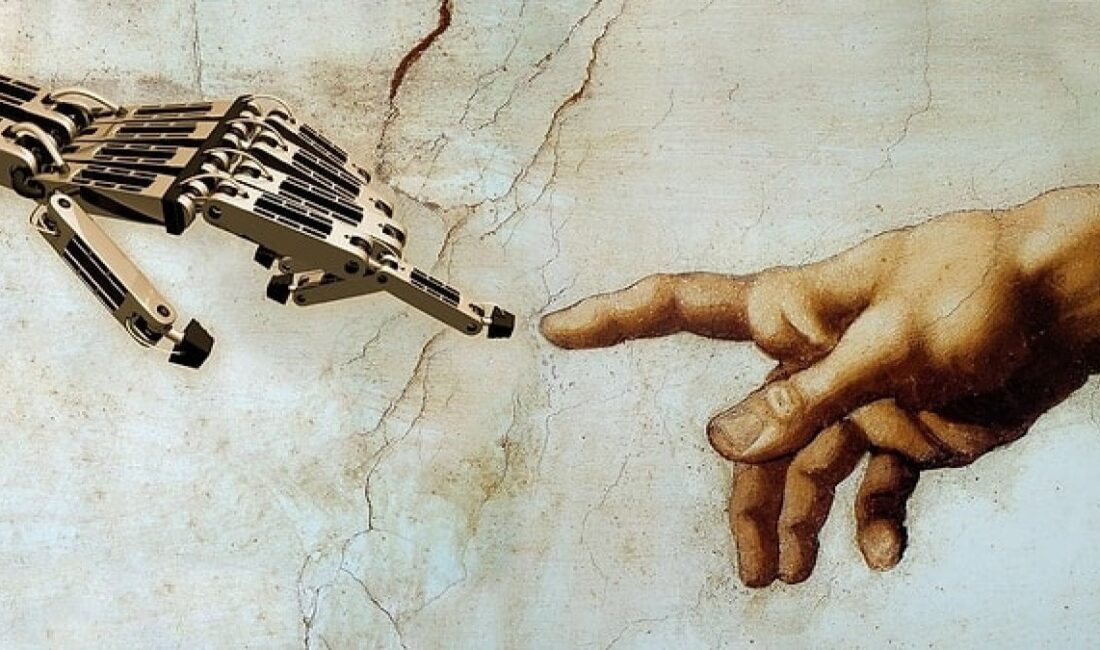

AI, Human Uniqueness, and Public Policy:

s the EU AI Act enters force and U.S. agencies implement OMB Memorandum M-24-10, a defining question of the digital age emerges: what makes humans irreplaceable in law and governance? Policymakers rightly focus on fairness, transparency, and risk, but the deeper issue runs beneath the code—how to preserve the moral boundary between creators and their creations. My argument is simple: we cannot sustain democracy’s moral architecture if we forget the theological foundation underpinning it.

The biblical claim that humanity is made as the imago Dei—the image of God—is not merely a sectarian doctrine; it is the most stable philosophical anchor for human dignity ever articulated. Unlike modern accounts that tie worth to cognitive capacity or rational self-awareness, the Genesis framework grounds dignity in status rather than ability. The Hebrew grammar of Genesis 1:26-28—bĕtselem ʾĕlōhîm—conveys not that humans are made in God’s image but as His image, a predicative construction (the beth essentiae) signifying vocation, representation, and delegated moral authority.

This means that every human being—infant, elder, disabled, or ordinary—is a bearer of divine responsibility. We are not dignified because of what we can do, but because of whom we represent. The theological implication becomes a civic one: if human value rests on divine commission rather than variable capacity, then no artifact, however intelligent, can share our moral status.

Policy circles often shy from theology, fearing sectarian import. Yet grounding human uniqueness in the imago Dei strengthens, rather than undermines, pluralist legitimacy. As philosophers Nicholas Wolterstorff and Miroslav Volf note, biblical anthropology supplies the metaphysical foundation that secular humanism has long sought—a rationale for equality that survives both automation and ideology. When rights depend on divine image rather than neural sophistication, personhood ceases to be a moving target.

This matters urgently now. Across legislatures, proposals for “AI personhood” are resurfacing. In 2017 the European Parliament even floated “electronic personhood” for autonomous systems. Such gestures may appear symbolic, but their jurisprudential effect would be seismic. If machines are recognized as legal persons, accountability dissolves into code. Who answers when an algorithm discriminates, misfires, or kills? To preserve democratic coherence, responsibility must remain with those capable of moral agency.

That is why the first pillar of any responsible AI regime must be a legal prohibition on AI personhood. This is not a theological imposition; it is a safeguard for the rule of law. As legal scholar Ryan Calo warned, assigning personhood to artifacts risks “accountability off-loading”—a bureaucratic shell game in which blame disappears into silicon proxies. Law must affirm, explicitly, that only humans bear culpability because only humans can choose.

The second imperative is to move from “human-in-the-loop” to Human-in-Responsibility (HIR). The difference is subtle yet decisive. “Human-in-the-loop” means procedural involvement—a button pressed, a checkbox ticked. HIR means that for every consequential AI decision in health, justice, finance, or defense, a named individual is legally accountable. The analogy is Sarbanes-Oxley: just as CEOs must certify their companies’ financial statements, executives or officers should certify AI outputs that affect life, liberty, or livelihood. In healthcare, a licensed physician must sign off on an AI-assisted diagnosis; in defense, commanders must authorize automated targeting decisions under Directive 3000.09. Responsibility thus becomes not a symbolic principle but an enforceable compliance requirement.

The third reform is to mandate Dignity Impact Assessments (DIAs) alongside technical risk reviews in government procurement. Building on the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) AI Risk Management Framework and Whittlestone et al.’s ethics-in-practice research, DIAs would evaluate whether an AI system risks treating humans as replaceable, surveilled, or subordinated. They would ask: does this deployment erode deliberative autonomy, coerce consent, or deskill the professions through which vocation is exercised? The answers would map directly onto existing NIST controls—transforming biblical anthropology into auditable policy infrastructure.

Fourth, governments should adopt Dignity-by-Design procurement standards. Every public AI contract should require demonstrable safeguards for contestability, explanation, and human fallback authority—benchmarked against the AI Bill of Rights, OECD, and UNESCO principles. These are not abstract virtues; they are engineering constraints that keep the moral center of gravity with persons. When developers know that accountability cannot be delegated to algorithms, they design differently: transparency becomes an architectural parameter, not a press-release promise.

These measures are mutually reinforcing. Together they create what might be called the “governance moat” for AI—rules that encode humility into the system. They also operationalize what the Bible describes as stewardship: dominion bounded by duty, creativity checked by conscience. Far from hindering innovation, such frameworks build trust. Just as environmental law preserved industrial legitimacy, dignity law can preserve digital legitimacy.

Skeptics will say this smuggles religion into policy. Yet the claim here is not confessional but constitutional. The imago Dei translates seamlessly into secular equivalents: intrinsic dignity, equal protection, non-substitutability. It harmonizes with Kantian ethics, with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and with the equal-protection clauses of democratic charters. Its power lies in providing an ontological justification for why these civic norms exist at all. In plural societies, policies endure when they rest on sources of legitimacy recognized across faith and non-faith publics.

We stand at a hinge moment. The Biden Administration’s OMB M-24-10 requires every federal agency to implement AI risk-management frameworks, while the EU’s 2024 AI Act begins phased enforcement. At stake is more than compliance; it is anthropology. Will governments encode a view of the human as accountable steward—or as an upgradeable node? The biblical vision of human-in-responsibility offers foresight, not nostalgia. It ensures that as our machines grow capable, our moral order does not collapse into their logic.

In truth, democracy’s survival depends on precisely this anthropology. A polity that confuses capacity with worth will soon grant rights to the efficient and deny them to the weak. By anchoring dignity in divine image, we retain a concept of personhood resilient to both technological imitation and ideological drift. The imago Dei is therefore not a relic of pre-modern thought but a civic design principle—a reminder that progress untethered from moral ontology degenerates into automation without accountability.

AI may outthink us, but it can never out-image us. Only humans—fragile, fallible, yet entrusted—bear responsibility for shaping a just technological future. Law must protect that difference. Policy must be built on what cannot be automated: human dignity, accountability, and responsibility. The age of machines demands not less theology, but better anthropology.

* Emir J. Phillips, JD/MBA/DBA, is an associate professor of finance at Lincoln University and a longtime financial advisor. His teaching and research focus on political economy, banking, and the moral foundations of markets. His scholarship has appeared in the Journal of Economic Issues and the Cambridge Journal of Economics. He writes for Providence on Christian public policy and economic statecraft, drawing on academic and practitioner experience in finance.