We all have a smart device in our hands, sometimes typing, sometimes speaking. We use our index fingers so much to press the buttons on these smart devices that our brains are baffled by the situation. Probably, the brains of future generations will allocate more space to the index finger. Taking photos and having them taken has become quite a mundane activity. Even the least privileged among us have more photos than any celebrity would have had in their album 20 years ago. If someone were observing us from space and tried to describe our current state, they would begin their sentence with: “They each have a device—except for their biological limbs—that they never let go of, constantly look at, occasionally bring to their ears to talk, and try to record everything they see with.”

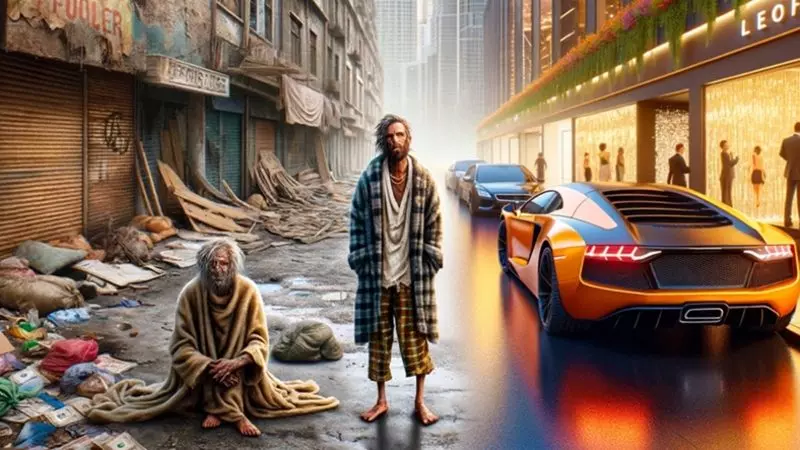

Yes, children and adults, young and old, women and men—we are all like this. So much so that some even go so far as to say, “There is no difference between rich and poor in this regard; our lifestyles have become identical, converged.” Similar to past claims that the media ensured the equal distribution of information and contributed to democratic awareness, such arguments are now being made for technology. But is that really the case? Are we mistaken in thinking and asserting that the gap between the wealthy North and the impoverished South has begun to widen to a chasm, and that the rich have completely written off the poor in their quest for eternal life?

We Need a Hard-Working Local Academy!

Let us read together the following lines written in the introduction of the book Tastes: Reflections of Social Change in Everyday Life, published by İlem Yayınları and edited by Professor Lütfi Sunar—whose work I greatly admire and follow with appreciation, especially his sociological research on social stratification:

“In recent years, cultural stratification seems to have diminished due to technology. While cultural distinctions still exist in terms of the enlightened, the semi-cultured, and the uncultured, people from different backgrounds or classes can come together thanks to the internet and especially social media, and people from all strata can access the same cultural products or information…”

These statements inevitably give the impression of a positive reference to the technomedia world. But that is not the case, for two reasons. First, the trajectory is not toward the better, but the worse. As Professor Sunar states, “Today, with increased and widespread contact with technology, we are in a world not of those who look at the shop window, but of subjects who carry themselves into the shop window,” as everyone talks about this phenomenon of “change and transformation.” The consumer society turns us all into part of the spectacle.

The second reason is that, contrary to popular belief, technology does not eliminate the rich-poor divide. The fundamental factors determining socio-economic status—education, income, and occupation—remain the same today as they did in the past. This is clearly evident in the articles in the aforementioned book, and especially in the findings of the research conducted by Professor Sunar and his team in 2014 aimed at developing a Socio-Economic Status (SES) Index in Türkiye.

In their research, Sunar and his colleagues conclude that, contrary to what is commonly believed, there is a marked distinction between social classes in Türkiye in terms of consumption and lifestyle. Looking at activities such as dining out as a family, attending cinema/theatre/sports or concert events, going on vacation, and exercising regularly, a clear difference between social strata becomes apparent. Even in family structures, lower and upper SES groups diverge—while the poor live in extended families, the upper SES groups have begun transitioning from nuclear families to single-person households.

When examining media usage preferences and internet usage, a marked difference is also noticeable between lower and upper SES groups, rather than a resemblance brought about by technology. The poor spend almost all of their free time watching television. They also gather with friends and frequently visit relatives and elders, but even during these times, most of their time is likely spent in front of a screen. They watch TV series and the news. Interestingly, upper SES groups listen to the radio more. This is probably largely due to the time they spend in their cars. As people’s position in socio-economic stratification rises, so does their rate of internet use. There is even a difference between lower and upper SES groups in terms of social media accounts. No difference is observed among Facebook users, but the number of people with Twitter (X) and Instagram accounts increases as SES levels rise. In short, the research clearly shows that socio-economic status continues to determine preferences, cultural tendencies, and lifestyle.

We Need More Courageous Sociologists Like Bourdieu

This research did not take into account upward mobility, conservative tendencies, or levels of religiosity. Had these been considered, a reality we have all observed over the last quarter-century would have come to light: those newly joining the upper classes through access to power would be seen to have adopted and replicated the very lifestyles they once criticized—except for a few minor religious adjustments. We would have been horrified to realize that it is not faith shaping lifestyle, but lifestyle shaping the way people believe, and that astonishingly rapid transformations have occurred in religious interpretation. In truth, we don’t even need surveys or research findings to know this; we already see and perceive it. The members of the upper classes may change, but the upper-class attitude remains exactly the same.

To discuss all of this, we need a solid sociological perspective and research that examines the links between economic capital and social and symbolic capital, class and lifestyles, visible and invisible forms of domination, the state, the school, language, and the media. We need studies like those conducted by Pierre Bourdieu and his team in the 1990s, who traveled throughout France to paint a near-complete picture of the poverty experienced there (as documented in The Misery of the World). Of course, such research requires a phenomenological method and perspective—one that is free from theoretical and ideological biases and capable of turning the lens inward.

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu was right when he said that different social classes exhibit different cultural tendencies—workers being interested in football or boxing, while the bourgeoisie is inclined toward tennis. In my view, Bourdieu was right not only when he emphasized the role of social class in tastes, but also when he identified education as a primary driver in this context. Even school curricula are designed according to the cultural codes of the middle and upper classes, while the lower classes are consistently segregated from the rest of society. Inequalities between classes are continually reproduced through education. And the striking thing is that the poor have no intention of questioning why this is the case…

Last year, when the LGS (High School Entrance Exam) results were announced, my heart sank. The exam system and the style of the questions may be open to criticism, but in the end, many top scorers emerged. Although many of our children answered all the questions correctly, those coming from public schools were unable to gain admission to their desired schools due to tiny differences in school performance scores. Unfortunately, this staggering inequality barely made the news. And yet, it was an unmistakable harbinger of catastrophe—one that surfaced in a period when justice was being sought, under the rule of a party named Justice. To my knowledge, there is not a single scientific study on the worsening class disparities in our education system; the state is increasingly ceasing to be “the protector of the orphaned.”

Thus far, we have expressed our views based on segments that are visible and empirically researchable. I have not yet revealed what’s truly on the tip of my tongue. The answer to the question posed in the title of this article—“Does technology eliminate the rich-poor divide?”—now seems quite obvious. On the contrary, the divide between rich and poor is growing ever wider. A new subaltern class is emerging, unlike anything seen in human history: a useless, virtually “excess” mass. Marx referred to the lumpen proletariat as “social dregs.” These new subalterns are not even dregs—they are outright waste, bile waste… I fear that with the rise of technology, robots, and artificial intelligence, the richest are attempting to turn everyone else into waste, to design the world (and perhaps even space) solely for themselves. I always say: modernity is not, as is commonly believed, human-centered—it is, in fact, an entirely anti-human civilization.