For all that has been written and said about migration in recent years, a security-based perspective continues to dominate coverage of the topic. The result is a vicious cycle in which the prevailing rhetoric leads people to perceive migrants as a threat, which leads politicians to double down on fear-based rhetoric and policies.

Of course, security is an important consideration for anyone trying to manage a phenomenon as multifaceted as migration. But focusing disproportionately on security is not only inaccurate; it also forecloses the kind of comprehensive approach that the issue requires. Crafting a successful migration policy is a long-term enterprise. It should not be driven by short-term electoral cycles or populist pressures.

Among the many neglected facets of migration is its close link to economic progress, which we document in a recent policy report for the Global Forum on Migration and Development in Colombia. Without understanding and focusing on this link, migration governance risks becoming self-destructive for source and destination countries alike. Our research shows that bad migration policies damage the economy, weaken social integration models, erode democratic norms and freedoms, and threaten to create permanent demographic imbalances.

Many countries already appear to be in the early stages of population decline, rising old-age dependency, and mounting fiscal pressures. As these trends continue, pension systems will come under strain, labor shortages will become more frequent, economic growth may slow, and existing inequalities will deepen. While migration cannot single-handedly solve these problems, it is a fundamental component of any serious program to promote productivity, healthy aging, and full labor-force participation. These socioeconomic benefits rarely feature in political debates about immigration, even when related issues such as inflation and public debt are front and center.

To be sure, the levels of immigration needed to ameliorate demographic decline in many countries are politically unrealistic, and unmanaged immigration flows do raise legitimate concerns – particularly when integration systems are weak. But the current, increasingly prohibitionist response is destined to fail. Migration is a central feature of the twenty-first-century economy, and it will play an increasingly prominent role in shaping or hampering future development. This means it represents a huge opportunity for countries that manage it well.

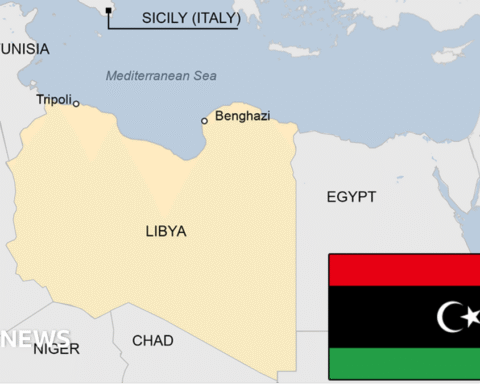

Managing migration well starts with considering the perspectives of all involved. We need more global and regional partnerships between origin, transit, and destination countries. Given their power and wealth, destination countries are essential for any meaningful collaboration. But their citizens too often forget that most of the world’s migrants and refugees are hosted by poorer countries; and that migrants begin and pass through other countries before arriving at the Global North’s doorstep. The irony is that while migration could benefit wealthy northern countries, its effects on transit countries are neither neutral nor necessarily harmless.

One major complication is that the infrastructure of migration makes it difficult for would-be migrants to access regular pathways. Many countries provide outdated and opaque information about immigration opportunities, and visa processes do not encourage regular, safe migration. As a result, there is a greater incentive for smuggling and exploitation. In this context, public platforms that clarify eligibility criteria and explain procedures in different languages could be very useful. At the same time, complementary legal pathways – education, labor, family reunification, or humanitarian channels – need to be expanded and adapted to meet the needs of today’s mixed migration flows.

Looking ahead, advocates of a more sensible approach should focus on three essential objectives. First, migration policy must be insulated from short-term politics. Decisions should be based on data, not fear. Migratory policy is a long-term public policy investment that will suffer if migrants are scapegoated and vilified for political purposes. As with monetary policy, the more that migration policymaking can be moved from partisan political arenas to independent, evidence-bound institutions, the better.

Second, migration policy must be more firmly embedded in a broader multilateral framework. Origin and destination countries alike can benefit from collaboration to prevent brain drain, facilitate orderly passage, and ensure that remittances contribute to long-term development. No country can manage these complexities alone. We need to frame migration not as an emergency but as a permanent feature of our interconnected world. Coordinated international agreements can help align the interests of sending and receiving countries, balance economic imperatives with social cohesion, and avoid the zero-sum mindset that too often clouds migration policy. Ultimately, there is no other way to prevent both the depletion of human capital from emerging economies and the political backlash that destabilizes mature democracies.

Third, we must invest in integration and public messaging. Migrants are too often perceived as a burden, when in fact they are drivers of economic growth and cultural vitality. Inclusive policies – providing access to jobs, education, and local civic life – are essential not only for migrants’ success, but also for democratic resilience. Where migrants are seen and treated as valuable members of society, support for humane policies grows. Where they are excluded or criminalized, polarization follows. The real payoff comes when migrants are given the tools to contribute – through employment, entrepreneurship, and civic participation – and when host societies make room for new forms of belonging.

In many democracies nowadays, migration is discussed in visceral, emotional terms that bear little resemblance to reality. Border enforcement alone cannot prevent irregular migration; it can only displace or delay it. If people believe they can build safer, more prosperous lives elsewhere, they will try – legally or not.

Migration is one of the most complex policy challenges of our time; but it also represents a major opportunity for aging societies. We can allow the issue to be hijacked by fearmongers, or we can approach it with coordination, courage, and clarity by implementing policies rooted in evidence, governed by cooperation, and animated by a spirit of inclusion and fairness. The solution is not to criminalize hope, but to manage it with dignity and strategic foresight, so that it becomes a force for shared global development and prosperity.

*Carlos Alvarado-Quesada, a former president of Costa Rica (2018-22), is a member of the Club de Madrid.

*Katrina Burgess is Professor of Political Economy and Director of the Leir Institute for Migration and Human Security at Tufts University’s Fletcher School.