The geopolitics of multipolarity: How to counter Europe’s waning relevance in Southeast Asia

It is perhaps trite but still true: the Indo-Pacific is rapidly emerging as the world’s geopolitical and economic centre of gravity. In 2025, Malaysia assumes the chairmanship of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), placing it at the heart of regional dynamics and offering a case study in how the region balances competing priorities. As it navigates its own ambitions – including a potential bid to join the BRICS+ – it must also contend with ongoing regional crises such as the turmoil in Myanmar/Burma and escalating tensions in the South China Sea.

These shifting currents should serve as a wake-up call for Europe. The region is becoming increasingly multipolar, with countries in the Indo-Pacific actively recalibrating their alliances. Yet, Europe risks being left behind, constrained by fragmented strategies and insufficient engagement. This decline is not just a matter of perception. Europe’s muted response to global crises, most notably the war in Gaza (1), has weakened its standing as a credible global player. Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar’s pointed remark – ‘Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems, but the world’s problems aren’t Europe’s problems’ (2)– captures a growing sentiment across the Indo-Pacific. Complacency is not an option. Europe’s economic and security future is deeply tied to the Indo-Pacific, which hosts critical supply chains, key shipping routes, and resources (3) essential for Europe’s green transition. The region dominates the production of semiconductors, rare earths and emerging technologies – sectors in which Europe remains heavily dependent. If Europe fails to recalibrate its approach, it will not only lose influence but also jeopardise the economic resilience and strategic autonomy it has been working to build.

The revival of nonalignment

A defining characteristic of today’s Indo-Pacific is the resurgence of non-alignment, not as a passive stance but as an active strategy. Countries such as Singapore and Vietnam are actively diversifying partnerships to avoid overdependence on any single power. ASEAN, for its part, continues to leverage its centrality to navigate the competing influences of major powers.

Adefining characteristic of today’s Indo-Pacific is the resurgence of non-alignment, not as a passive stance but as an active strategy.

The signs of this shift are everywhere. Indonesia’s recent entry into the BRICS+ (4) underscores a deliberate effort to hedge between China, the United States, and emerging global players, positioning itself as a balancing force rather than aligning with any one power. Meanwhile, India has maintained an ambiguous (5) stance on Russia, reflecting its broader strategic desire to preserve autonomy rather than be drawn into rigid geopolitical blocs. At the same time, Thailand has deepened (6) its ties with China, but in a pragmatic, transactional manner – seizing economic opportunities without fully committing to Beijing’s strategic orbit. These developments illustrate how regional players are adapting to multipolarity on their own terms, choosing flexibility over fixed alliances.

While the EU often presents itself as a ‘third way’ between the US and China, this framing increasingly feels out of step with regional realities. Indo-Pacific states are not looking for ideological alignment – they want practical, results-driven engagement based on immediate concerns, from maritime security to economic resilience.

Europe’s strategic challenges

Europe’s waning influence in the Indo-Pacific is not just the result of external pressures – it is also a reflection of its own limitations. Chief among these is the lack of coherent and sustained engagement with the Indo-Pacific.

The EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy (7), while an important step in the right direction, has been undermined by the fact that at least five of its Member States have their own distinct Indo-Pacific strategies. Although consistent with the EU’s broader approach, these national strategies hint at diverse priorities that create confusion for external partners. Germany’s economic ties (8) to China, for example, overshadow broader EU efforts, while France’s defence partnerships (9) with India operate largely outside the EU framework.

These bilateral approaches, while valuable, often dilute Europe’s collective influence, making it easier for external actors to exploit internal divisions. This is something China has skilfully done within the ASEAN context (and is increasingly doing in Europe), for example. Indonesia’s recent and confusing announcement (10) that it might cede exclusive economic zone (EEZ) territory to China has opened old wounds within the bloc. For Europe, this serves as a cautionary tale. ASEAN’s struggles with fragmentation and limited enforcement are a reminder that institutional cohesion is an essential safeguard.

The EU’s bureaucratic complexity also hinders its ability to respond effectively. The EU excels at analysing, designing and launching new initiatives, but its commitment often falters over time. In 2020 it unveiled the largely successful ‘Enhancing security cooperation in and with Asia’ (11) (ESIWA) project to the tune of over €15 million to advance engagement in and with Asian countries. Yet since the project’s conclusion in late 2024, it remains unclear (12) what the fate of all the ‘dynamic strategic partnerships’ established will be going forward. Anecdotal reports suggest that requests from partner countries in the Indo-Pacific – such as continued coastguard or cybersecurity training – may be put on hold until further notice. Such incidents not only reinforce (perhaps unfairly) perceptions of Europe as an unreliable actor, but they also frustrate the EU’s partners in the region and create opportunities for other powers to step in.

Economic competition is another front where Europe is struggling to keep pace. The EU’s 2023 Economic Security Strategy (13) emphasises ‘de-risking’ dependencies, particularly on China. Yet Europe remains heavily reliant on Chinese imports, especially in semiconductors and rare earths. Chinese state-owned enterprises are rapidly expanding their production of legacy semiconductors (14), and while these chips may be of lower quality (15), their sheer volume could eventually outpace Taiwan’s output, creating long-term vulnerabilities in Europe’s supply chains.

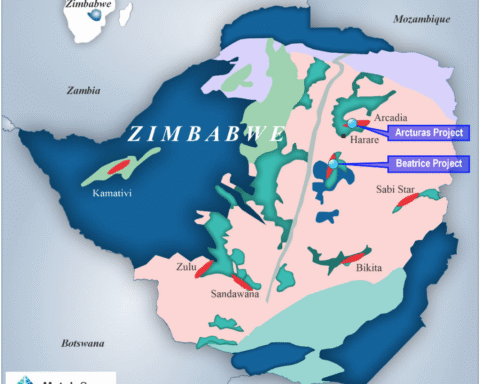

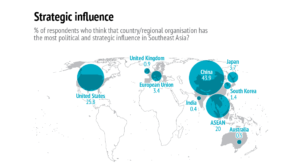

(Data: ISEAS, The State of Southeast Asia: 2024 Survey Report, 2024 )

This internal dissonance is also unfolding at a time when China is intensifying its grey-zone tactics in the South China Sea, exposing the vulnerabilities of regional governance. A worrying example involves reports (16) suggesting that Chinese actors are acquiring strategically placed land in the Philippines, intimidating local communities by making these areas unusable for them, while symbolically reinforcing Chinese territorial claims. For Europe, this highlights the vulnerabilities that come with institutional weaknesses – a lesson it must heed so it can continue to support the region’s governance structures also at the local level.

Security concerns further highlight Europe’s interconnectedness with the region. The deployment of North Korean troops in Ukraine (17) serves as a stark reminder that the Indo-Pacific and European security theatres are not separate. However, a lack of strong regional leadership compounds these risks. Japan (18) and South Korea (19) remain politically fractured, while ASEAN struggles (20) to coordinate a unified response to Chinese encroachments in the South China Sea. If Europe continues to be perceived as detached from these security challenges, it risks being sidelined at a moment when the global order is in flux.

Incremental steps towards reclaiming relevance

Europe’s struggles to reconcile its aspirations for global influence with the practicalities of regional engagement do not have to mean a complete overhaul of its strategy. It must, instead, fine-tune its engagement.

First, consistency matters. Presence counts as much as policy in the Indo-Pacific. Europe’s uneven participation in key regional forums reinforces perceptions of disinterest. Missed opportunities – like the EU’s minimalist presence at Indonesia’s presidential inauguration (21) – send mixed signals in a region where ‘showing face’ carries cultural weight. Public diplomacy needs to be prioritised, with the EU engaging in a manner that is both genuine and resolute to articulate its value as a strategic partner.

Second, long-term commitment is key. It is, unfortunately, not enough to launch new initiatives and expect them to become self sustaining after a set timeframe. The EU must engage for the long haul. Embedding sustainability into project design from the outset is crucial, but so is a more tempered ‘less-is-more’ approach. For example, instead of overly prioritising high-profile – but potentially high-risk – initiatives, the EU could direct more efforts towards sustainable capacity-building projects that target local ownership and foster accountability.

Third, Europe should better harness the ‘Team Europe’ approach – pooling resources, expertise, and relationships to amplify Europe’s collective influence. For instance, leveraging France’s defence partnerships in the Indo-Pacific or Germany’s economic ties with key partners in the region could complement broader objectives. This approach not only helps reduce redundancies and ease strain on limited resources but also provides the opportunity to engage with a wider range of stakeholders.

Fourth, informal cooperation can yield tangible results. Formal inclusion in frameworks like the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM-Plus) should remain a long-term objective, but there are immediate, lower-profile ways to strengthen ties. Since the elevation of the EU-ASEAN relationship to a strategic partnership (22) in 2020, more of these opportunities have opened up. Quiet but impactful initiatives, such as sharing Europe’s experience in developing defence resilience (23) and supporting societal preparedness (24) across a diverse bloc of countries, could build trust and deliver results without the pressure of high-profile scrutiny.

Finally, streamlining bureaucratic processes is crucial. Many Indo-Pacific partners struggle to navigate the EU’s complex institutional frameworks, particularly when accessing procurement opportunities. Establishing clear points of contact and simplifying procedures would make EU initiatives more accessible and effective.

Conclusion

The Indo-Pacific is reshaping the global order, and Europe’s place within it is increasingly precarious. With critical economic and security interests at stake, Europe faces a stark choice: adapt to the region’s evolving realities or risk irrelevance. The Indo-Pacific is not merely a distant theatre of competition; it is a pivotal axis for global trade, technological innovation, and security dynamics. Europe must demonstrate that it is more than a passive observer by committing to concrete and sustained partnership. This critical moment of geopolitical flux is an opportunity for Europe and the Indo-Pacific to fine-tune their relationship. The costs of inaction are far too high—not just for Europe, but for the global balance of power.

References

(1) Jacqué, P., ‘War in Gaza: The European Union’s diplomatic failure’, Le Monde, 5 June 2024.

(2) Press Trust of India, ‘Europe has to grow out of mindset that its problems are world’s problems, says S Jaishankar’, The Economic Times, 4 June 2022.

(3) Borrell, J., ‘The EU approach to the Indo-Pacific: Speech by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)’, European External Action Service, 3 June 2021.

(4) Jailani, A.K., ‘Indonesia’s entry into BRICS: Reshaping the global legal order’ The Jakarta Post, 9 January 2025.

(5) Kugiel, P., ‘India’s ambivalent stance on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine’, The Polish Institute of International Affairs, 3 March 2022.

(6) Sato, J. and Yaacob, R., ‘Is China replacing the US as Thailand’s main security partner?’, The Lowy Institute, 2 December 2023.

(7) EEAS Press Team, ‘EU-Indo Pacific Strategy’, 30 January 2024.

(8) Kratz, A. et al., ‘Don’t stop believin’: The inexorable rise of German FDI in China’, Rhodium Group, 31 October 2024.

(9) French Embassy in New Delhi, ‘India – France Joint Statement on the State Visit of H.E. Mr. Emmanuel Macron, President of French Republic, to India (25 – 26 January 2024)’, 26 January 2024.

(10) Darmawan, A.R., ‘Has Indonesia fallen into China’s nine-dash line trap?’, The Lowy Institute, 12 November 2024.

(11) European Commission, ‘Enhancing Security Cooperation in and with Asia’.

(12) ESIWA, ‘Terms of Reference’.

(13) European Commission, ‘An EU approach to enhance economic security’, 20 June 2023.

(14) Shilov, A., ‘Analysts warn China’s aggressive chip fab expansion could lead to future price war’, tom’s Hardware, 16 January 2024.

(15) Rühlig, T., ‘Curbing China’s legacy chip clout: Reevaluating EU strategy’, Brief no. 21, European Union Institute for Security Studies, 13 December 2024.

(16) Victoria, V., ‘Four Chinese nationals arrested for acquiring assets in the Philippines using illegally obtained government-issued IDs and birth certificates’, Taguig.Com, 2 April 2024.

(17) Ng, K., ‘What we know about North Korean troops fighting Russia’s war’, BBC News, 24 December 2024.

(18) Lewis, L., ‘Japan votes in closest election in years as LDP faces “major headwind’’’, Financial Times, 27 October 2024.

(19) Davies, C. et al., ‘The historical traumas driving South Korea’s political turmoil’, Financial Times, 9 December 2024.

(20) Chap, C., ‘ASEAN remains divided over China’s assertiveness in South China Sea’, Voice of America, 12 September 2023.

(21) Paat, Y., ‘Regional leaders attend Prabowo’s presidential inauguration’, Jakarta Globe, 20 October 20224.

(22) European External Action Service, ‘EU-ASEAN Strategic Partnership’, 1 December 2020.

(23) Andersson, JJ., ‘Delivering together: Targeted partnerships for a secure world’, Brief no. 7, EUISS, 23 May 2024.

(24) Niinistö, S., ‘Strengthening Europe’s civil and military preparedness and readiness: Report by Special Adviser Niinistö’, European Commission, 30 October 2024.