July 24 marked the anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne. As every year, articles were written and speeches were made about it. It was widely proclaimed that Treaty of Lausanne is the deed of the Republic, that it is unchangeable, and that it will last forever. Those who criticized the Treaty of Lausanne, which had been turned into a sacred text, and who said that the treaty was an imposition of the conjuncture and that it could be revised with changing global conditions, were accused of ignorance and nonsense.

Of course, historians who claim that Treaty of Lausanne will last forever are not unaware that no treaty in history has had such permanence. Somehow, when it comes to Treaty of Lausanne, it is not scientific reasoning but blind dogmatism that prevails and in an effort to perpetuate this imposition, the elites who sanctify the treaty side with those who forced our state to sign it during difficult times. Moreover, they do so under the guise of nationalism or patriotism.

The borders defined in various documents presented during the post-World War I peace negotiations reflect both the rage of the invading enemies who wanted to destroy the Ottoman Empire and the determination and efforts of those who tried to preserve the homeland.

As we will discuss below, these documents include the Ottoman Memorandum dated June 23, 1919, submitted to the Paris Conference, the National Pact (Misak-ı Millî) Declaration, the Treaty of Sèvres, and the Treaty of Lausanne. The Sèvres and Lausanne treaties were peace agreements imposed by the Allied Powers to divide our state, while the Ottoman Memorandum and the National Pact Declaration defined the homeland borders declared by the state in resistance to the enemy.

The measure of success achieved should be measured by the success in protecting these declared borders, not by the relative harm caused by documents prepared and imposed to be signed by the enemy.

In this article, I will write about the efforts to partition the homeland during the period from the Paris Conference to the Treaty of Lausanne, and the struggles to resist this partition plans.

The Paris Conference Process

As is known, World War I ended with the defeat of the Central Powers, which included the Ottoman Empire, and the war formally ended with armistices signed in 1918 between the defeated states and the victorious Allied Powers. For the Ottoman Empire, this was the Armistice of Mudros signed on October 30, 1918.

It is a principle that every armistice is to be followed by a peace treaty. Accordingly, the Paris Conference, which began on January 18, 1919, became the venue for peace negotiations between the victors and the defeated. A total of 32 countries that had fought or declared war against the Central Powers participated. The negotiations, held within the framework of Wilson’s Fourteen Points, resulted in peace treaties with the Allied Powers; the Treaty of Versailles with Germany on June 28, 1919; the Treaty of Saint-Germain with Austria in September 1919; the Treaty of Neuilly with Bulgaria on November 27, 1919; and the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary on June 4, 1920.

Despite multiple attempts, the Ottoman Empire was not invited to the Paris Peace Conference and was intentionally excluded.

The Ottoman Memorandum of June 23

The Ottoman Empire was invited to the Conference on May 30, 1919, after having the occupation of Izmir by the Greeks on May 15. A diplomatic delegation headed by Damat Ferit Pasha that appointed by the Council of Ministers (now equivalent to the Cabinet) submitted an official memorandum titled “Müdâfa’a-nâme” (Statement of Defence), to the Conference on June 23, 1919. This memorandum reflected the Ottoman government’s official stance on the Turkish peace and was prepared by a government-appointed commission. Most importantly, it was approved by the Council of Ministers. (i) (For the original text of the memorandum, you can refer to pages 200-205 of the journal in which the article in the footnote was published first time.)

The summary of the memorandum submitted to the Conference Chairmanship is as follows:

- Edirne and Western Thrace, where Turks formed the majority, would remain Turkish, based on the borders established in the 1878 Berlin Treaty.

- In Anatolia, Turkish borders in the east would remain as they were before the war; Mosul and Diyarbakır, along with part of Aleppo, would be within Turkish borders.

- Islands close to the coast, historically belonging to the Ottoman Empire, would remain Ottoman territory with broad autonomy.

- If an Armenian Republic was established in Yerevan, a referendum was held regarding the border line, and the Ottoman Empire would grant cultural and economic rights to the Armenians remaining in its territory.

- Arabia, Syria, the Hejaz, Yemen, Iraq, and other parts of the Ottoman Empire would be governed with administrative autonomy under the Sultan, who would maintain a limited number of representatives and guards in Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem.

- The issues of Egypt and Cyprus would be negotiated with Britain to find a resolution. Upon the signing of the treaty, occupying troops would withdraw from Ottoman lands. The Ottoman people favored unity and independence.

The memorandum was based on the pre-war borders and rejected the detachment of occupied homeland territories. It infuriated the Allied Powers. On June 25, 1919, they issued a counter-memorandum asserting that the fate of the Ottoman Empire would be decided by the Allied Powers and insulted the Turks. Though the June 23 memorandum was not accepted at the Paris Conference, it served as a historical declaration of the state’s natural borders.

Misak-ı Millî (The National Pact) Declaration

The Memorandum dated June 23, 1919, served as a source for the National Pact (Misak-ı Millî) Declaration, which was adopted by the Ottoman Parliament on January 28, 1920.

According to the National Pact Declaration (ii), the state’s borders were defined as follows:

Since the fate of the parts of the Ottoman Empire where only the Arab majority lived and which were occupied by enemy armies at the time of the signing of the Armistice of Mudros on October 30, 1918, will be determined by the free votes of their inhabitants, all the parts inhabited by the Ottoman-Islamic majority, both inside and outside the said armistice line, united in religion, race, and ideals, filled with mutual love and self-sacrifice, and fully respecting local conditions with their customary and social rights, are truly and de facto a whole that cannot be separated for any reason.

For the three provinces (Kars, Ardahan, Batum), which had joined the homeland through the people’s vote when they were first freed, it was agreed that a new vote could be held if necessary.

The legal status of Western Thrace, which was to be included in the Turkish peace agreement, should be determined according to the free will of the people living there.

The city of Istanbul, which is the center of the Islamic Caliphate, the Ottoman sultanate and government, and the Sea of Marmara must be protected from all kinds of threats. Provided that this principle remains in effect, the decision taken jointly by us and all other interested states regarding the opening of the Mediterranean and Black Sea Straits to world trade and transportation is valid.

Within the framework of agreements made between the Allied Powers and their enemies or some of their partners, the rights of minorities would be confirmed and guaranteed by us on the condition that Muslims in neighboring countries were granted the same rights.

In order for our national and economic development to fall within the realm of possibility and for us to attain a more modern administration, it is the fundamental basis of our life and survival that we, like every state, have full independence and freedom in obtaining the means of development. Therefore, we oppose any restrictions that would hinder our political, judicial, financial, or other development. The terms of repayment of our debts must not conflict with these principles.

Whereas the Ottoman Memorandum used pre–World War I borders as a reference point, the National Pact referred to the borders held de facto at the time of the armistice on October 30, 1918. On the map drawn based on the National Pact, today’s Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Iraq up to the Alexandria–Port Said line, as well as the Islands, Cyprus, and Batum, were included within the borders of the state.

On March 16, 1920, the Allied Powers officially occupied Istanbul, raided the Ottoman Parliament, arrested leading deputies and intellectuals, and exiled them to Malta. A new National Assembly was established on April 23, 1920, in Ankara by deputies who had made their way there. On June 18, 1920, the Ankara government declared to the world that it would adhere to the principles of the National Pact in foreign policy.

The Treaty of Sèvres

At the San Remo Conference held from April 18 to 26, 1920, representatives of the Allied Powers discussed the partitioning of Ottoman territories and drafted the Treaty of Sèvres to be signed with the Ottoman Empire. On April 22, the Ottoman government was invited to the peace conference in the suburb of Sèvres near Paris. Sultan Mehmed VI (Vahdettin) sent a delegation to Paris headed by former Grand Vizier Ahmet Tevfik Pasha. On the following day, April 30, the Grand National Assembly convened in Ankara and sent a letter to the foreign ministries of the Allied Powers stating that a separate government had been established in Ankara.

Seeing the harsh conditions of the Treaty of Sèvres, Ahmet Tevfik Pasha withdrew from the negotiations. The Istanbul government refused to sign the treaty for a long time. However, in order to pressure the Turkish side, the Allied Powers pushed Greek forces in İzmir deep into Anatolia (toward Balıkesir, Bursa, Uşak), and Thrace was quickly occupied by the Greek army. As the enemy began advancing toward Istanbul, the treaty was approved by the Imperial Council on July 22, 1920. It was signed on Tuesday, August 10, 1920, by representatives of the Allied and Ottoman governments.

With the Treaty of Sevres, which consisted of 433 articles (iii), only a small area in Central Anatolia was left as Ottoman territory (on the condition that Istanbul would be left to the Turks). Two new states (Kurdistan and Armenia) were planned to be established in eastern Anatolia, apart from Istanbul, Eastern Thrace would be given to Greece and İzmir would be left to Türkiye but would be governed for five years by a governor appointed by Greece, after which a plebiscite would be held, Ottoman lands such as Arabia and Iraq would be handed to Britain, Urfa, Antep, Mardin, and Syria to France, and the area south of a line from Adana to Kayseri would be under Italian control. An Armenian state would be established in the area covering Van, Erzurum, Bitlis, and Trabzon; its borders would be determined by U.S. President Wilson as arbitrator. The Dodecanese Islands would go to Italy, and other islands in the Mediterranean would be ceded to Greece. The treaty also included the establishment of a commission to manage the Straits and the continuation of capitulations.

However, the treaty never became valid, as it was not ratified by the suspended Ottoman Parliament. On August 19, 1920, the National Assembly convened in Ankara rejected the Treaty of Sèvres and declared those who signed or approved it to be traitors. Thus, the treaty was stillborn.

Meanwhile, on November 7, 1920, the Armenians, defeated by the Turkish army, requested peace. In line with the Treaty of Sèvres, U.S. President Wilson, acting as arbitrator, defined the Armenian border. However, on December 2, 1920, with the signing of the Treaty of Gümrü, the Armenians ceded Batum, Sarıkamış, Kars, Ağrı, Erzurum, Artvin, Oltu, and surrounding areas to Türkiye.

After the fall of Venizelos in Greek elections and the victory of King Constantine, Italy and France began to support Türkiye against Greece and demanded the revision of the Sèvres Treaty and Greece’s withdrawal from İzmir and Eastern Thrace during the London Conference that began on February 21, 1921. In response to this sudden shift, Britain tried to maintain a more neutral stance, but Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon advised that Britain should follow a policy that would lead to Greece’s defeat without bearing any responsibility. The tide had begun to turn in Türkiye’s favor.

The Treaty of Lausanne

Whether the Treaty of Lausanne, signed by the representatives of the Allied Powers and the Turkish state, was a victory against enemies or a necessity remains just as important to determine today as it was at the time. The explanation of what was gained is often reduced to the argument, “let’s appreciate what we have,” by bringing up the stillborn Treaty of Sèvres.

However, in a secret session of the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye (TBMM) on March 21, 1921, Mustafa Kemal Pasha stated: “The TBMM Government cannot sign a peace agreement contrary to the Misak-ı Millî (National Pact) under today’s conditions. There were obstacles to this. Because our delegation sent to London, not for a minor issue but to secure and defend our independence, holds the National Pact as its guiding principle. We said we cannot abandon this. They will defend it in front of the whole world…” With this statement, he declared the National Pact as the roadmap for peace negotiations.

Returning to the matter at hand: Even before the Lausanne talks began, Batum was ceded to Georgia by the Treaty of Moscow signed on March 16, 1921, and Syria and Lebanon were ceded to France by the Ankara Agreement signed on October 20. These hastily made agreements, contrary to the National Pact, primarily aimed to gain international recognition for the Ankara government.

Following the decisive Turkish victory against Greek occupation forces at the Battle of Dumlupınar on August 30, 1922, the Armistice of Mudanya was signed on October 11, 1922, between Türkiye and the three Allied Powers; Britain, France, and Italy.

After the armistice, both the Ankara Government and the Istanbul Government were invited to the peace conference to be held in Lausanne, Switzerland, on November 20, 1922. In response, the Parliament in Ankara abolished the sultanate on November 1, 1922. Thus, the Ankara government became the sole legitimate representative of Türkiye and participated in the Lausanne negotiations with a delegation led by İsmet İnönü. The delegation’s roadmap, as mandated by Ankara, was to realize the National Pact.

İsmet İnönü, the head of the delegation, did not possess the knowledge or capacity to lead such an extensive international diplomatic negotiation. By his own admission, his selection was due to his loyalty to Mustafa Kemal. Furthermore, the fact that the delegation’s telegram communications with Ankara were intercepted by British intelligence consistently worked against Türkiye’s interests.

During the negotiations that began on November 20, 1922, opposition emerged in Parliament against the Turkish delegation due to the concessions made from the National Pact. To suppress this opposition, an amendment was made to the Law on Treason Against the Homeland, rendering criticism of the Parliament and the government a crime of treason. The murder of Trabzon deputy Ali Şükrü Bey in March 1923, who had accused the Lausanne delegation of betraying the National Pact, intimidated and silenced opposition deputies.

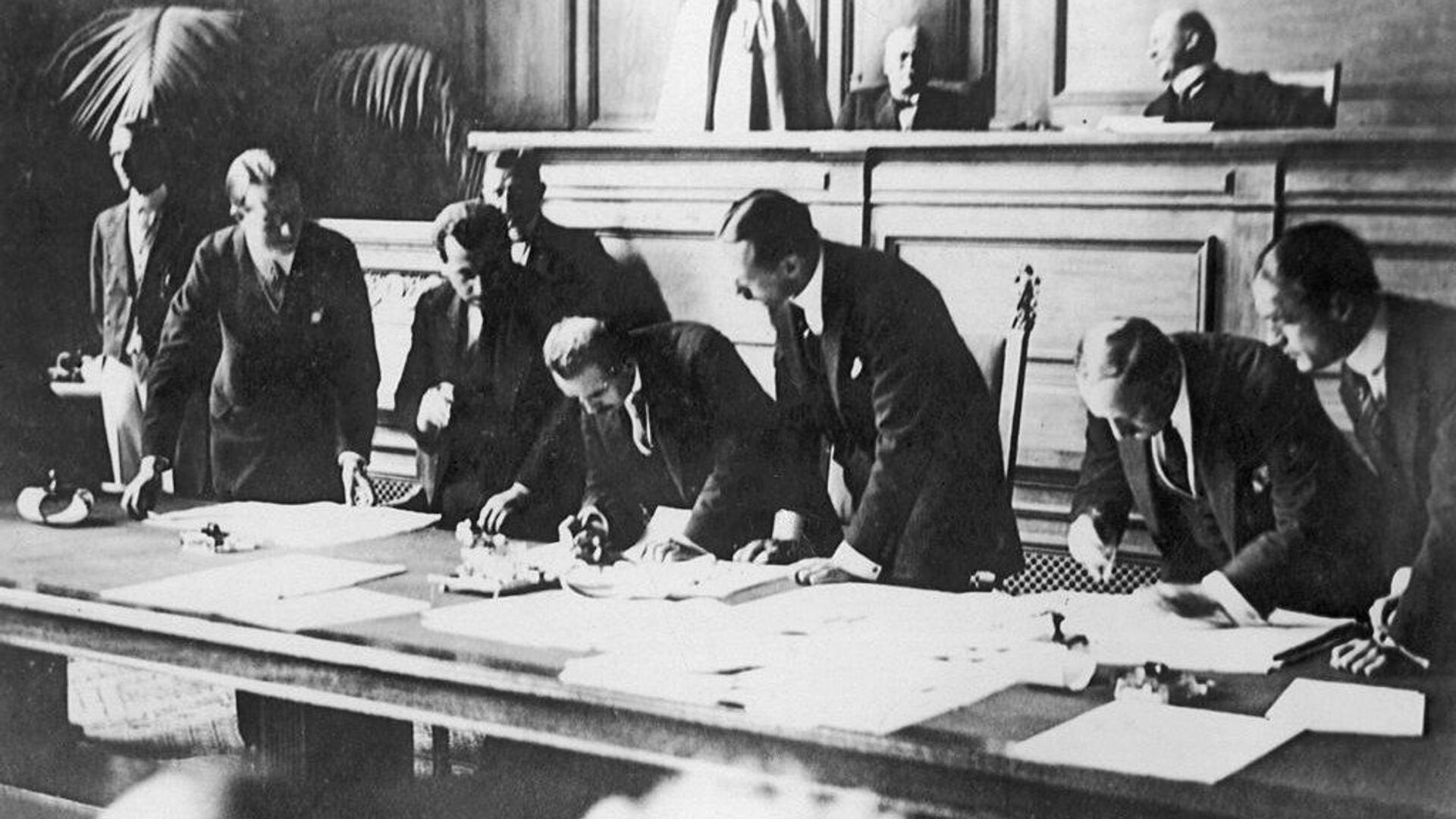

Ultimately, after eight months of negotiations, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed on July 24, 1923. Since the Council of Ministers did not authorize İsmet İnönü to sign the treaty, Mustafa Kemal personally authorized him in his capacity as Speaker of the Parliament and Commander-in-Chief.

In the peace conference convened to realize the National Pact, key regions such as Mosul, Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah, Aleppo, Hatay, Western Thrace, and the Dodecanese were left outside the borders of the Turkish state. Although Türkiye took the presidency of the international commission managing the Straits, it did not gain the right to station troops there. Article 16 of the Treaty of Lausanne stipulated that Türkiye renounced all rights and claims to territories outside the borders defined in the treaty. The abolition of the capitulations was perhaps the delegation’s only success.

It was evident that the First Parliament would not approve the Treaty of Lausanne. The Parliament was dissolved, and elections were called on April 1, 1923. The Assembly, which was formed in the elections held on 28 June 1923, in which the majority of the opposition was excluded from the Assembly, approved the Treaty of Lausanne (iv) on 23 August 1923. Following its ratification, the British withdrew their troops from Istanbul on October 2. Subsequently, Ankara was declared the capital on October 13, 1923, and the Republic was proclaimed on October 29, 1923. Any public discussion or criticism of Lausanne was forbidden. On March 3, 1924, the Caliphate was abolished, and all members of the Ottoman dynasty were exiled.

Britain was the last country to ratify the treaty. It waited until the issue of Mosul was referred to the League of Nations and approved the treaty on the same day, August 6, 1924.

While other defeated states signed peace treaties within about a year, the Turkish state had to wait six years. There must have been a reason for this delay.

A Very Special Message Sent by Lord Curzon to Mustafa Kemal in 1919

The answer to why it took six years to make peace with Türkiye lies in a message sent by Lord Curzon, who served as Britain’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs from 1919 to 1924, to Mustafa Kemal. (v)

Lieutenant Colonel Rawlinson, the British officer officially responsible for ensuring Türkiye’s compliance with the Armistice of Mudros, was tasked by Lord Curzon with establishing unofficial, non-binding contact with Mustafa Kemal before departing London on October 20, 1919.

In a meeting held before his departure, Curzon instructed Rawlinson to, if possible, meet Mustafa Kemal again and inquire under what conditions Türkiye would agree to peace, and whether Mustafa Kemal was open to a peace settlement beyond the terms declared in the Erzurum Congress Proclamation. (Rawlinson, A., Adventures in the Near East (1918–1922), Andrew Melrose Ltd., London & New York, 1924, pp. 251–252.)

In December 1919, upon returning to Erzurum, Rawlinson met with Kazım Karabekir and conveyed Lord Curzon’s message to Mustafa Kemal on behalf of the British government.

Kazım Karabekir informed Mustafa Kemal Pasha of this meeting with an encrypted telegram titled, “Confidential. Erzurum: 29/12/1335. To His Excellency M. Kemal Pasha. It is requested that this be kept extremely confidential.” (Kazım Karabekir, İstiklal Harbimiz, Türkiye Yayınevi, Istanbul 1960, pp. 414–417.)

The lengthy meeting can be summarized as follows. In his message, Lord Curzon stated that a peace agreement had not yet been signed because they could not see a strong government in Türkiye, that the current government in Istanbul lacked the necessary strength, that they saw Mustafa Kemal Pasha as the one who deserved the nation’s trust, and that they deemed it necessary for Mustafa Kemal to attend the Peace Conference.

In his message, Curzon stated that the most powerful parties in England were strongly in favor of preserving Türkiye’s existence and ensuring its independence, that they believe the peace in the British colonies in Asia could only be achieved by achieving Türkiye’s independence, that the British government also accepted this, that the England would not allow other powers to partition Türkiye, that British public opinion had now turned against the Greeks and that they would expel the Greeks from Izmir, that it was impossible for the Armenians to establish a government on Anatolian soil, that England would work to preserve Türkiye’s existence, ensure its independence, and foster its economic development.

After enduring many sacrifices, Lord Curzon expressed in his message that they were worried that Türkiye might one day side with the enemies of England, and that because of this concern, England wanted to make an agreement with people who would be true friends of England in Türkiye, and that these people should of course be people who had influence over the Turkish nation, and that they wanted to get “guarantees” from people who would be true to their word and would not act against England when the opportunity arose in return for good deeds done on behalf of the nation.

Through Rawlinson, Lord Curzon also inquired about Mustafa Kemal’s views on separating the Caliphate from the Sultanate, transitioning to a republic, and relocating the capital from Istanbul. According to him, since Türkiye had withdrawn from Rumelia (the Balkans), it had become an Asian state, and governing Anatolia from Istanbul was no longer feasible; thus, the capital should be relocated.

Mustafa Kemal Pasha responded to Kazım Karabekir’s telegram dated December 29, 1919, with a cipher dated January 8, 1920. In this telegram, Rawlinson was invited to come to Ankara if he had the authority to negotiate on behalf of his government. (Karabekir, Kazım, ibid., pp. 417–418)

However, the expected meeting never occurred, as Rawlinson lacked formal authority to negotiate on behalf of the British government.

Later, it is seen that whatever Lord Curzon wanted in the message he sent to Mustafa Kemal Pasha came true. On November 1, 1922, the Caliphate and Sultanate were separated; on October 13, 1923, the capital was moved to Ankara; on October 29, 1923, the Republic was declared; on March 3, 1924, the Caliphate was abolished. Following the fulfillment of all demands, Britain ratified the Treaty of Lausanne on March 6, 1924.

This clearly shows that someone with the authority to negotiate on behalf of the British government had been assigned and that backdoor diplomacy was at work.

Are There Secret Clauses in the Treaty of Lausanne?

Lord Curzon personally represented and led the British delegation during the first phase of the Lausanne negotiations, held between November 20, 1922, and February 4, 1923. İsmet İnönü, the head of the Turkish delegation, was known as a loyal diplomat directly authorized by Mustafa Kemal Pasha.

As early as 1919, Lord Curzon, who had sought backdoor negotiations with Mustafa Kemal, pledged that Britain would work toward the preservation of Türkiye’s existence, the securing of its independence, and its economic development. After eight months of negotiations, the Allied Powers ultimately received everything they wanted. All that remained for Türkiye was the consolation of having abolished the capitulations.

Given that all the requests mentioned in Lord Curzon’s message were fulfilled one by one, it is undeniable that a guarantee was provided to Britain to remain friendly and refrain from hostility. Even this narrative alone reveals that the Lausanne negotiations were not transparent and that additional commitments existed beyond the treaty that was signed.

Whether the Treaty of Lausanne, presented as the founding charter of the Republic of Türkiye, contains unpublished clauses will become clearer in the future.

However, when we examine the radical Western reforms imposed shortly after the signing of this so-called founding agreement, such as the restructuring of the state, the constitutional order, the alphabet reform, the abolition of the Caliphate, the adoption of Western legal codes, and the dress code laws, it is difficult to believe that such drastic changes and transformations were fully initiated and prepared by Türkiye’s own will.

Indeed, in the third article of the telegram mentioned above, Kazım Karabekir Pasha expressed his personal opinion regarding Lord Curzon’s demands as follows; “I would like to express my respects and state that the caliphate and the sovereignty cannot be separated, that a republican administration cannot be established in our country, that the central government cannot be transferred to any district other than Istanbul, and that our nation cannot be prepared to accept any contrary to these.” Even Kazım Karabekir, who was among the leaders of the national movement, did not see these changes as possible.

The need for revolutionary laws that aim to fundamentally change our society, and the basis on which the Ottoman state would be completely eliminated and a new state in Anatolia compatible with the nature of the West would be established, have always been questioned, and will continue to be questioned. That is, until our current state authority or future historical transformations reveal documents that clarify the truth.

It’s important to point out this: Was destroying all the values of the Ottoman Empire, which had lasted over 400 years, and establishing a new state on these lands under French, British, and Italian law, the plan of the leading elite leaders who fought to protect these lands at the cost of their lives during the War of Independence, or was it a result they achieved after eight months of pressure from Western powers?

When we look at today’s political movements, since there are secret clauses even in agreements made just to form an electoral partnership, why shouldn’t we consider that there may be additional secret clauses for the establishment of a new, small state with Western standards, with the aim of destroying and eradicating the great Ottoman Empire?

Conclusion

When considering the historical process, it can be said that many who sanctify Treaty of Lausanne and declare it untouchable do not do so out of a fear of national disintegration.

What is actually being preserved under the label of Treaty of Lausanne’s inviolability are the commitments made to Britain during the negotiations. The aim is to protect the changes made at Britain’s request and to prevent the Turkish people from turning against Britain.

For nearly a century, due to repetitive indoctrination and the sanctification of certain narratives starting from primary school, the historical memory of the Turkish Nation has been frozen, its vision narrowed, and it has been alienated from its own homeland, history, and values, and even the peoples who were once part of the Ottoman Empire have been mentally cast as enemies.

The time is approaching to break these patterns and re-read history properly.

Footnotes

[i] Mustafa BUDAK, I. Dünya Savaşı sonrası yeni uluslararası düzen kurma sürecinde Osmanlı Devleti’nin tavrı

https://www.divandergisi.com/pdf/63.pdf

[ii] Misâk-ı Millî ve Misâk-ı Millî Haritası

https://www.ttk.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Misak-i-Milli-Uzun-Metin.pdf

[iii] Sevr Andlaşması

https://ttk.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/6-Sevr.pdf

[iv] Lozan Andlaşması

https://ttk.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/3-Lozan13-357.pdf

[v] Sinan TAVUKCU, İngilizler ve Erzurum Kongresi

https://sinantavukcu.com/2012/10/10/ingilizler-ve-erzurum-kongresi/

Source: https://www.sde.org.tr/sinan-tavukcu/genel/lozan-antlasmasinin-kutsiyeti-var-mi-kose-yazisi-34576