Over the past 15 years, Türkiye has not only updated its understanding of security but has also undergone a profound architectural transformation in how security is produced. This transformation is observed not in reactions to individual threats, but rather in how the state positions itself. The security architecture being discussed today goes beyond military capacity; it refers to a multi-layered structure in which intelligence, diplomacy, technology, and political decision-making processes are deeply intertwined. Therefore, it is useful to assess this new situation through the lenses of paradigm shift, institutional integration, regional and global vulnerabilities, political continuity, and social and economic dimensions.

Security Paradigm Transformation

Türkiye’s understanding of security long retained a reactive character. Threats would emerge either at the border or within the country, and the state would respond accordingly. In recent years, however, this understanding has given way to a proactive and preventive paradigm. Intervening in the geography where the threat arises, forming a transnational security belt, and effectively eliminating the distinction between internal and external security have become the core components of this transformation. In this context, security is no longer merely a military issue; it is approached as a domain where political stability, diplomatic maneuvering, and technological capacity intersect. Although the new paradigm is often discussed rhetorically through specific equipment, the true shift is not in tools, but in doctrine.

One of the most prominent features of the new security architecture is the increased level of institutional integration. This has become particularly visible in the emerging coordination among foreign policy, military structures, and intelligence. In this regard, the positioning of intelligence not merely as a collector of information but as a game-changing actor both in the field and in diplomacy is of critical importance. This new form of intelligence adds both momentum and depth to foreign policy and military postures. Foreign policy itself has moved beyond normative discourse and is now shaped by geopolitical reflexes such as crisis management, balancing, and mediation. This indicates that foreign policy has acquired a more pragmatic and field-oriented character. While the military structure constitutes the operational power of this triad, decision-making processes have become more centralized and accelerated. Additionally, the increased use of local resources and domestic technology stands out as another key achievement of the security architecture under discussion. It is evident that the integration we describe has produced effectiveness. Nevertheless, ensuring adequate sensitivity regarding institutional oversight and transparency remains crucial for the institutionalization of the new security architecture.

Do Political Changes Affect the New Architecture?

Although security policies in Türkiye are often associated with the ruling governments, security architectures typically outlast political periods. This is because such architectures are not merely the result of political preferences, but also stem from institutional capacity, tradition, and experience gained in the field. The core of the current architecture—the transnational security approach, the central role of intelligence, and multi-directional diplomacy—has largely become institutionalized. Therefore, potential political changes are more likely to influence how the security architecture is operated rather than whether it exists at all. In other words, orientation, rhetoric, and prioritization may shift. Certain areas may witness steps toward softening or normalization, but a complete abandonment of the architecture appears unlikely, considering both regional security dynamics and the current level of state capacity.

The key factor here is the extent to which the security architecture has crossed an irreversible institutional threshold. This is because elements such as cross-border military presence, intelligence networks, and defense industry infrastructure are not structures that can be dismantled quickly through political decisions alone. The real area of change lies in how security is defined, how it is legitimized, and within what democratic framework it is established. The openness of security policies to parliamentary oversight, their legal boundaries, and their social narrative can all be reconfigured according to different political preferences. This allows for the transformation not of the architecture’s hard core, but of its civil-democratic shell. In this context, the critical question is not whether the security architecture will persist, but with what political rationale and what democratic balance it will be sustained.

Regional Fragilities and the Security Architecture

The chronic instability of the Middle East, the presence of non-state armed actors, and the porous nature of borders compel Türkiye to establish a flexible, multi-layered, and situational security architecture rather than a fixed and static security doctrine. In this context, security is being redefined not merely as border defense but as the capacity for crisis management, area control, and the prevention of risk diffusion.

As seen in the cases of Syria and Iraq—where authority vacuums, despite some recent improvement, have taken on a structural rather than temporary character—hybrid and asymmetric risks have become permanent alongside traditional inter-state threats. Türkiye’s cross-border presence and intelligence-centered security approach constitute strategic responses to this permanence. Tensions revolving around energy competition and maritime jurisdiction in the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as the fragile balance in the Caucasus, require the security architecture to be approached not only from the perspective of the southern borders but through a multi-front lens. This expands the geographical scope of the architecture while simultaneously generating new zones of tension regarding resource allocation and prioritization.

The new security architecture should be seen not as the cause of regional instability, but rather as a response to its long-term and structural nature. However, the risk remains that this response may evolve into a constant and intense security reflex, thereby blurring the line between the temporary and the permanent. While the flexibility of the architecture is a clear advantage, whether that flexibility transforms into a permanent state of exception will be one of the most critical issues of debate in the coming period.

Global System: Multipolarity and Uncertainty

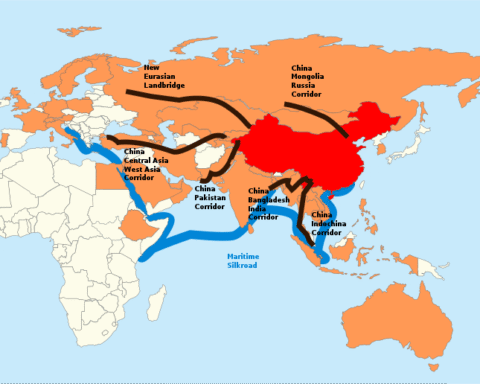

The US–China rivalry, NATO’s transformation, and increasing uncertainty in the global system all point to a departure from the long-standing normative and rules-based structure of the international order. In this environment, where power balances have become more fluid, geopolitical maneuvering space is expanding for middle-sized states, while predictability is significantly diminishing. Türkiye, in this setting, does not rely on a single strategic axis but instead pursues a multi-directional, flexible security and foreign policy course. Its approach of maintaining institutional ties with the Western alliance while simultaneously developing relations with Russia, China, and regional actors reflects this orientation. This stance clearly provides short-term tactical flexibility. However, it is worth considering the potential costs of managing such a strategy.

NATO’s shift from a collective security framework toward a structure in which national priorities are more decisive has rendered Ankara’s position within the alliance both more indispensable and more problematic. The core of this problem lies in the alliance’s reluctance to accept Ankara’s priorities. At times, tensions arise in the form of “my threat is not the same as yours.” Similarly, the global rise in sanctions policies, disruptions in supply chains, and energy security issues are reshaping security policies through economic and technological dependencies. In this regard, multipolarity represents not only a space of opportunity for Türkiye but also produces a regime of fragility that demands constant balancing. The sustainability of this flexibility depends not only on diplomatic skill but also on economic capacity, institutional stability, and internal political coherence. Otherwise, multi-directionality may result not in strategic autonomy but in the risk of strategic overextension.

Security Architecture, Economy, and Social Structure

The economy and social structure are often perceived as secondary, yet they are decisive. A security architecture is sustainable only insofar as it aligns with economic capacity and is supported by social legitimacy. Cross-border operations, the expansion of intelligence capabilities, and increased diplomatic engagement inevitably generate a significant economic burden. While these costs may appear manageable in the short term, in the long term, if a healthy balance is not established between security and development, the architecture risks reaching its own structural limits.

Security, of course, is not a substitute for economic capacity. However, it must operate in coordination with it. In an environment where economic fragilities are deepening, detaching security policies from cost-effectiveness analysis can weaken the claim to strategic autonomy. Therefore, the success of the security architecture should be measured not only by its operational capacity on the ground, but also by its economic resilience. On the other hand, security architectures are not sustained solely by state institutions. Social legitimacy is just as crucial as institutional capacity. In Türkiye, society has strong reflexes against security threats, shaped by historical and geographical conditions. However, when security is constantly presented as a state of exception, the perception of security may normalize over time, potentially leading to societal desensitization.

The internalization of this architecture by society is not achieved through the absolutization of security, but through transparency, accountability, and the maintenance of open channels for public debate. Otherwise, the discourse of security risks becoming a tool for passive acceptance rather than a framework for generating social consensus. While this may seem to ensure short-term stability, it carries the long-term risk of weakening the societal foundations of the security architecture. Therefore, discussions around the new security architecture should not merely focus on “how much security,” but rather on what economic and social costs are involved, and on what basis of political legitimacy security is being produced.

The Security–Freedom Balance

The balance between security and freedom is not an issue unique to Türkiye. However, this tension is experienced more acutely due to the country’s geographical position, regional instability, and historical state–society relations. In an environment where security threats have become continuous, the progressive expansion of the security sphere and the corresponding contraction of the sphere of freedom risks evolving from a temporary exception into a permanent mode of governance. The fundamental issue here is whether security is treated as a necessary public need or as a central principle governing the political realm. When security is positioned as an alternative to freedoms, legal boundaries become flexible, extraordinary measures become normalized, and democratic oversight mechanisms weaken. Although this may appear to generate stability in the short term, in the long run, it creates a paradox that erodes both freedoms and security itself.

The core question, then, is whether a political and legal framework can be established that defines security not as the opposite of freedom, but as its guarantor. The success of such a framework depends not only on legal regulations, but also on the transparency of security policies, openness to judicial review, and the functionality of parliamentary oversight mechanisms. Otherwise, the security discourse ceases to be a tool for generating democratic legitimacy and instead becomes a practice that narrows the space for governance in the name of control. For Türkiye, the path to removing this balance as a chronic issue lies in treating security not as an ever-expanding field, but as a public policy with clearly defined boundaries and subject to democratic oversight.

Continuity or Rethinking?

Türkiye’s new security architecture has been largely established and is not expected to disappear in the short term. Given regional fragilities and global uncertainties, this architecture is not merely a policy preference but a structural necessity. The current level of state capacity further reinforces this necessity. However, this observation should not imply that the architecture is fixed and beyond debate. The real issue lies in how this security architecture will be managed, within what political and legal boundaries it will operate, and what kind of relationship it will establish with society. As the scope of security expands, so too does the risk of decision-making processes becoming more centralized and exceptional measures becoming permanent. Therefore, the debate should not revolve around the necessity of security, but rather around the principles, oversight mechanisms, and societal consensus on which it will be sustained.

In the period ahead, two primary tendencies await Türkiye. The first is the continuation of the current security architecture, largely preserved, with further institutionalization and increased technical capacity. The second is to retain the core of the architecture while opening it up to reconsideration in terms of democratic oversight, economic sustainability, and social legitimacy. The difference between these two paths will not determine whether the architecture exists, but what quality it embodies.

Thus, rethinking should not—and does not—mean abandoning security. On the contrary, it reflects an approach that aims to make security more predictable, clearly defined, and accountable. The tension between continuity and rethinking should not be seen as weakening the architecture, but rather as an opportunity to make it more resilient if managed properly. Ultimately, the critical question is not whether the security architecture will persist, but with what political rationale, what economic capacity, and what social consent it will be sustained. The answer to this question will also offer insight into the kind of state and society we envision for the future.

Source: perspektifonline.com