politics as much as it did in other countries. Nevertheless, the larger changes in the region have affected Israel. Weapons smuggled from Libya via Egypt likely fueled the 2012 and 2014 war between Israel and Hamas.

The Arab Spring was a turning point in the region because it accelerated the end of the Arab nationalist regimes that had defined the Arab world since the withdrawal of European powers after World War II. These nationalist regimes had for too long relied on insubstantial and illusory rhetoric and were not well-suited for the challenges of the twenty-first century.

The survival of the monarchies has meant that the center of power and gravity has shifted from historic Arab capitals such as Cairo, Damascus, and Baghdad to Doha, Abu Dhabi, and Riyadh. Economically, the same trend has occurred; the Gulf is the most powerful economic center in the region. Fifteen years after the protests began, the major Arab states are still recovering from a decade and a half of conflict and instability. It will take another decade for the recovery to be complete.

*About the Author: Seth Frantzman

Seth Frantzman is the author of Drone Wars: Pioneers, Killing Machine, Artificial Intelligence and the Battle for the Future (Bombardier 2021) and an adjunct fellow at The Foundation for Defense of Democracies. He is the acting news editor and senior Middle East correspondent and analyst at The Jerusalem Post. Seth has researched and covered conflict and developments in the Middle East since 2005 with a focus on the war on ISIS, Iranian proxies, and Israel’s defense policy. He covers Israeli defense industry developments for Breaking Defense and previously was Defense News’ correspondent in Israel. Follow him on X: @sfrantzman.

Source: https://nationalinterest.org/blog/middle-east-watch/the-arab-spring-15-years-later