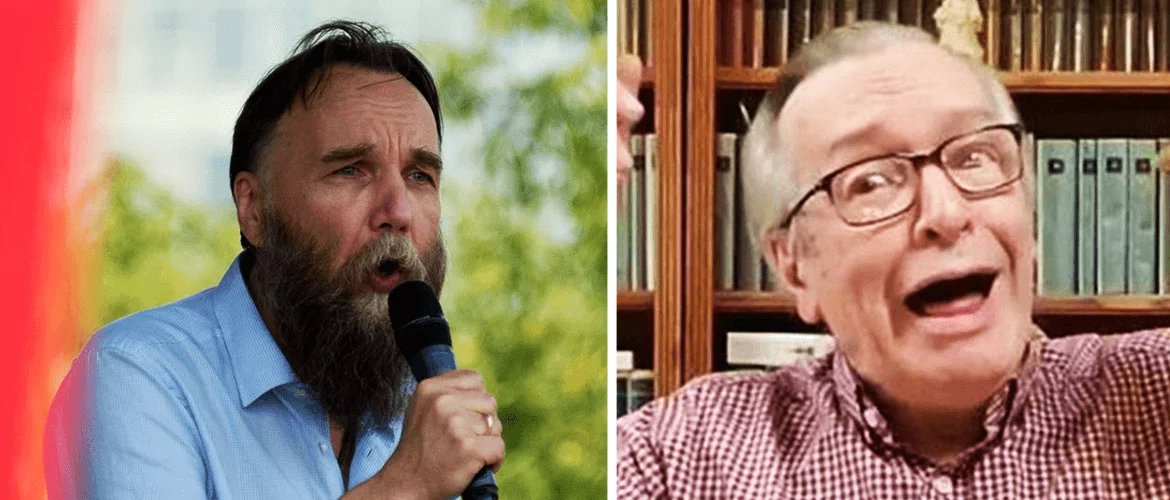

Olavo de Carvalho and Aleksandr Dugin attack liberalism from opposite corners.

In an era that fetishizes credentials—PhDs, think-tank affiliations, the alphabet soup of academic merit—it is striking that two of the most influential political philosophers of the early twenty-first century earned their standing without any of them. Neither Olavo de Carvalho, the Brazilian autodidact who settled in Virginia, nor Aleksandr Dugin, the Russian mystic of geopolitics, came by influence through scholarly peer review. Instead, both clawed their way into the imagination of presidents and movements by acting less like university professors and more like prophets at court.

They are the kinds of figures who offer a reminder that political ideas, however baroque or marginal they may seem, can migrate from blog posts or self-published books to the presidential palace and, in the process, reconfigure entire nations. Their stories, which converge and then sharply diverge, reveal how multipolarism—the mantra of a “post-Western” world—became less an ideology than an alibi, a placeholder for energies that could not be reconciled into a shared project.

Their proximity to power was not an academic matter: it produced tragedies that claimed lives, including their own families.

The Virginia Prophet

Imagine a prophet in exile, seated not in Athens or Jerusalem but in Richmond, Virginia, chain-smoking and livestreaming into Brazilian bedrooms. That was Olavo de Carvalho, who began life as a journalist and astrologer, dabbled in philosophy without a degree, and eventually became the intellectual godfather of Brazil’s populist right.

Through a blizzard of YouTube lectures, blog posts, and polemical books, Carvalho peddled a worldview of relentless cultural struggle. The Cold War, he insisted, had never ended; communism had simply put on new clothes. “Cultural Marxism” was his refrain, a totalizing explanation for everything from academic feminism to public health campaigns. His rhetorical gift was less in the nuance of arguments than in the heat of denunciation. He spoke like a man who had just stumbled onto a conspiracy too vast to ignore and too dangerous to keep to himself.

By the 2010s, his books were on the bedside tables of Brazilian politicians, including Jair Bolsonaro. Carvalho never held office, but his fingerprints were all over Bolsonaro’s discourse. He provided the intellectual permission slip for conspiratorial anti-globalism in Brasília. It was no coincidence that Bolsonaro’s movement invoked Carvalho as a guru, and that Carvalho’s online school trained cadres of new-right influencers.

Carvalho’s vision of multipolarism was instrumental. He saw Brazil as part of the West—Christian, anti-communist, aligned with the United States. His quarrel was not with unipolarity itself but with the specter of global governance by elites. Multipolarism, in his usage, was a rhetorical cudgel, not a philosophy: a way to say no to supranational institutions and leftist internationalism without necessarily offering a coherent geopolitical alternative.

But rhetoric has consequences. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Carvalho ridiculed masks and vaccines, calling the crisis a hoax designed to enslave populations. His followers in government took note, and Bolsonaro made pandemic denialism a matter of state. Carvalho himself contracted COVID and died in January 2022. His family said the virus was the cause, while his doctor listed emphysema, pneumonia, and other factors. The symbolism was cruelly apt: a prophet slain by the very plague he had denied.

The Geopolitical Mystic

If Carvalho was a cranky neighbor broadcasting from the suburbs, Aleksandr Dugin has always played the part of a mystic. Bearded, robed, photographed in snowy landscapes, he cultivated the air of a man communing with history itself. His influences were esoteric: René Guénon, Julius Evola, Martin Heidegger. His first reputation in Russia was as a dissident occultist; later, he emerged as a political theorist of civilizational destiny.

At the core of Dugin’s thought is the “Fourth Political Theory.” Liberalism, communism, and fascism, he argues, are exhausted. The task is to forge a new ideology rooted in traditionalism, spirituality, and cultural pluralism. For Russia, that means rejecting the “Atlanticist” West and leading a Eurasian civilizational bloc stretching from Dublin to Vladivostok. Multipolarism, in Dugin’s telling, is not a diplomatic arrangement but a metaphysical law. At a Multipolarity Forum in February 2024, he declared: “The multipolar world is primarily a philosophy. The West is not all of humanity…”

Dugin’s relationship to the Kremlin is complicated. Arguing over his direct influence on Vladimir Putin misses the point—Dugin’s work was institutionalized across Russia years before Putin came power. His ideas have resonated since the 1990s in the ideological atmosphere of Russian politics, surfacing in speeches and strategies. Where Carvalho was a political arsonist throwing rhetorical firebombs, Dugin has been more like incense: diffuse, symbolic, but intoxicating.

Fame and influence also brought Dugin personal losses. In August 2022, his daughter, Darya Dugina, a pro-war commentator, was killed in a car explosion outside Moscow. Russian authorities blamed Ukrainian agents; Kyiv denied involvement, and the truth remains contested. The image of the grieving philosopher at his daughter’s funeral was a chilling reminder that his ideological battlefield was not metaphorical.

A Debate that Failed

It is tempting to imagine Carvalho and Dugin as natural allies—both anti-liberal prophets, both thorns in the side of cosmopolitan elites. In 2011, they even held a written debate, The USA and the New World Order. For Dugin, the exchange was part of his wider attempt to stitch together a transnational league of conservative intellectuals, united by opposition to the West. For Carvalho, however, the conversation was a chance to draw a bright red line.

Carvalho denounced Eurasianism as a Trojan horse. In his eyes, Russia could never be the savior of Christianity or tradition; it was itself captive to authoritarianism and false mysticism. He saw in Dugin not an ally but a rival prophet peddling counterfeit revelations. Dugin, in turn, dismissed Carvalho as a provincial agent of U.S. influence, a mouthpiece for Washington’s hegemony disguised as philosophy.

What emerges from their failed dialogue is that multipolarism can accommodate diametrically opposed visions—Brazil as guardian of the West, Russia as heir to Eurasia—but, at least so far, cannot reconcile them. It unites only in opposition to something else, usually “the liberal order.” As soon as positive visions are required, the alliance collapses.

Philosophy at Court

Both men illustrate what happens when philosophers, or something like them, hover near power. They were cultural intermediaries, translating metaphysical anxieties into political slogans. They were not system-builders in the academic sense; they were indexers of energies, voices that gave form to fears their societies already harbored.

In Carvalho’s case, the danger was epistemic: deny reality long enough, and reality bites back. In Dugin’s, the danger was existential: glorify war and civilizational struggle, and violence can come home. Their proximity to power underscores the banality of philosophy when weaponized. Ideas once confined to eccentric tracts became slogans in presidential campaigns, talking points in parliaments, and, eventually, reasons to risk lives. The philosopher at court is not an ornament but a hazard, a reminder that ideas, however strange, can kill.

Olavo de Carvalho and Aleksandr Dugin are unlikely heirs to Plato’s philosopher-king. Yet in a century that prizes technocracy and credentialism, their rise tells us something sobering. Influence is not a meritocracy of degrees; it is a market for passion, prophecy, and polemic.

Both men are prophets of multipolarism. Both rejected the liberal order. Yet their stories refuse to merge into a shared narrative. Carvalho wanted Brazil to defend the West; Dugin wants Russia to bury it. Carvalho died after denying the plague; Dugin buried his daughter, collateral damage from the war he celebrated.

They both serve as a stark reminder that ideas do not stay in books. Ideas migrate, adapt, and sometimes explode. And when philosophers leave the library and enter the court, their words are no longer just theory: they are wagers with history.

* Byron Byrne-Taylor is a lecturer of English and Translation at Shanghai International Studies University.

Source: https://fpif.org/court-philosophers-in-the-age-of-multipolarism/