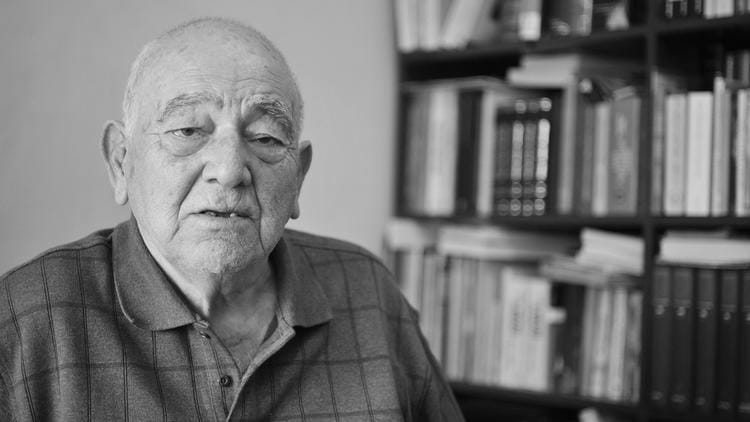

While Kemal Karpat made the loss of Muslim lands belonging to the Ottoman Empire or neighboring Muslim lands leading to emigration, which in turn led to national-political developments his field of study and research, he emphasized two concepts in particular: Identity and ideology. Identity refers to Turkishness, the Turkish Nation, and ideology toIslamism. In his 900-page book Islam’ın Siyasallaşması (The Politicization of Islam), which can be considered as the fruit of his lifetime, and in his other works, Kemal Karpat states not only between the lines but also in the lines that Muslims became a nation through Islam andIslamism, and that they called the name of the nation the Turkish Nation.

“Over time, individual Muslim citizens began to identify themselves with this new structure, composed of different tribes and ethnic groups, but with Islam as the unifying ideology andTurkish as the official language. This was the territorial state, the homeland, the homeland to which all Muslims pledged allegiance and loyalty in its ideal form… Those who study Turkish culture and society inevitably conclude that the Turkish nation was in some way an extension of the Muslim nation that emerged in the nineteenth century from the Islamic nation…[This] Turk was neither a European nor a Central Asian Turk. It was a new Turk with an old name. That is, it was the nationalized Muslim of the Ottoman Empire. The intellectuals who identified with the state, regardless of their ethnic origins, saw themselves as Turks as a super-identity. Thus, the unity of religion among some of the intellectuals became the basis of the national, that is, Turkish identity and became politicized. [This society, whose language is Turkish and religion is Islam, is a proto-national Turkish society”.

In this context, the late Karpat directed harsh but implicit and scholarly criticisms at theKemalist conception and construction of Turkishness, often without naming names, and while explaining the transformation of the Ottoman nation system, he stated that “nationality, despite claims to the contrary, became defined first by religious affiliation and then by language”. According to the deceased, “a Turk in Ottoman times could be anyone who belonged to a Muslim nation”. As is well known, the Balkan Christians, while having the same religion and sect, separated and became independent by emphasizing their ethnic origin, but the Muslim elements were united in Turkey and became “Turks” thanks to their religious affiliation, not their ethnic origin. Albanians, Pomaks and Bosniaks who migrated to Turkey were Muslims, so they easily fused in the new homeland and became Turks. I think it was Karpat who first found the scientific explanation of “becoming a Turk by relying on Islam”. Karpat “thought that it was both unnecessary and misleading to look for the origins of Turksin Central Asia in ‘race’”, not only because he was educated in a madrasa, his father was an imam, he himself was an imam for a short period of time and he was pious, but also because it went against the leaven of the land where he was born and raised. On the other hand, he specifically emphasized his ethnic Turkishness.

One of the most important aspects of Kemal Karpat’s books is that he includes the ethnic origin of the names he mentions. Hodja consciously emphasized ethnic origin in his definition of the Turkish Nation. Because he described the Turkish Nation as a new nation based on Islam, formed by Muslims of different ethnic origins through migration and marriage.

Kemal Karpat is someone who has explained history in a way that can be called perfect. First of all, he was able to combine history with fields and elements such as culture, economics, religion, sociology and political science. His religious background has also made a significant contribution to his being “the river that pierces the mountain”.

One of the phenomena that makes Kemal Karpat, Karpat is the tragic migration he experienced. So much so that migration could have an incredible impact on the formation of a nation: “The immigrants called themselves Muslims rather than Turks, whereas most of thee migrants from Bulgaria, Macedonia and Eastern Serbia were descendants of the Turks who settled in the Balkans in the 15th and 16th centuries”. “By the end of the 19th century, immigrants and their descendants made up thirty to forty percent of the total Anatolian population. In some Western regions this proportion was even higher. Large numbers of immigrants were assimilated into the Anatolian environment with relative ease. This is because the Qur’an commands that the muhajirs be given all possible help and treated as brothers and sisters, and these provisions were supported by the instructions of the caliph himself and the settlement measures taken by the government”. These lines, in which belief and determination are intertwined, were the basis of his scholarly-academic work.

As can be understood from the above explanations and quotations, Mr. Kemal Karpat was a scholar with convincing determinations in the definition of Turkish identity and the Turkish Nation.

“The intelligentsia, as mentioned earlier, was identified with the state and ‘Turkishness‘, but this was due to its language, and this Turkishness did not carry much political meaning and was not seen as a completely separate concept, but as part of multiple identities. Already in the 1880s, ‘Ottoman‘, ‘Turk‘ and ‘Muslim‘ were seen as synonymous. There was nothing incompatible with being a Tatar, Bosnian or Kurd in the new sense of being a Turk… This voluntary adoption of Turkishness by non-Turks may have been facilitated by the influence of common religion and history, or it may have been the result of an intuitive knowledge that they were building a new society together (as a result of migration)”.

Karpat tirelessly explained that neither history nor the phenomenon of the Turkish Nation can be understood without a thorough understanding of the phenomenon and issue of migration, “With the loss of the lands held by the Ottoman Empire, Muslims in the lost lands migrated to the remaining lands; With the marriage institution of Islamic Law, they fused with the local people and put ethnic differences in the second plan and even forgot them, and thus, the local people and the muhajirs, regardless of their ethnic origin, formed a new nation centered on religion, centered on Islam”.

He insisted that the most important cause of some of the most troubling events in our history was the migration from the lost lands to the retained lands. In this regard, he pointed out and touched upon the Armenian deportation. Unfortunately, this phenomenon has been neglected in its time, and no second name other than Kemal Karpat has come to the forefront, especially on the international platform, to keep this issue alive and alive. The fact that the phenomenon of migration has recently begun to be taken seriously seems to indicate that we have begun to understand the background of the complicated issues. Migrations to existing lands are not a thing of the past; they are an essential element of today’s identity issue. Kemal Karpat has tried to place this issue in a scientific framework that is far from being sentimental.

In addition to his versatility and mastery of the migration phenomenon arising from immigration, he also seems to have gained a depth from his legal background. Burhan Apaydın, Fuat Hulusi Demirelli, Haluk Eczacıbaşı, İsmail Hakkı Talas, İsmet Tümtürk, Naci Şensoy, Necdet Çobanlı, Nurullah Kunter, Oktay Uzunçarşılıoğlu, Orhan Adlî Apaydın, İsmail Arar, Reşit Ülker, Selçuk Özçelik, The late Kemal Karpat, who was among the 1295 lawyers registered to the Istanbul Bar Association in the 1951-52 roster, which included names as different as Süha Özgermi and Hıfzı Topuz, graduated from the Istanbul LawFaculty and seems to have realized the benefits of being a lawyer not professionally but scholarly-academically. The influence of Public and Constitutional Law on his social-political historiography is undeniable. The effort to prevent the separatist movements of different religious-ethnic elements and to keep these elements under the same roof was not only a military, but also a political and legal issue. He was able to perfectly fuse his deep interest and knowledge in different fields.

At times, Kemal Karpat offered gentle but strong criticisms to common beliefs. For example, he argued that the ayān were an indigenous and conservative class that continues to be influential today: “The ayān were not ‘overlords‘ or ‘usurpers of public property‘ as the officialOttoman-Turkish history defined them. In fact, they were the vanguard of a new middle class that had begun to fight the bureaucracy for control of the land, the economic basis of state power, and had put their signature to many of the ideologies of the reform movement in theOttoman Empire, including Islamism and nationalism. The Sultan and his bureaucrats were the actors who implemented the reforms, but the real driving force was the middle classes who changed the Ottoman political system from within, whether it was their own work or the work of some bureaucrats sympathetic to the reforms. Unlike the upper mercantile group of Greeks and Armenians, who mostly served European economic interests, the agrarian middle class was mainly Muslim (although Christians in the Balkans managed to achieve some degree of equality). While the rise of the agrarian middle class influenced the emerging new social order, its modernist traditionalism influenced the structure and philosophy of the surviving old scholars (ulema) and the new intelligentsia, causing them to split into various factions opposing each other on issues of change, modernization, Islam and nationalism. The generally culturally conservative and traditionalist agrarian middle class strongly support edits own brand of modernism and Islamism; to dismiss the agrarian elements of this new classas ‘conservative‘, ‘traditionalist‘ or ‘reactionary‘ would be to ignore its vital role in shaping the socio-political order of the modern Ottoman and contemporary Middle East”.

Kemal Karpat has pointed out the danger of confining history to archival documents, document literacy and chronology by relying on documents but equally valuing the socio-cultural values, intellectual development, conjuncture and the course of events of the day, and as a result, he has become a political-social historian who looks at issues from a wide perspective with the help of different fields.

Although Kemal Karpat has frequently mentioned the atrocities and migration of Muslims, he has not fallen into repetition, has not become tiresome – in fact, the subject has not been exhausted, on the contrary, new evidence, perspectives, determinations and interpretations have been brought forward day by day – and he has not been subjected to any serious political or scientific criticism because his evidence is strong and his approach to the subject is striking.

The late Karpat, who constantly emphasized that the foundation of Turkish identity is Islam, was probably also giving us a subtle advice and warning: “Never forget this fact and be united”.

May Allah Almighty have mercy on him!

Note:

1-Karpat has been vilified by Armenians as well as some dummies for having spoken out loudly in the international academic community about the massacres and migrations of Ottoman Muslims.

2- Hoca, perhaps out of necessity, praised the May 27 coup d’état. However, he always gave the impression that he was ashamed of this.

3- Karpat, by mentioning the population in the Ottoman lands together with the migration, has very skillfully tried to reveal the meaning of the number and proportion of Muslims in the lands from which they were expelled.