Why are low- and lower-middle-income countries’ (LLMICs) external borrowing costs so high? The issue has featured prominently in global debates this year. The Sevilla Commitment (the outcome of the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development in June) and the Jubilee Report (commissioned by the late Pope Francis) outlined common principles for tackling the problem. The question now is whether South Africa’s G20 presidency can translate those principles into practical agreements.

The issue is urgent because official aid is projected to fall sharply in 2025-26. Not only has the United States shut down the US Agency for International Development, the world’s largest bilateral donor, but several European countries have also slashed their own aid budgets. Moreover, these moves come on the heels of a sharp tightening in traditional capital markets. Since 2022, developing countries have lost access to commercial finance, making it exorbitantly costly – or simply impossible – to refinance maturing debt.

The Sevilla Commitment and Jubilee Report recommended expanding development banks, increasing access to private capital flows, enforcing fairer rules for foreign investment, strengthening the global financial safety net, and introducing global taxes to finance global public goods. They also called for a more straightforward approach (echoing our own Bridge Proposal) to common “gray zone” situations, where external debts are not high enough to make a country insolvent but are large enough to squeeze out development spending.

In practice, this would mean implementing the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s proposed “3-pillar approach,” which recommends: domestic efforts to raise more revenue; increased official financing for countries that make determined structural-adjustment efforts in order to grow out of debt; and, crucially, reducing debt servicing to commercial creditors during the adjustment period.

Not so long ago, the first recommendation would have seemed unrealistic. But experts from developing countries have increasingly recognized the need for tax increases, spending cuts, or some combination of the two. Many acknowledge the promise of the Côte d’Ivoire model, whereby successful reforms reduce market spreads and help to bring debt-servicing burdens back to manageable levels. But such reforms need to be carefully prepared. Raising taxes or cutting expenditures too quickly can lead to destabilizing, violent protests, as we recently saw in Kenya. When that happens, market risks end up even more elevated.

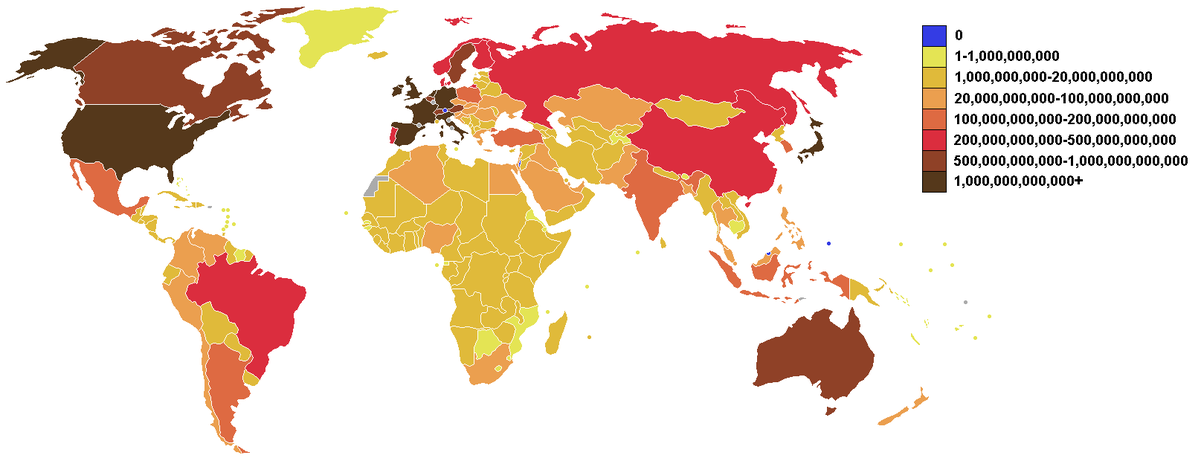

The second pillar concerns financing, which is necessary to drive any growth recovery. Unfortunately, the pandemic-era surge in counter-cyclical lending by the IMF, the World Bank, and regional development banks has receded. By 2023, net transfers by these institutions and the Paris Club of sovereign creditors to LLMICs had already fallen to around $30 billion – less than half the $70 billion in 2020 – and the IMF’s own net transfer had turned negative. With financing drying up, scaling up these institutions’ financial capacity, whether with special drawing rights (the IMF’s reserve asset) or new capital, has become an urgent priority.

The third pillar – reducing debt servicing to commercial creditors – is necessary for the other two pillars to stand. Net transfers to LLMICs in 2025 are projected to be negative for the fifth consecutive year, owing to large private capital withdrawals. If resources from international financial institutions (IFIs) continue to go toward repaying commercial creditors rather than toward domestic investments, the likelihood of sovereign default will rise.

The core problem is the cost of borrowing, which is too high to allow debtor countries to refinance their commercial debts. While the IMF assumes, perhaps optimistically, that markets can regulate themselves, spreads for poorer LLMICs remain elevated (the median rose from 200 basis points in 2018 to 700 bps in 2025), even as those for upper-middle-income countries have normalized.

As the Sevilla Commitment recognizes, without concerted efforts to prevent capital outflows, developing countries cannot grow out of debt. In fact, IFIs are becoming part of the problem. Our recent research finds that a large share of IFI debt ultimately raises the cost of financing from the private sector. Because IFI loans enjoy de facto senior status, they reduce the recovery value for other creditors in cases of distress, prompting those investors to charge more for new loans. Thus, IFI lending has an underappreciated opportunity cost. If it does not help countries grow out of debt, it ends up making things worse by increasing their overall borrowing costs.

The share of LLMICs’ external debt owed to IFIs has grown from a median of 35% in 2018 to 45% in 2023. Worse, there are around 20 countries where this share exceeds 75%, and 56 where it exceeds 50%. As inadequate IFI support finances bailouts for creditors instead of fostering recoveries for these economies, it is creating a lethal debt spiral that threatens not just debtor countries, but also the IFIs’ own balance sheets.

Addressing this leakage of funds to private lenders requires a concerted effort to improve transparency and cooperation among all creditors. Supporting illiquid developing countries’ voluntary return to the market is necessary for some. In many other cases, however, a negotiated rescheduling is also needed. Admittedly, this is a tall order, given the stigma attached to debt restructuring. That is why we need clear rules, rather than discretion. The IMF already has tools to force a rescheduling when needed, such as by lending into arrears. While such tools are generally reserved for countries in debt distress, they could also be applied to gray-zone cases.

A rule to ensure discipline and proper burden-sharing might resemble the legal scholar Sean Hagan’s proposal to limit IMF exceptional-access lending by establishing a hard limit on all inflexible (senior) debt for countries facing gray-zone conditions. For example, when inflexible debt reaches 60-65%, a Fund program would automatically require that commercial debts be rescheduled, thus ensuring that sufficient funds remain in the debtor country to support a growth recovery.

Since the South Africa G20 will be followed by France’s hosting of the G7, there is a unique opportunity to form a coalition of the willing that would include most G7 member states and China. But if South Africa cannot broker cooperation between the Global North and South, the opportunity to resolve today’s debt crisis may be lost for a generation. This might be our last chance to prevent a debt disaster that would halt progress on development and climate-change mitigation, as well as jeopardize the Bretton Woods system itself.

Ishac Diwan is Research Director at the Finance for Development Lab and Professor of Economics at the American University of Beirut.

Vera Songwe is a nonresident senior fellow in the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution, is Co-Chair of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance.