Source: DÎVÂN Journal of Scholarly Studies Issue 15 (2003/2), pp. 1–51

From the Middle Ages to the Modern Era:

Europe’s Discovery of Islam as a World Culture

Some late medieval and Renaissance thinkers who admired Islamic culture opposed the Christian image of Islam as a heretical religion in their works. Islamic science and philosophical culture played an important role in shaping their views. Here, I will mention only two examples concerning how Islamic philosophy and Muslim philosophers were received with interest. Our first example is Dante and his famous work, The Divine Comedy. This work is a concrete example of traditional Christian cosmology and eschatology in the Christian religious tradition, where everything is put in its place. In this entirely Christian framework, Dante places the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) and, as the second most important figure in Islam, his cousin and son-in-law Ali, in hell.[1] On the other hand, Dante suggests that there is hope for salvation for Saladin, Avicenna (Ibn Sina), and Averroes (Ibn Rushd), and thus places them in purgatory. This positive attitude towards the second group became even more evident when Siger de Brabant, who defended Latin Averroism later, was placed in the paradise as someone who kept the memories of Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina alive. In this context, Dante reveals the way he came face to face with Islam: even if Islam is rejected as a religion, its intellectual heroes must take their rightful place. Dante’s references not only to Avicenna and Averroes but also to other Muslim astronomers and philosophers in his works can be seen as a sign of his interest in Islamic philosophy and science. In the same vein, the impact of the Prophet’s ascension (mi‘raj) on Dante’s Divine Comedy has been discussed by many European scholars, and seen as an indication of Dante’s interest in Semitic languages and Arab-Islamic culture. The Spanish scholar Asín Palacios even argued that the mi‘raj served as a full model for Dante’s Divine Comedy.[2] Despite rejecting the Prophet Muhammad as required by Christianity, Dante’s interest in Islamic thought and culture is an important example that shows the possibility of intellectual and cultural interaction and coexistence between the two traditions.

Another example of the different perception of Islamic culture is the rise of Latin Averroism in the West and its dominant role in scholastic intellectual life until it was officially banned by Bishop Tempier in 1277. Even though Averroism was publicly denounced as a heretical school, it remained as evidence of the profound influence of Islamic thought in the West. Roger Bacon (1214–1294), one of the important figures of 13th-century scholasticism, stated that Muslims (Saracens) could only be overcome, if not on the religious level but on the intellectual one, by learning their languages. Albertus Magnus (1208–1280), known as the founder of Latin scholasticism, did not hesitate to admit the superiority of Islamic thought in many philosophical matters. Even Raymond Lull (1235–1316), one of the most important figures in medieval Islamic studies, argued that Islamic culture had to be studied academically and that Christian faith could be explained to nonbelievers by using rational arguments.[3] Finally, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the peak figure of classical Christian thought, could not remain indifferent to the challenge of Islamic thought, especially that of the Averroists. Moreover, Averroism was no longer a distant threat, but one represented nearby by Latin thinkers such as Siger of Brabant (1240–1284) and Boethius of Dacia.[4]

This new intellectual attitude toward Islam matured at a time when Western Europe, convinced that Islam was a rising threat, hoped that the Mongols, known among the Latins as “Tatars”, would convert to Christianity. The clergy’s hope that the Mongols would embrace Christianity as a possible way to deal with the Islamic problem became more pronounced with the missionary efforts of Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), one of the founders of the Cistercian order and a major figure in organizing the 12th-century Crusades, and Raymond Lull, regarded as the first missionary aganist Muslims. While lamenting the absence of missionary activity directed at non-Jews (Gentiles), Bernard of Clairvaux told his fellow Christians: “Are we to wait for our religion to descend to them? Who has ever come to faith by chance? If they are not preached to, how can we expect them to believe?”[5] The conversion of the Mongols to Islam during the time of Gazan and Oljaitu, the grandsons of Genghis Khan, completely thwarted these hopes of the Christians.[6] Thus, it became clear that dealing with Muslims could not rely solely on theological persuasion but also required the widespread use of philosophical methods. Interestingly, the interest of European scholars in Islamic culture and belief outside of religion in the 11th and 12th centuries contributed to the emergence of the movement that C.H. Haskins calls the “12th-century Renaissance.”[7]

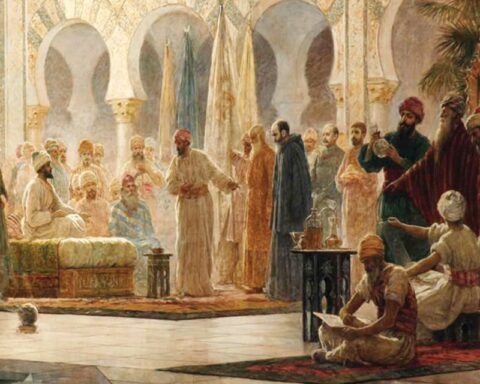

The experience of coexistence (convivencia) of the three Abrahamic religions in Andalusia occupied an important place in the Western perception of Islam throughout the Middle Ages. The translation movements centered in Toledo, the rise of the Mozarabs and Mudéjars, the spread of Islamic culture in southern Spain, and the strong inclination to see Islamic culture as superior can all be considered indicators of the various forms of interaction between Islam and medieval Europe. As early as the 9th century, a Spanish Christian named Alvaro complained of Islam’s influence on Christian youth as follows:

“My Christian brethren are so deeply affected by the poetry and romances of the Arabs that they are studying the works of Muhammadan theologians and philosophers. And in doing so, their aim is not to show that they are wrong or to refute their claims, but rather to learn an elegant and refined Arabic style. Today, it is almost impossible to find anyone reading the Holy Scriptures apart from the priests. Who today is working on the Gospels, the Prophets, or the Apostles? Alas! Even the most talented Christian youths possess no knowledge of any literature or language except Arabic. They read Arabic books with great enthusiasm, pursue studies in them, pay large sums to acquire the most famous Arabic works, and boast everywhere of their knowledge of Arab learning.”[8]

Although there were no significant changes in the perception of Islam as a religion, the interest in Andalusian Muslim culture allowed for mutual interactions in philosophy, science, and the arts. Despite the expected power tensions between different groups, Spain hosted many new ideas and the emergence of many cultural products, from Beati miniatures and Flamenco music to Elipandus’s revival of the “adoptionism” movement. The cities of Toledo, Seville, and Córdoba were respected not only as Muslim cities in the religious sense but also as centers of prosperity, refinement, and magnificent cultural exchange and transformation.[9] It is also possible to mention here the profound influence of Islamic culture and Sufism on Spanish literature, especially St. John of the Cross.[10]

Despite the noble memory of Andalus, the combative attitude that viewed Islam as heresy persisted as an unchanging element even after the end of the Christian Middle Ages and the rise of a secular worldview in Western Europe. For example, Pascal (1623–1662), the most ardent defender of Christian faith in the 17th century, was as harsh and uncompromising as his ancestors when he accused the Prophet of Islam of being a deceiver and false prophet. In the fifteenth section of his Les Pensées, titled “contre Mahomet,” Pascal expresses vividly his and his co-religionists’ feelings about Islam and the Prophet Muhammad:

“Muhammad cannot in any way be compared with Jesus. Muhammad does not speak with divine authority; his coming was not foretold, and what he did anyone could do. Jesus, however, is beyond human and beyond history.”[11]

A similar stance appears in George Sandys’ (1578–1644) Relation of a Journey begun An. Dom. 1610. Foure Books. Containing a description of the Turkish Empire, of Aegypt, of the Holy Land, of the Remote parts of Italy, and Ilands adjoyning, one of the earliest travelogues about the Islamic world. As a humanist and a Christian, Sandys viewed Islam much as Pascal did. He had no intention of altering his Christian prejudices against Islam through a “humanist” lens. His book contains important observations about the Islamic world, polemical remarks about the Qur’an and the Prophet, and, finally, appreciative evaluations of Muslim philosophers. The dilemma of rejecting Islam as a religion while respecting its cultural achievements is also reflected in Sandys’ work. In the chapter “On the Muhammadan Religion,” Sandys writes:

“We may conclude that the Muhammadan religion, having come from a worldly man, is most sinful in its designs, most worldly in its schemes, fickle and cruel in its judgments; it relies on baseless tales and intuitions, and lacks the common sense and wisdom that the sacred hand has emphasized in its Works, it entices men by presenting worldly pleasures as sweet and attractive, promises their realization in this life and in the hereafter, and enforces them with tyranny and the sword. To speak against it is sufficient cause for death. In the end, the Muhammadan religion has grown without a sense of virtue, reason, science, freedom, or refinement; it renders the earth barren, desolate, and uninhabited. It is not from God (except being as a scourge), nor can it lead anyone to God.”[12]

As someone who rejected the religious institutions of Islam, Sandys employed the tactic of pitting Muslim philosophers against Islam, as was common in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The assumption behind this is the belief, expressed out loud by someone as famous as Roger Bacon, that Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd) had secretly converted to Christianity or had remained Muslims only out of fear of persecution. For many Europeans, this method was the most reasonable way to explain the extraordinary talents and achievements of Muslim philosophers and scientists against a religion that the medieval West abhorred, ignored, and rejected. Thus, while Sandys dismisses Islam as an irrational religion because of the “theory of double truths” attributed to Ibn Rushd by St. Thomas Aquinas, he speaks highly of Ibn Sina:

“Avicenna, as a Muhammadan, in his books De Anima and De Almahad, dedicated to a Muhammadan ruler, praises Muhammad as the Seal of the Sacred Law and the last of the prophets. But this same Avicenna, setting aside his outward Muhammadan identity, in the manner of a philosopher, establishes in his Metaphysics a sharp conflict between the truths of religious belief received from the prophets and the understanding based on evidence. (…)According to Ibn Sina, it is noteworthy that something that is true in their religion is completely contrary to pure and evidential reason. In recognition of the honor of the Christian faith, it must be said that what is true in religion cannot be the opposite of what is true in philosophy, and this is a fact accepted by the High Council and esteemed by all. For the truths of religion are always above reason, but never contrary to it.”[13]

A similar line of thought can be seen in Pierre Bayle’s monumental work, Dictionnaire historique et critique (Historical and Critical Dictionary, 1697). Bayle (1647–1706) was one of the most important figures of the Enlightenment. His skeptical approach to knowledge left a deep impact on the French Encyclopedists and was defended by Diderot and other rationalist philosophers of the 18th century. In Bayle’s Dictionnaire (Dictionary), aptly described as the “arsenal of the Enlightenment,” there is a remarkably detailed 23-page entry titled “Mohammed.” By contrast, the entry on Averroes covers only seven pages, while that on al-Kindi amounts to half a page. Bayle, who is cautious in conveying Christianity’s slanders about Islam and the Prophet Muhammad, rejects absurd and unfounded stories such as the Prophet’s grave being in the air and his dead body being eaten by dogs, which is considered a sign of divine curse and punishment as well as a sign that he is the antichrist. According to Bayle, we already have enough material to accuse the Prophet:

“I will not deny that our overly zealous polemicists have sometimes been unfair. To portray Muhammad as a loathsome figure and make him an object of ridicule, they make use of legendary tales. But in doing so, they harm justice and honesty, which are necessary for all men, good and bad alike, and for the whole world. We cannot accuse a man of what he did not do, and thus we cannot oppose Muhammad on the basis of fanciful stories related not by himself but by some of his followers. We already have enough evidence against him. He must be judged only by his own faults, and not held responsible for the rash and fanciful inventions of some of his followers.”[14]

After these cautious statements, however, Bayle joins his European colleagues in portraying the Prophet of Islam as a lustful, quarrelsome deceiver and a “false teacher.” In The Dictionary, Prophet Muhammed is treated much as he had been in medieval Christian polemics. Quoting the authority of Humphrey Prideaux, Bayle writes:

“Muhammad was an impostor, and this imposture was driven by his passions. (…) His love affairs are most curious. He was extremely jealous. Yet he treated his beloved wife Aisha with remarkable gentleness and patience. (…) I prefer to agree with the general opinion that Muhammad was an impostor, for, apart from what I shall say elsewhere, his insinuating manners and skillful speeches clearly show that he used religion as a tool for his own advancement.”[15]

While Bayle’s article does not constitute a major advance compared to the terrifying portrayals of earlier centuries, it does contain important observations on Islamic culture, based on the travelogues available in his time. Bayle, for example, highlights the humility of Turkish women, in contrast to the dominant Western stereotypes of Islam and Muslims, as evidence of the “normality” of Muslim culture. He praises the Muslim nation for its religious tolerance, while sharply condemning medieval Christians for persecuting their fellow believers. Like his predecessors and many people who think like him, Bayle explains Muslim history in a conflict with the commandments of Islam and sees the glory and honor in Muslim history as the result of the Muslim nation deviating from the principles of Islam rather than adhering to them. Bayle writes:

“Muhammadans, according to the principles of their faith, are obliged to use violence and destroy other religions. Yet, as has been the case for centuries, Muslims treat those of other faiths with tolerance. Among Christians there is no rule but only commands and sermons. But when they lose their senses, they set everything on fire and put to the sword those who are not of their faith. If we look at what Muhammad said, ‘When you encounter unbelievers, kill them, cut off their heads, keep them in prison and chain them until they pay their ransom, or release them if you will.’ He ordered ‘Do not leave them in peace until they lay down their arms and submit to you.’ Yet it is true that the Muslims (Saracens) soon turned away from violence. The Greek and Orthodox churches have remained under Muhammad’s yoke to this day. They have always had their bishops, abbots, councils, disciples, and priests. It must be acknowledged that if Western princes had been the masters of Asia, unlike the Turks and Muslims (Saracens), there would no longer be any Greek church today, nor would they have shown the same tolerance to Muhammadans that they showed to Christians.”[16]

Toward the end of this entry, Bayle refers to the work of Humphrey Prideaux of Westminster (d. 1724), stating that sufficient information on Islam can be found in his book, whose long title speaks for itself: The true nature of ımposture fully display’d in the life of Mahomet: with a discourse annex’d for the vindication of christianity from this charge. offered to the considerations of the deists of the present age. Published in 1697, this was one of the harshest and most scathing attacks on Islam in the Enlightenment era. Ranked among the bestsellers of the 18th century and reprinted many times in the 19th, it offers valuable insights into Enlightenment perceptions of Islam.[17]

Uncompromising rationalism and open hostility to religion reinforced the medieval perception of Islam as a religious worldview. Attacking Islam was seen as an effective way to challenge this definition of religion itself. This attitude is especially clear in Voltaire (1694–1778), one of the most widely read figures of the Enlightenment. While Voltaire adopted a somewhat less hostile stance toward Islamic culture, he nonetheless perpetuated the earlier Christian depictions of the Prophet Muhammad. In his famous tragedy Fanatisme ou Mahomet le prophète, Voltaire presents Muhammad as the very prototype of fanaticism, cruelty, imposture, and lust. Readers were already familiar with such portrayals from much earlier periods. The only novelty may have been Voltaire’s own invented stories about the Prophet of Islam. In a letter to Frederick of Prussia, Voltaire wrote:

“(…) that a camel driver should stir up revolt in his own city, boast of entering heaven, take pride in receiving this incomprehensible book which insults common sense on every page, set his country aflame and put it to the sword, cut fathers’ throats and seize their daughters to lend credit to this book, force men to choose between his religion and death (…) This is something for which mankind can never find excuse.”[18]

The indecisive stance between those in the 17th and 18th centuries who derived their impressions of Islam and the Prophet from Christian polemics, and those who reached their views through the testimony of many travelers and scholars to the greatness of Islamic civilization, led to the emergence of different kinds of studies on Islam. One of the most important works in this regard is Henry Stubbe’s The Defence of Islam. A typical Renaissance man, historian, librarian, theologian, and physician, Henry Stubbe (1632–1676) authored an unusual book titled: An account of the rise and progress of Mahometanism, with the life of Mahomet and a vindication of him and his religion from the calumnies of the Christians.[19] In fact, the Prideaux work mentioned above was written in direct response to Stubbe’s book. Swimming against the current, Stubbe showed no hesitation in refuting the traditional accusations of violence and lust commonly associated with Muslims. More importantly, Stubbe openly argued that Islam was the religion most in harmony with human reason and nature, thereby implicitly criticizing Christian theology and rituals. In a typical passage from his book we read:

“Here is the essence of the Muhammadan religion: on the one hand, it does not compel mankind to believe in many obscure concepts that are difficult to grasp and contrary to reason and common sense; on the other hand, it does not burden man with many difficult, costly, and superstitious rites, but instead recommends direct obedience, namely, religious worship, which is the surest way for mankind to fulfill its duty both to fellow humans and to God.”[20]

In addition to defending Islamic faith, Stubbe, who was the forerunner of a new class of European scholars who began to work on Islam in the 18th and 19th centuries, also made extremely fair statements about the Prophet.

Another significant exception of this period was the famous Swedish theologian and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772). According to Swedenborg’s historical theology of Islam’s rise, the spread of Islam was part of divine providence. In his view, the true purpose of Islam and its Prophet was to eradicate the idolatry that had dominated pre-Islamic Arab belief. Since the Church was too weak to combat idolatry, it had spread even in Arabia’s neighboring regions. God responded to this historical condition by sending a new religion. Concerning this religion, “suited to the genius of the Orientals,” Swedenborg said:

“The Muhammadan religion sees Jesus as the Son of God. He is the wisest of men and the greatest of the prophets. This religion was sent by God’s divine justice to eradicate the idolatry of many nations. (…) Idolatry had to be uprooted. In place of an idolatry doomed by God’s divine justice, a new religion had to arise. This new religion had to be planted in the genius of the East, include elements from both of God’s Covenants, and teach that God had come into the world. He was the wisest of men, the greatest of the prophets, and the Son of God. This plan was fulfilled through Muhammad.”[21]

Although Swedenborg believed that Muslims adhered to the doctrine of the Trinity, he explained why they accepted Jesus only as a prophet and not as a divine being:

“Orientals believe that God is the Creator of the universe, and they cannot comprehend that God came down to earth and took the place of mankind. In truth, it can hardly be said that Christians themselves understand this.”[22]

Combining the theology of history with the anthropology of the “East,” Swedenborg argued that Islam was in fact a religion carrying the same essential message as Christianity. Given the increasingly strident attacks against Islam from conservative Christians in recent decades, especially after September 11, the significance of Swedenborg’s mystical theology cannot be overstated. Together with Goethe, Swedenborg and others clearly demonstrated that Christians and Muslims could coexist peacefully, socially, and, more importantly, on religious and theological grounds.

In contrast to the vehement opposition of Pascal, Bayle, Prideaux, and Voltaire to Muhammad as a religious figure, Stubbe and some of his contemporaries argued that, setting aside the claim of divine revelation, the Prophet of Islam should be appreciated for his achievements in history, highlighting his qualities as a man of the world. This marked an important step away from the rigid Christian judgment of Muhammad as a false prophet toward an emphasis on his human qualities. It also signaled the beginning of a new approach in which Muhammad and other historical figures were described with secular terms like “heroes” and “geniuses”, explicitly employed by Enlightenment thinkers as counters to Christian historiography. The 17th and 18th centuries thus witnessed a growing number of scholars and intellectuals who adopted this outlook, taking more liberal and less hostile attitudes toward Muslims and Islam.

At Oxford, Edward Pococke (1604–1691), the first to hold a chair in Islamic studies, published Specimen Historiae Arabum, a work composed of various studies. He produced translations in Islamic history, discussed the basic beliefs and practices of Islam, and provided selections from al-Ghazālī’s works. By the standards of his time, Pococke’s work can be considered a major step in academic Islamic studies. He was also one of the first among European scholars of Islam to travel in the Muslim world in order to collect source materials. Equally famous and important was George Sale (1697–1736), who, instead of relying on Robert of Ketton’s 12th-century translation, based his 1734 English translation of the Qur’an on the Latin version[23] published in Padua in 1698 by Lodovico Marracci.

Sale had no intention of attributing any originality to Islam as a religion. He made this clear in the “Preface” he wrote as an introduction to his translation. Sale’s general approach to Islam, for which he was somewhat disparagingly called “semi-Muslim,” actually contributed to the streamlining of Islamic studies in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries and to the emergence of Orientalism as a discipline. Sale’s translation of the Qur’an contributed significantly to the earlier English translation prepared by Alexander Ross, based on the 1647 French translation of the Qur’an.[24] Like Sale’s, Ross’s edition also included a short section about Islam and its Prophet. In this part, Ross explained to his Christian readers the reason for his work’s existence and assured them that reading the Qur’an would never pose any danger to them. For, according to Ross, the Qur’an was “composed of contradictions, insults, obscene language, and absurd tales.”[25] It should be emphasized that Ross’s translation was the first Qur’an ever published in America. It was published in Massachusetts in 1806 and went through many editions before Sale’s translation became the standard text. Nonetheless, Sale’s version remained the most widely used English translation up until the late 19th century. Gibbon and Carlyle, who read Sale’s work, described the Qur’an as “a book of wearisome confusion, crude and inelegant, filled with endless repetitions, empty expressions, and tangled nonsense; in short, the most insupportable absurdities.” According to them, “No European can read the Qur’an from beginning to end unless driven by a sense of duty!”[26] While the Quran and some religious institutions of Islam, which are related to it, were constantly denied, the human characteristics of the Prophet of Islam were used by the humanist intellectuals of the 18th and 19th centuries either to direct cunning criticisms against Christianity or to uphold their own humanist-secular philosophy of history. The depiction of the Prophet Muhammad as a hero and genius, a man of remarkable intelligence and insight, endowed with persuasive power, dedication, and sincerity, reached its height in Carlyle and his philosophy of history based on the idea of heroism.

In his works, Carlyle described the Prophet as a truly remarkable man of world stature: a hero, a genius, a charismatic figure, someone whom the medieval Christian spirit could neither see nor appreciate. Although Carlyle conducted his analyses of the Prophet within a completely secular framework, thus completely excluding accusations of heresy, he felt compelled to apologize for expressing positive opinions about the Prophet:

“Since there is no danger that could happen to us, I can say all the good things I can about him. This is the only way to uncover his secrets: let us try to understand what he meant to the world; then it will be easier to understand what the world meant through him.”[27]

One of the more confident and outspoken voices of this period was Goethe (1749–1832). The famous German poet and thinker, while openly expressing his admiration for all things Islamic, neither concealed his praise nor adopted an apologetic tone. Goethe’s West-östlicher Divan (West-Eastern Divan) can be seen as a loud celebration of Islamic culture. It would not be right to describe Geothe’s interest in Islamic culture as a simple curiosity of a German poet, especially when one looks at the sentence he quotes from Carlyle: “If this is Islam, don’t we all live in Islam?”[28] Goethe’s 19th-century call resonated with an entire generation of European and American writers, particularly Emerson and Thoreau.[29]

[1]Inferno, Chapter 28. Here, Dante depicts heretics on the ninth level of Hell. Dante places the Prophet Muhammad in Hell, holding him responsible for divisiveness and the corruption of order. In this depiction, we see echoes of the label “Ismaili heresy” coined by St. John the Syrian and Bede in the 8th century for Islam.

[2]See Miguel Asin Palacios, Islam and the Divine Comedy (with summary by Harold Sunderland), London 1926, pp. 256-263.

[3]Lull’s very important work, Ars Magna, contains very rich examples for the approach that Islam is a religious and cultural/philosophical challenge.

[4]Averroists are known for their various heretical views, that attributed to Ibn Rushd and his Latin followers, all of which are listed in the 1277 condemnation list of Averroism. Four of these are particularly important: the eternity of the universe, the claim that God does not know particulars, monopsychism, the idea that a single intellect is shared by all humans and thus indirectly absolves them of moral responsibility, and finally, the famous theory of double truth, the idea that religion and philosophy have different conceptions of truth and must be clearly distinguished. The third view, related to Monopsychism, was seen as such a major challenge to Christian theology that St. Thomas Aquinas was compelled to write a work titled “On the Unity of the Intellect against the Averroists.” For the 219 allegations condemned by Bishop Tempier at the behest of Pope John XXI, see Philosophy in the Middle Ages: The Christian, Islamic, and Jewish Traditions, ed. Arthur Hyman-James J. Walsh, Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis 1973, pp. 584–591.

[5]De consideratione, III, I, 3-4 quoted by: Benjamin Z. Kedar, Crusade and Mission, p. 61.

[6]Oljaitu’s acceptance of the Shiite sect of Islam instead of Buddhism or Christianity, which he had previously researched, is a very serious event that has repercussions on Islamic history, Shiite, and Muslim-Christian relations. For some Christian responses to the historical Mongol conversion, see David Bundy, “The Syriac and Armenian Christian Responses to the Islamification of the Mongols,” in John Victor Tolan, ed., Medieval Christian Perceptions of Islam, Garland Publishing, New York-London 1996, pp. 33–53. See also Carl Brockelmann, History of the Islamic Peoples, Capricorn Books, New York 1960, pp. 250–252.

[7]Haskins attributes a significant role to the interactions between Muslims and Christians in Andalusia, and especially in Toledo, where translations from Arabic into Latin were the centre for the development of a completely new intellectual environment in the 12th century; see The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1976 (1st ed. 1927), pp. 278-367.

[8]Quoted from Alvaro, Indiculus luminosus, chapter 35: Grunebaum, Medieval Islam, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago-London 1946, p. 57.

[9]For a summary of the place of Andalusia in the history of Islam and the West, see Anwar Chejne, “The Role of al-Andalus in the Movements of Ideas Between Islam and the West,” in Khalil I. Semaan, ed., Islam and the Medieval West: Aspects of Intercultural Relations, State University of New York Press, Albany 1980, pp. 110–133. See also Jane Smith, “Islam and Christendom,” in The Oxford History of Islam, ed., J.L. Esposito, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999, pp. 317–321.

[10]Luce Lopez-Baralt, The Sufi Trobar Clus and Spanish Mysticism: A Shared Symbolism, Iqbal Academy, Lahore 2000.

[11]Les Pensées de Blaise Pascal, Le club français du livre, 1957, pp. 200-201.

[12]Relation of a Journey began An. Dom. 1610, p. 60 Quoted by Jonathan Haynes, The Humanist as Traveler: George Sandys’s Relation of a Journey Began An. Dom. 1610, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, London Toronto 1986, p. 71.

[13]Sandys, op. cit., pp. 59-60, quoted in Haynes, op. cit., p. 70.

[14]The Dictionary Historical and Critical of Mr. Peter Bayle, Garland Publishing, Inc., New York-London 1984, vol. IV, p. 29.

[15]Bayle, The Dictionary, pp. 30 and 47.

[16]Bayle, The Dictionary, p. 39.

[17]For Prideaux’s approach to Islamic history, see P.M. Holt, “The Treatment of Arab history by Prideaux, Oackley and Sale,” ed. B. Lewis P.M. Holt, Historians of the Middle East, Oxford University Press, London 1962, pp. 290-302.

[18]Quoted from Lettre au roi de Prusse: N. Daniel, Islam and the West, p. 311.

[19]Stubbe’s book remained in manuscript until it was first prepared and published by Hafiz Mahmud Khan Shairani (Luzac, London) in 1911. The second edition was published in Lahore in 1954. For references to Stubbe’s work, see P.M. Holt, A Seventeenth-Century Defender of Islam: Henry Stubbe (1632-1676) and His Book, Dr. Williams’s Trust, 1972.

[20] Quoted by: Holt, A Seventeenth-Century Defender of Islam, pp. 22-23.

[21]E. Swedenborg, “Divine Providence”, A Compendium of Swedenborg’s Theological Writings, ed. Samuel M. Warren, Swedenborg Foundation, Inc., New York 1974, pp. 520-521.

[22]Swedenborg, op. cit., p. 521.

[23]In addition to his meticulous translation of the Qur’an into Latin in the late 17th century, Maracci also wrote several polemical works against Islam. Two of these, Prodromus and Refutatio, were included in his translation; cf. N. Daniel, Islam and the West, 321.

[24]Other translations of the Qur’an into European languages were made in the 18th and 19th centuries. Works by Claude Etienne Savary (1750–1788), Garcin de Tassy (1794–1878), and Albert de Biberstein Kasimirski (1808–1887) include partial translations of the Qur’an into French. Although anonymous translations of the Qur’an into English were readily available in England in the 19th century, Sale’s translation remained the most accepted text. We know that Martin Luther (1483-1546) was interested in the Qur’an in Germany. In this context, it has even been claimed that Luther himself made a selection of translations from the Qur’an. In 1659, Johann Andreas Endter and Wolfgang Endter published a German translation of the Quran under the title al-Koranum Mahumedanum. In a fashion of the late Middle Ages, the Qur’an was called “the holy book of the Turks” and sometimes “the Turkish Bible.” This was followed by Johan Lange’s version published in Hamburg in 1688. Theodor Arnold’s Der Koran, based on the Arabic original and Sale’s English translation, was published in 1746. This was followed by David Friedrich Megerlin’s Die Turkische Bibel order des Koran (1772). A comprehensive list of Qur’an translations can be found in the World Bibliography of Translations of the Meanings of the Holy Qur’an: Printed Translations, 1515-1980 (Research Centre for Islamic History, Art, and Culture [IRCICA], Istanbul 1986), edited by İsmet Binark and Halit Eren and published with an introduction by Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu. See also Muhammed Hamidullah (trans.), Le Saint Coran, Club Francais du Livre, Paris 1985, pp. LX-XC.

[25]Quoted by Fuad Sha’ban, Islam and Arabs in Early American Thought, p. 31.

[26] Thomas Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History (1840), ed. Carl Niemeyer, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln-London 1966, pp. 64-65. Carlyle calls Sale’s translation “a very accurate translation.”

[27]Carlyle, op. cit., p. 43.

[28] Carlyle, op. cit., p. 56.

[29] John D. Yohannan, Persian Poetry in England and America: A 200-Year History, Caravan Books, Delmar, N.Y. 1977.