Abraham Kuyper’s thoughts on Islamic civilization have much to contribute still to the debates surrounding Muslims’ place in the West.

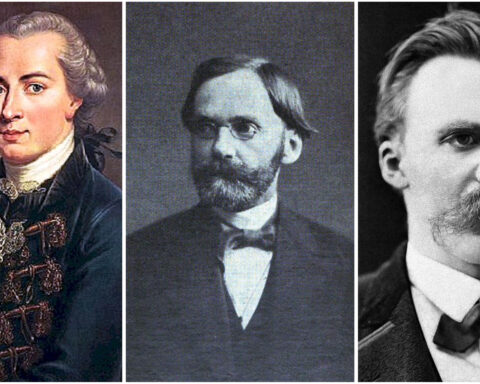

Abraham Kuyper is remembered as a titan of Dutch politics, a preeminent Reformed political theologian, and someone many consider the ideological father of the Protestant strain of Christian democracy. In Kuyper’s vast output, comprising over 200 books and 20,000 articles, outstanding is his Om de Oude Wereldzee, “On the Old World-Sea,” an impressive travelogue of Kuyper’s tours of the civilizations along the Mediterranean, from Crimea to Spain. In this journalistic endeavor, Kuyper explores his thoughts on Islam and Islamic civilization in a manner only obliquely indicated in his other works, notably the Stone Lectures, where “Islamism” is briefly considered as an alternative worldview to Christianity, in the same vein as modernism. Om de Oude Wereldzee, translated into English as On Islam, offers a historical perspective on Kuyper’s relation to the Islamic world but also places Kuyper as of particular value to contemporary Islamic political thought.

In his first chapter, titled “The Asian Danger,” Kuyper identifies almost immediately “the dormant unity of monotheism in its threefold manifestation.” He rightly addresses the immense violence and persecution that the Abrahamic faiths have suffered at each other’s hands, but predicts that “once the conflict between monotheism and polytheism comes into the foreground, the Asian monotheist will fraternize with his European counterpart.” This understated and hopeful posture toward Islamic civilization is a consistent reference point for Kuyper. Despite exoteric theological and cultural differences, Islam may prove a worthy partner for the Christian West in combating the forces of moral and political disorder in our times.

The affinity between Western Christendom and Islam, Kuyper envisions, is threatened by two global trends: European hostility to Islam and, as a consequence, the budding relationship between Islam and anti-colonial and anti-Western rising powers like Japan. Europe’s “harsh treatment of the Muslim” has caused an Islamic enchantment with “Asian liberation,” a tendency that would flower in the third-worldism of the Cold War, where Muslim freedom fighters found natural friends in Mao, Tito, and other nonaligned communist powers against Western colonialism. The contemporary cooperation between the Islamic fundamentalist regime in Tehran and Venezuela shows Kuyper’s fear vindicated. Despite the tremendous promise of Islamic nations as allies of the West, this friendship relies on Western beneficence and fair treatment, a worthy reminder as many European nations struggle to integrate their own Muslim minorities.

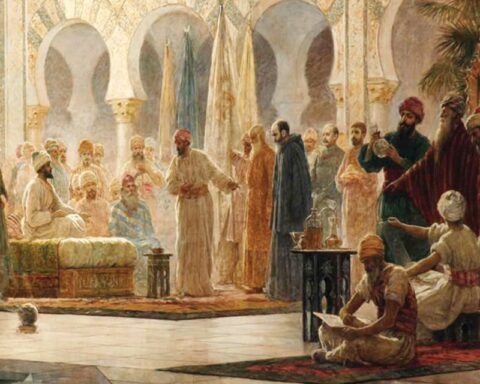

Kuyper also saw in Islam the seeds of the social order he envisioned for his Netherlands. In his commentary on Islamic law and custom, he reasoned that Islam is “naturally democratic and flourishes in freedom.” Even without a visible hierarchy, Islamic piety ensures that “all who call upon Allah and his Prophet feel themselves to be part of one body.” Kuyper saw, too, in the democratic character of Islam a strong tradition of pluralism. Amid his tense concern for the persecution of Christians by Muslim polities, Kuyper nevertheless admits that the Ottoman Turks “handled their vanquished peoples by granting them a certain sphere sovereignty.” The Ottoman millet system, where minority religions were granted self-government, Kuyper considers an Islamic analog to his own prescriptions for Dutch society. In light of the modern plight of religious minorities in the Middle East and the sharp debates over Islamic rights in the West, both the Ottoman and Kuyperian models of community self-governance ought to enrich our ability to live and participate in society side-by-side.

Kuyper’s conciliatory tone toward Islam is not, however, completely uncritical. Even his admiration for Islamic civilization is colored by his firsthand experience of imperial decline in Istanbul. The organic affinity of Islam for liberty, which Kuyper underscored, is clouded by cultural malaise. He notes what he finds to be an air of sexual immorality in Islamic countries, with the Islamic community unable to thwart this “sexual danger” due to its lack of a “healthy core of civic life.” Although the concern for licentiousness does not occupy the discursive space for many Muslims today that it did in Kuyper’s life, the troubling lack of Islamic civil society—that sphere that is neither government-run nor strictly private, but cultural and voluntary—remains a matter for discussion. Kuyper also finds this absence in Christian history. In his exposition on the collapse of Christian communities in the Middle East during the Arab conquests, Kuyper writes that the faith had fallen tragically into “the hands of shrewd scholars, imperious prelates, and cunning politicians.” Just as in the Islamic struggle to control sexual behavior, Christians could not defend themselves from foreign invasion because they were utterly deprived of a civil society on which their religion could draw upon and affirm.

The deficiency of the third sector in Islamic society is far from Kuyper’s sole criticism of the Islam he observed around the Mediterranean basin. Kuyper took particular issue with the experience of Muslim women. As he saw it, “In Islam the female is merely incidental,” and “a woman exists for the man and finds in him alone her sole reason of being.” His words on the Islamic treatment of women are severe, but not out of place in contemporary Islamic women’s advocacy. Amina Wadud, an American Islamic scholar, has described her work on women in Islam an attempt “to encourage the hearts of Muslims, both in their public, private and ritual affairs, to believe they are one and equal.” Kuyper does not find this dim view of women an exclusively Islamic infirmity, however, writing that “the evil that visibly swirls around family life in a city like Paris or London has intruded into the Eastern family itself.” Kuyper’s shock at the denigration of women in the Islamic world is mirrored precisely in his revolt at the devaluation of women in the West under liberalism.

Kuyper’s travelogue concludes with a reflection on the history and future of Euro-Islamic relations. Writing in the early 20th century, Kuyper commences a discourse that would later reach its most wicked expression in Nazi ideology: the notion of a world‑historic struggle between the Aryan and Semitic races. Yet racial animosity is entirely absent from his treatment. Kuyper privileges Semitic spirituality over that of the Aryan, writing that “the Aryan element, when it tries to reign alone, impoverishes the life of the heart.” Kuyper finds the separation of European and Near Eastern cultures and peoples not only an unnatural innovation but a direct attack on the foundations of the West. He deems modernism “fundamentally nothing other than an attempt by the Aryan mind to shake off this Semitic spiritual element.” Traditional Christianity, Judaism, and Islam share a heritage as spiritual sons of Shem, a counterweight to the rising “Germanic Christ” Kuyper feared was ascendent in the Europe of his time.

Kuyper closes with an exhortation to continue missions to the Islamic world, but Kuyper’s work has a much wider evangelistic scope. Kuyper’s writing on Islam is proselytism on behalf of a free and orderly society. His appetite for public religion, minority rights, civil engagement, and women’s rights forms the basis of not only a Dutch Calvinist society but any political order that takes faith and flourishing seriously. Kuyper is unflinchingly Christocentric, but Kuyperian thought remains a latent vein of political theory waiting to be struck by Muslims in our time. The dual crises in the West and the Islamic world identified by Kuyper are the same as those experienced today, and only collaboration based on shared values will permit what Kuyper believed was at the core of every religion: “peace for the human heart.”

Source: https://rlo.acton.org/archives/127284-kuyper-and-islam.html