For days, the statements made by MHP (Nationalist Movement Party) leader Devlet Bahçeli have been the topic of the agenda, with various evaluations made regarding the timing of these remarks. Different implications are tried to be derived from different interpretations and justifications that have been produced by commentators, and even conspiracy theories have been proposed. Of course, discussing with and talking to each other about the statements is valuable. However, it is upsetting to see that most of the debaters and speakers are unaware of Türkiye’s activities on this issue.

Türkiye’s Quest for Solution

If the minutes of the National Security Council (MGK) meetings held in the last 46 years were disclosed, it would be clearly seen that the terrorist activities carried out by the PKK, the measures to be taken aganist it and the democratization efforts were the main agenda items of all meetings. On the one hand, a continuous struggle against the terrorist organization is maintained, and on the other, the question of “is there another remedy?” remains on the agenda. So the search for a solution is never postponed. These activities include attempts by the September 12 coup leaders to understand the situation, efforts by leaders like Turgut Özal, Süleyman Demirel, Tansu Çiller, and Mesut Yılmaz to understand the situation and to explore possibilities of solution through intermediaries, Necmettin Erbakan’s initiatives to establish contact via Syria and search for a solution, the 57th government led by Bülent Ecevit engaging in discussions through MIT (National Intelligence Organization) officials with Öcalan, and similar attempts by the February 28 regime and AK Party governments that has attempted to analyzing that the solution possible or not through MIT officials and policies implemented to achieve the solution.

It is noteworthy that leaders with significantly different political views have consistently kept the question of “is there a solution without guns?” on the agenda. However, further steps have been hindered due to the political costs of such actions and the insistence of the security bureaucracy to retain its dominance over the issue. In this context, it is fair to state that President Erdoğan, during his tenure as Prime Minister, was the only leader to demonstrate a clear willpower to achieve a resolution. Unfortunately, these efforts that show the quest for solution were undermined by different excuses and their positive results were prevented.

Bahçeli’s Statements and Historical Documents

The most comprehensive statement on the discussions about solving the issue, that has pionered with greetings in TBMM by Bahçeli and maintained at the MHP’s three group meetings, was made by Bahçeli during the group meeting on October 22. In his speech that four pages allocated to the issue, Bahçeli explicitly called for the PKK to “lay down arms.” Many interpreted his statements literally, leading to debates over whether Öcalan would be released from prison and allowed to address Parliament. However, Bahçeli’s initiative, expressed from his own perspective, should be seen as a declaration of determination and willpower to change the status quo. Actually, Bahçeli aimed to convey to those who approached the initiative he put forward with instrumentality and/or scepticism how vital he considered the issue and how determined he was to find a solution Therefore it is not correct to interpret the proposal only in its literal sense.

Following Bahçeli’s statements, what needs to be recalled is the solution process. During this process, only two fundamental statements were made: first was the 2013 Newroz Declaration, which called for the organization to lay down arms and withdraw, and the the second was 2015 Dolmabahçe Declaration, which proposed that the organization convene to renounce its theses concerning Türkiye. The issues raised by Bahçeli align with these two documents, in which Öcalan instructed the organization to “do what is necessary.” This is already well-known, and thus the surprise at Bahçeli’s statements can only be attributed to the fact that they were made by him.

Türkiye’s Experiences

Global examples show that the adopted approaches by the governments to disarmament of any terrorist organization depend on the reasons for the emergence of organization, the tools they use, the social structure they emerge in, and the damage caused. What is appropriate for one case may not be suitable for another. Therefore, issues such as ending terrorism should not be discussed solely within the framework of “conflict resolution theories” but rather within their unique contexts. Given Türkiye’s past efforts and experiences, it is clear that a broad range of activities has been implemented to resolve the issue. Negotiations abroad and the involvement of international observers were tested in the Oslo talks, but this attempt was sabotaged. Various methods were tried during the expansion and resolution processes, and efforts were made to discuss the issue on a societal level. The lesson to be drawn is clear: learning from past experiences is essential.

After Bahçeli’s statements, it is worth highlighting two unhealthy attitudes. The first is the insistence by some so-called “experts” on adopting certain practices derived from specific contexts, which may have been meaningful under the conditions of the countries where they were implemented. It is clear that advocating templates without analyzing the particular conditions of the relevant country does not contribute to the solution. Assessments such as, “These steps were taken in that country’s resolution process, and because we didn’t implement them, we failed,” are misguided and irrelevant. The second issue pertains to the attitude exhibited by some bureaucrats, which can be summarized as, “Counterterrorism is our job.” What is clear is that any situation involving the safety of citizens is not merely a “job,” nor is it an area for testing academic claims. These are urgent matters requiring immediate solutions from those who govern the country.

The Issue of Addressee

Bahçeli’s statements also touch upon the issue of interlocutor, which remains a taboo subject despite being exceeded during the resolution process and is frequently raised by the PKK and its affiliated institutions. It is well known that the PKK has an extensive network of sub-organizations. When topics such as disarmament or ending terrorist activities come up, a broad spectrum of the organization, including its core structure, political branches, and civil society organizations, often states, “Öcalan is the interlocutor.” Some even go further, declaring, “Öcalan is our willpower.” These two statements essentially mean, “Don’t talk to us, talk to Öcalan; whatever he says, we will accept.” In the face of this situation, the natural outcome is to engage with Öcalan and directly ask whether he can take a clear stance for the organization to disarm. However, it is also useful to recall the resolution process. The two foundational texts of this process—the 2013 and 2015 declarations—are still on record. While Öcalan who referred to as the “our willpower,” gave instruction for diarmament, PKK itself had lingered and did not follow the order. Yet the directives in these texts did not include any additional conditions or stipulations. The basic issue is whether what the person called addressee/willpower says will be done or not, rather than who the addressee is. The 2013 and 2015 declarations and the behaviors exhibited during that period remain fresh in memory and have not been forgotten.

The Situation of the PKK

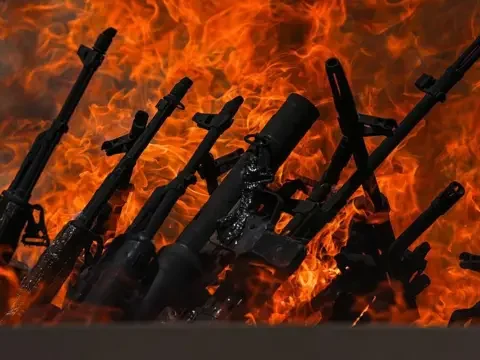

First, it must be stated that it is difficult for an organization with international connections to lay down arms and disband itself on its own willpower. This is particularly true for an organization like the PKK, which was founded on the basement of Russian perception of the 1970s and 1980s that shaped by Stalinist Soviet influence, then moved forward in the 1980s and 1990s with motivation from Iran and Europe, and gained geopolitical status in the 2000s with support from the U.S. and Russia. Additionally, the PKK has a heavy baggage of internal conflicts fueled by motives of revenge. It becomes even harder for such an organization to take the kind of steps we are discussing. The rational approach, then, is to engage directly with the individual identified as the organization’s “willpower” and presented as its “interlocutor.” This engagement must be conducted on a rational basis, discussing the reasons why it regarded gun as a tool for its goals, evaluating the outcomes of this choice, and analyzing the relationship between the organization’s established status qou and the reasons for its use of guns. This is a sound and logical assessment. At the same time, it is critical to emphasize that an organization that has declared it has no territorial claims in Türkiye no longer has any justification for maintaining its armed existence.

The possibility exists, however, that the PKK’s armed central staff will avoid such a assessment. For them, this issue represents their “job.” The responsibility then falls on civilian actors. Those who involved in political and NGO’s struggles should reflect on this assessment. Such efforts could not only be meaningful but also influence the organization’s armed central staff. We all know that comparing pain by telling stories about mistakes made does not produce any positive results. The question is this: Can the establishment of a democratic state or the democratic transformation of the state become a common demand? If the answer to this question is genuinely “yes,” then a stance should be taken to support this demand and allow its realization. Watching an organization or another entity obstruct this possibility is not the right course of action. Hundreds of valid reasons could be listed regarding past actions, but historical grievances such as oppression, denial, or assimilation should not serve as excuses to waste this historical opportunity. Instead of being captive to the pain and mistakes of the past, the focus should be on building the future with a more constructive vision and an inclusive imagination.

Talking to the “Addressee”

One of the problems in Türkiye is the nature of the relationship between the PKK and political structures. This issue is rarely discussed. If references to global examples must be made, this should be the primary focus. However, due to ideological positions, this issue was not discussed. Those who talk about similar experiences around the world also choose to ignore this relationship issue. The unspoken issue is the form of the relationship between the PKK and the political party. In many global examples, political parties and leaders direct the organization, and the organization complies. While there are minor nuances, the political structure has been the determinant. But the PKK case, is an exception. It is often discussed that the political wing “receives instructions” from the armed organization in various ways. This poses a significant issue for Türkiye. Another dimension of Bahçeli’s approach is that it provides a basis for questioning this flawed relationship. That’s why the initiative suggested by Bahçeli for the organization to lay down its arms through Öcalan is also important in this respect.

Therefore, to avoid attitudes that prolong the process and to prevent disruptive interventions, the essential step is to engage with Öcalan and clarify whether he can take a direct stance for the PKK to disarm or not. If this issue is resolved at this point, the remaining parts of the issue can be managed more smoothly. Türkiye has clearly seen that expanding the number of interlocutors, prolonging discussions, and changing the subject do not yield beneficial results. Moreover, considering the statements made, one of the main reasons why this effort is meaningful is that the activities regarding the democratic transformation of the state are separated from the activities carried out by the PKK. This in itself is a positive development. Therefore, within the clarified scope and framework, a meeting should be held with Öcalan and it should be discussed clearly whether he can take the initiative on the issue and convince the organization to lay down the arms without further delays. If a clear, definitive, and positive willpower emerges, the process can be followed, and the necessary actions can be planned and implemented.

What Is the Great Türkiye Quest?

The goal or ideal of a Great Türkiye can be defined in two different ways depending on the two different political stances. The first stance is based on a notion of “greatness” rooted in the use of power, an empty rhetoric of historical heroism, and an approach that views everyone as an enemy. However, such approaches produce temporary, short-term results at best. Therefore, the emphasis on “greatness” in this context is not genuine. The second, and correct approach involves implementing a perspective that emphasizes a strong democratic transformation, a justice system that treats all citizens equally, and a governance model that is transparent and accountable. True greatness can be achieved through this stance. I am aware that these concepts are frequently used and often their contents diluted by many. Nonetheless, we have no choice but to stand behind what we believe is right and to fight for it. Whether the PKK lays down arms or not, implementing this understanding should be the first step in the quest for a Great Türkiye.

Achieving a Great Türkiye requires increasing capacity, diversifying resources, expanding vision, and strengthening resolve. This involves ensuring domestic peace, minimizing societal tensions, and reinforcing the sense of citizenship and belonging. If we all contribute to realize this, the impossible can become possible. What we must do is not repeat past mistakes but channeling this sentiment into democratization and a better governance agenda. Constructive politics and a positive agenda demand this. The precondition for the quest for a Great Türkiye is the demand for a profound paradigm shift and working for demanded transformation. This means adopting a political perspective and strong willpower that prioritize solving all chronic issues involving the state and its citizens within the framework of the state’s democratic transformation. It means bringing the principle “God commands goodness and justice” to bear on every aspect of life, defending the good we know solely in the language of goodness, and ensuring that ethnic differences cease to be causes of division and conflict. It means replacing the perception of “a citizen with duties” with “a person with inviolable rights.” To achive Great Türkiye purpose, these musts can be multiplied further and they are both possible and achievable.

Briefly a perspective that strengthens internal cohesion, maintains an inclusive and flexible sense of identity, and approaches the concept of “us” from a pluralistic rather than a monistic standpoint and an approach that regards its borders not as barriers than bridges, lays a strong foundation for the journey toward a Great Türkiye. Türkiye is a post-imperial state—a nation that is the remnant of an empire. For example, Istanbul, the city with the largest Kurdish population in the world today, has served as the capital of two global empires with very different worldviews. For this reason, Türkiye must approach all its issues, including the Kurdish issue, with this self-confidence. It cannot address its problems with the feelings of insecurity that late-forming nation-states have or as a entity found a place on the stage of history by the twist of fate.

Tiny fears, archaic clichés, monist and assimilationist slogans will lead us nowhere. Only with self-confidence, a broad vision for the future, and an inclusive approach to identities we can emerge stronger from the storms of the global system and regional turbulances and move closer to the achiving goal of a Great Türkiye.