Source: DÎVÂN Journal of Scholarly Studies Issue 15 (2003/2), pp. 1–51

The Story of the Formation of the Perception of Islam in Eastern and Western Christianity During the Middle Ages

The negative consequences of September 11 led the long and winding relationship between Islam and the West into a new phase. In many European countries and in American public opinion, a widespread and explicit climate of suspicion about Islam prevailed. The attacks were interpreted as the fulfillment of a prophecy long embedded in Western consciousness, that Islam would one day sharpen its teeth and move to destroy Western civilization. The idea that accept Islam unjustly as an oppressive religious ideology, and regard Islam unjustly as pro-violence and terrorism has become a widespread discourse, and everything from television screens to government offices, from schools to the internet has become a tool for expressing opinions and passing judgment on this issue. This radicalized image of Islam in people’s minds brought forward the idea of developing an offensive against religious conservatism and terrorism. Some even proposed launching a nuclear attack on the Muslims’ holy city of Mecca as a way to teach the world’s Muslims an unforgettable lesson. The widespread anger, hostility, and desire for revenge could be interpreted as a human reaction to the loss of nearly three thousand innocent lives. However, its connection to portraying Islam and Muslims as demonic beings, rests on much deeper philosophical and historical foundations.

From the theological polemics that emerged in Baghdad in the 8th and 9th centuries, to the convivencia (coexistence) experience in Andalusia in the 12th and 13th centuries, many factors have shaped the ways in which the two civilizations perceived each other and the suspicions they harbored. This study will examine the most important elements that stand out in the history of the relationship between the West and Islamic civilization, and will argue that the roots of the monolithic conception of Islam, which has been created and maintained by the media, research institutions, academic circles, lobbies, policy designers and image makers that control Western consciousness, lie in the West’s long history with Islam. It will also highlight how deeply rooted suspicions about Islam and Muslims have played a role in fundamentally flawed political decisions that directly affect current relations between the West and Islam. The prejudice that emerged in the minds of many Americans after September 11th, that Islam is almost identical to terrorism and extremism, points to both a misperception of history and to the fact that some interest groups see reckoning with the Islamic world as the only way out. This study seeks to provide a historical framework that will help us understand the developments after 9/11 and their reflections in both civilizations.

Two main attitudes stand out in the West’s perception of Islam: the first and, until now, the most widespread view is that of incompatibility and conflict. Its origins go back to the 8th century, when Islam emerged on the stage of history and was quickly perceived by the West as a theological and political threat to Christianity. In medieval European thought, Islam was seen as a heresy and the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) as an impostor. This idea forms the religious foundation of the conflictual stance that has extended to the present and gained momentum after 9/11. In the modern period, this conflictual attitude combined both religious and secular terms. The most well-known of these is the “clash of civilizations” hypothesis, which emphasizes political and strategic interests between Muslim and Western countries in the context of deep religious and cultural differences. The second view is that of “coexistence and compromise,” which, although historically supported by Swedenborg, Goethe, Henry Stubbe, Carlyle, and others, has only become a major alternative in the past decade. Those who support the reconciliation view, see Islam as a sister religion and argue that since it is in fact part of the Abrahamic tradition, the possibility of Islam and Christianity coexisting will increase, as in the examples of Swedenborg and Goethe. This view, which we will briefly address in the final part of the study, marks a new and important turning point in the history of Islam and the West by emphasizing long-term coexistence and mutual understanding.

The first part of our study will focus on how Islam was initially perceived by Christian theologians, first in the East and then in Europe, as a religious heresy. The roots of common views such as Islam being a religion of the sword, Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) being a violent figure, and the Qur’an being a meaningless theological text all go back to this period. The second part will address medieval and Renaissance’s perceptions of Islam, that regarded Islam, in contrast to Christianity’s intellectual and religious superiority, perceived as a world culture. Although some late medieval and Renaissance thinkers evaluated Islam in the same way as other religions and ridiculed it by claiming it to be irrational and false like others, they did not refrain from appreciating the philosophical and scientific developments that Islamic civilization had made. This new stance played an important role in shaping 18th- and 19th-century European perceptions of Islam. It also paved the way for the rise of Orientalism, which produced official studies on the East and Islam in the following two centuries. In the third part, we will discuss Orientalism within the framework of the West’s perception of Islam, and how Orientalism shaped the modern Western perception of Islam. After drawing a sufficient historical framework, the final part of the study will provide more detailed information on how the accusations of violence, terror, aggression and fundamentalism used to emphasize the bellicose image of Islam as the “other” were associated with the perception that Islam was a religion of the sword in the late Middle Ages. It will also argue that the fundamentalist narrative of Islam has largely misinterpreted and militarized the concept of dār al-ḥarb in opposition to jihad and dār al-Islām, in order to block the possibility of forming a discourse of dialogue and coexistence between Islam and the West.

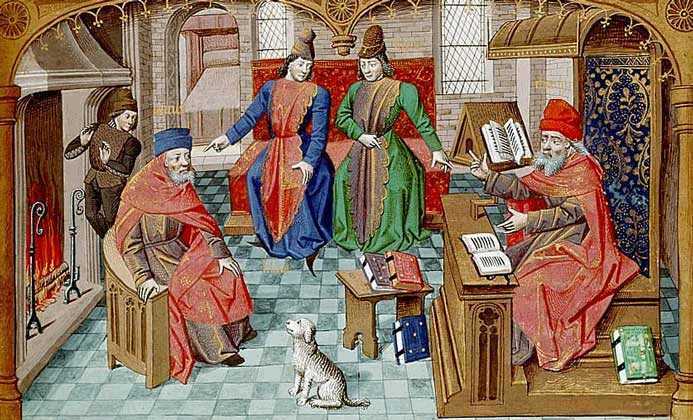

From Theological Rivalry to Cultural Difference: Perceptions of Islam Throughout the Middle Ages

Islam, which claims to be the last of the Abrahamic and divine religions, was from the beginning regarded as the greatest challenge to Christianity. References to Jewish traditions and Christian prophets, hadiths, prophet stories in the Qur’an, and some other matters were sometimes in harmony and sometimes inconsistent with the biblical texts. This contributed, on one hand, to feelings of bewilderment and distrust in the Christian world, and on the other, to the urgency of responding to Islam’s claim to originality. The earliest polemics between Muslim scholars and Christian clerics reveal how eager both communities were to defend their faiths. Between the 8th and 10th centuries, Baghdad and Syria became two major centers of intense intellectual exchange and theological polemics between Muslims and Christians. Although theological rivalry continued, there was also considerable exchange in philosophy, logic, and theology beyond polemical disputes. Eastern Christian theologians had the opportunity to pose a serious challenge to Muslim theologians, as they were one step ahead of Muslim thinkers in developing a comprehensive theological language using knowledge from ancient Greek and Hellenistic cultures. The key point here is this: Islam was perceived as a religious challenge to Christianity not because it was entirely different or a brand-new religion. On the contrary, even though the Qur’an criticized certain Jewish and Christian beliefs, Islam’s message shared significant common ground with both Judaism and Christianity.

Another important factor was the rapid expansion of Islam into regions previously under Christian control. A century after the conquest of Mecca, Islam spread beyond the Arabian Peninsula, from Egypt to Jerusalem, from Syria to the Caspian Sea and North Africa, and many people living in these regions converted to Islam. As People of the Book, Jews and Christians were granted religious freedom under Islamic law and were not forced to convert. This unexpected rapid expansion of Islam was enough to alarm the Christian West. The Crusades that were launched a few centuries later were rooted in this very fact. Added to this was the advance of Muslim armies towards the West, first under the Umayyad, then Abbasid and finally Ottoman banners, and this increased the concerns in the West and these concerns continued until the decline of the Ottoman Empire, which was the leading political power in the Balkans and the Middle East. Two main reasons were often cited for Islam’s rapid spread: that it spread by the sword, and that the Prophet appealed to men’s animal instincts through polygamy and concubinage. As 17th-century traveler George Sandys noted, later this list was expanded to include the simplicity of the Islamic faith, and thus converts to Islam were disparaged as “simple-minded” in a quasi-racial sense.[1]

On the one hand, the theological foundations of Islam as a religion, and on the other hand, the expansion of Islamic lands in such a short time, played an important role in the formation of anti-Islamic sentiments in the Middle Ages. No one illustrates this situation better than Saint John of Damascus (675–749), known in Arabic as Yūḥannā al-Dimashqī and in Latin as Johannes Damascenus. Like his father Ibn Manṣūr, John served as a court official to the Umayyad caliph in Syria. John is significant not only because of his contributions to Orthodox theology and his fight against iconoclasm in the 8th century but also because of the vital role he played in the historical development of Christian polemics against Muslims, then commonly referred to as “Saracens.” It seems that the derogatory term “Saracen,” used in many later anti-Islamic polemics, goes back to John.[2] Along with his contemporary Bede (d. 735) and a generation later Theodore Abū Qurra[3] (d. 820/830), John of Damascus shaped the character of medieval perceptions of Islam with the claim that Islam was in fact a deviation from Christianity or, in his own words, “a heresy of the Ishmaelites”[4], determined, for Christians, the nature of the understanding of Islam in the Middle Ages and this understanding continued to be the most determining element in this field until the end of the Renaissance.[5] Many of the theological depictions that portrayed Islam as an illusion of the Ishmaelites and a herald of the Antichrist[6] stemmed from Saint John. Moreover, he was the first Christian polemicist to accuse the Prophet of being a false prophet: “The founder of Islam, Muhammad, was a false prophet who stumbled upon the Old and New Testaments by chance. He also pretended to encounter an Arian monk in order to concoct his own heresy.”[7]

One important point about John’s polemics is that, unlike most of his Western successors, he had direct knowledge of Muslim ideas and language.[8] R.W. Southern made a very accurate observation when he called the lack of first-hand knowledge of Islamic beliefs and practices by Christians throughout the Middle Ages “the historical problem of Christianity” in order to prevent the sprouts of heresy from growing in their religion and to take the necessary precautions in this regard.[9] The lack of direct contact and reliable sources of information led to the emergence of a false history of Islam and the Prophet Muhammad in the West. This resulted in Islam being a formidable enemy in European consciousness throughout the Middle Ages. This problem combined at a later stage with the Byzantine struggles against Islam and the hostile literature, generally on theological grounds, produced by Byzantine theologians between the 8th and 10th centuries. The anti-Islamic Byzantine literature, while presenting specific criticisms of certain verses of the Qur’an regarding Islamic belief and practices[10], perceived Islam as a theological rival and labeled it as heresy, displayed remarkable first-hand knowledge, providing a good historical and theological basis for later criticisms of Islam.[11]

Just as deliberate ignorance was a subtle strategy of the time, so too was the perception of Islam as a theological challenge that had to be categorically rejected. The Qur’an’s rejection of the trinity in favor of monotheism, its view of Jesus as a prophet rather than divine, and its emphasis on religious communities existing without clerical hierarchy or church authority did not escape the notice of Western Christianity. Unlike Eastern Christianity, which was located in the middle of the Muslim world and had easier access to information about Islam, Islam in the West was seen as nothing more than a base form of heresy and idolatry, and even less than the Manichaean religion, to which St. Augustine belonged before converting to Christianity. Unlike the example of Spain, where the three Abrahamic religions coexisted for a considerable period of time and engaged in cultural and intellectual exchange, the vacuum created by Western Christianity’s spatial and intellectual limitation was filled with many fabricated stories about Islam and Muslims. These invented tales were further reinforced by the Crusaders, who brought back new imaginary stories, legends, and figures.

One might have expected the Crusaders to bring back more reliable and accurate information about Islam, but this did not happen. Instead, they returned with depictions that reinforced the notion of Islam as a godless, idolatrous faith. Yet, the Crusades did yield an important result not often acknowledged in accounts of medieval Western perceptions of Islam. As the first Western Christians to penetrate deep into the Islamic world, the Crusaders encountered Islamic cities, roads, markets, mosques, and, most importantly, its people. When they returned, they did not bring only the legend of Saladin, the conqueror of Jerusalem, and luxury goods like silk, paper, and perfumes, they also brought the Muslim lifestyle, the idea that they were sensual and wealthy, to Western Europe. In addition to these widespread imaginations, these stories and imported products that reached the West and pointed to the indulgence in luxury in worldly life also supported the Western idea of how “evil-natured” the “Ismaili” (Arab) heretics were. These stories, while sometimes accompanied by a hidden admiration, did little to improve Islam’s image in Western minds. Nevertheless, they opened a new door for perceiving Islam not only as a religion but also as a culture and civilization. In this way, Islam, which was constantly denigrated on a religious and theological level, gained a neutral value as a culture, even though it had no importance on its own, the importance of this change of perception cannot be emphasized enough. After the 14th century, as Christianity began losing its grip in Western society, many outside the clergy who no longer cared about traditional Christian critiques of Islam referred to it as a noteworthy cultural and civilizational sphere beyond Christianity’s theological and geographical boundaries. Strangely enough, Islamic civilization as it was known in Western Europe was set up as an example against Christianity in order to reject its claim that it was the only true and universal truth. This helps explain Renaissance Europe’s stance: the Renaissance despised Islam as a religion but admired it as a civilization.

During the bloody and ambitious Crusades, an important and unexpected development occurred in the literary engagement with Islam. For the first time in history, the Quran was translated into Latin with the support of the Christian theologian Peter the Venerable (d. 1156). The translator was Robert of Ketton. Robert completed his unfinished work in July 1143.[12]

For the first time in history, the Qur’an was translated into Latin. With the support of Peter the Venerable (d. 1156), the translation was undertaken by Robert of Ketton, who completed his work in July 1143. As expected, the main motive for translating the Qur’an was not to understand Islam by reading its holy book but to know the “enemy” better. Peter explained his reasons as follows:

“If this work seems unnecessary, let me say within the supreme Republic of the Kingdom that since the enemy cannot be easily wounded by such weapons, some things are for defense, some for adornment, and some for both. Peaceful Solomon prepared armies for a defense that was unnecessary in his time. David adorned the Temple with ornaments that had little meaning in his own time (…) Likewise, this work, even if it cannot convert Muslims from their religion, will at least provide learned men with a defense against weaker brethren in the Church who are displeased by trifles.”[13]

If we leave aside the main purpose behind the translation of the Qur’an, it must be said that this is a very important development. This translation shaped the direction and scope of studies on Islam in the Middle Ages, and provided those who criticized Islam with the opportunity to criticize it through a single text and to find a basis on which to base most of their expected criticisms.[14] Even more significant than the translation itself was the inclusion of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) into the anti-Islamic framework of medieval Christian thought. Although St. John of Damascus was the first to call the Prophet of Islam a “false prophet,” we do not find references to the Prophet known as “Mahomet” as a significant figure in anti-Islamic literature before the 11th century. However, with the inclusion of the Prophet Muhammad in this picture after the translation of the Qur’an, a new and eschatological dimension was added to the presentation of Islam as a guilty and evil religion, for which the judgment had already been given, as the Prophet of Islam could be identified with the antichrist who heralded the end of the world.

This depiction of the Prophet of Islam is equally affected by the same historical problem of medieval Europe that we have already mentioned, namely, the lack of Islamic knowledge based on original sources, texts and reliable dates. Indeed, until the late 13th century, none of Islam’s Latin critics knew enough Arabic. The scholastic philosopher Roger Bacon complained that King Louis XI of France could not find anyone who could read and translate an Arabic letter sent by the Sultan of Egypt, nor anyone to compose a reply in Arabic.[15] Arabic was not formally taught at any European university until the late 16th century. Only in 1587 did regular Arabic courses begin at the Collège de France in Paris. The first Latin biography of the Prophet, Vita Mahumeti, written by Embrico of Mainz (d. 1077), selectively drew on Byzantine sources and presented crude depictions of Prophet Muhammad’s (pbuh) private and social life.[16]

The picture that emerged after such studies, namely the Prophet of Islam and his dissemination of this new belief in a way that would disturb some, largely coincided with the apocalyptic theories based on the emergence of the antichrist, the promise of which is given in the Holy Book. As might be expected, the theological concerns of this period did not allow for reliable scholarly work to be conducted for the next two centuries and for a more positive image of the Prophet to emerge.

Almost all Latin works on the life of the Prophet up to the present had a single aim: to prove that someone like Muhammad could not possibly be a prophet of God. The unchanging theme was the contrast between Muhammad’s “worldly” qualities and Jesus’ “spiritual” nature. According to the Latins, Muhammad was obsessed with sexual desire and political power, which he used to control his followers and harm Christianity. He was ruthless toward his enemies, especially Jews and Christians, and took pleasure in torturing and killing those who opposed him. The only logical explanation for his religious and political success, they argued, was that he was a sorcerer who used magical powers to persuade people to convert. Such views of Prophet Muhammad’s psychological state persisted in Europe until the late 19th century. For example, William Muir (1819–1905), a British colonial officer in India and later administrator at Edinburgh University, described Muhammad as a “psychopath” in his polemical book Life of Mohammed, echoing medieval critics. Myths proliferated that he had a Christian background, that his corpse had been eaten by pigs, that his sanctity was defiled, or that he had secretly been baptized before his death as a final attempt at salvation.[17]

This image of the Prophet can be seen as an extension of unequivocal denials of the Qur’an as genuine revelation. In fact, since the Prophet Muhammad was portrayed as a madman with a hallucinatory spirit, it was more convincing in the eyes of the opponents of the Quran to be attached to such a man named Muhammad. There is also a deeper theological reason for focusing on the figure of the prophet. Because Christianity was fundamentally a “Christian” religion and Jesus was seen as the incarnation of God’s word, Latin critics saw the same role for Muhammad within the Islamic religious worldview: Islam could not be understood or rejected without its prophet. The rejection of the Qur’an as divine revelation, combined with the portrayal of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) as a deluded sorcerer, continued to shape Western perceptions of Islam well into the modern era. Perhaps the most disturbing result of this was Islam’s exclusion from the family of monotheistic religions. Despite the tripartite dialogue that has come to the fore in the modern era between Judaism, Christianity and Islam as a result of the endless perseverance of scholars such as Sayyed Hossein Nasr, Ismail Raji al-Faruqi, Kenneth Cragg and John Hicks[18], it is clear that Islam, like the other two Abrahamic religions, has been included in the monotheistic religious universe and that it is still not possible to confidently speak of a Judaeo-Christian-Islamic tradition by placing it in the same category as them. The absence of such a discourse strengthens the medieval perception of Islam as a perverse and idolatrous religion and prevents Islam from being evaluated on a more comprehensive basis on religious levels.

[1]These commonplace explanations for the spread of Islam were accepted even among 19th-century American writers such as Edward Forster, John Hayward, and George Bush, the first American to write a biography of the Prophet; see Fuad Sha’ban, Islam and Arabs in Early American Thought: The Roots of Orientalism in America, The Acorn Press, North Carolina 1991, pp. 40-43.

[2]According to Oleg Grabar, the term “Saracen” comes from the word “Sarakenoi”: “John of Damascus and others after him always insisted that the new owners of the Near East were ‘Ishmaelites’, outcasts. In this sense, the old term Sarakenoi meant “empty of Sara” (ek tes Sarras kenous), and the Arabs were referred to, often derogatorily, as Agarenois”; see Oleg Grabar, “The Umayyad Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem”, Ars Orientalis, v. 3 (1959), p. 44.

[3]For selections from Theodore Abu Qurra and his writings against Islam, see Adel-Theodore Khoury, Les Théologiens Byzantins et L’Islam: Textes et Auteurs, Editions Nauwelaerts, Louvain 1969, pp. 83-105.

[4]The term “Ishmaelites” here does not refer to Ismailism, which developed as a branch of Shiism, but to Arabs and Muslims more generally, in the sense of “descendants of Ishmael.” Christian theologians and historians used this term because they believed that Arabs were descended from Ishmael.

[5]Bede was the first theologian to classify Muslims (Saracens) as enemies of God’s biblical commandments; see Norman Daniel, Islam and the West: The Making of an Image, Oneworld, Oxford 1993 (1st ed. 1960).

[6]Daniel J. Sahas, John of Damascus on Islam: The “Heresy of the Ishmaelites,” E.J. Brill, Louvain 1972, p. 68.

[7]Quoted from De Hearesibus, 764b: Sahas, ibid., p. 73.

[8] For the career of St. John under the Umayyad caliphate, see Sahas, op. cit., pp. 32-48.

[9] R.W. Southern, Western Views of Islam in the Middle Ages, Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1962, p. 3.

[10]As Kedar points out, this is the result of Eastern Christianity’s daily contacts with Muslims; see Crusade and Mission: European Attitudes toward the Muslims, Princeton University Press, Princeton 1984, pp. 35 ff.

[11]Some of the anti-Islamic texts produced by Byzantine theologians are collected in Adel-Theodore Khoury’s Les Théologiens Byzantins et L’Islam. This work includes representative texts by theologians such as St. John the Syrian, Theodore Abu Qurra, Theophane the Confessor, Nicetas of Byzantium, and George Hamartolos.

[12]For Ketton’s translation, see Marie-Thérèse d’Alverny, “Deux Traductions Latines du Coran au Moyen Age”, Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Age 16, Librairie J. Vrin, Paris 1948. The same article also appeared in her own work; La connaissance de l’Islam dans l’Occident médiéval, Variorum, Great Britain 1994, v. I, pp. 69–131. In this work, d’Alverny also analyzed Mark of Toledo’s Latin translation, completed shortly after Ketton’s. See also James Kritzeck, “Robert of Ketton’s Translation of the Qur’an”, Islamic Quarterly, II/4 (1955), pp. 309–312.

[13]Peter quoted in Southern, op. cit., pp. 38-39. Despite his deliberate anti-Islamic campaign, Peter the Venerable inaugurated a new era in the study of medieval European Islam; see James Kritzeck, Peter the Venerable and Islam, Princeton University Press, Princeton 1964, pp. 24-36.

[14] Cf. Kenneth M. Setton, Western Hostility to Islam and Prophecies of Turkish Doom, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia 1991, p. 47-53.

[15]See James Windrow Sweetman, Islam and Christian Theology, Lutterworth, London 1955, part 2, vol. Work. 98 99. Marie-Thérèse d’Alverny also draws attention to the same problem in her important article: “La connaissance de l’Islam en Occident du IXe au milieu de XIIe siécle”, Settimane di studio del Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo 12, L’Occidente e l’Islam nell’alto medioevo, Spoleto 2-8 aprile 1964, col. II Spoleto, 1965. La connaissance de l’Islam dans l’Occident medieval, c. V, s. 577-578.

[16]See John Tolan, “Anti-Hagiography: Embrico of Mainz’s Vita Mahumeti,” Journal of Medieval History, v. 22 (1996), 25–41. Southern cites two other works of equal importance. First, Walter of Compiegne’s Otia de Machomete, written between 1137 and 1155, and second, Guibert of Nogent’s Gesta Dei per Francos, a chronicle of the Crusades compiled in the early twelfth century, which includes a section on the Prophet of Islam; see Southern, op. cit., p. 30.

[17]For more on the conception of the Prophet of Islam in the West from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance to the present, see Clinton Bennett, In Search of Muhammad, Cassell, London-New York 1998, pp. 69–92 and 93–135; Norman Daniel, Islam and the West: The Making of an Image, 100–130. For a critical assessment of the views of three orientalist scholars on the Prophet of Islam, see Jabal Muhammad Buaben, Image of the Prophet Muhammad in the West: A Study of Muir, Margoliouth and Watt, The Islamic Foundation, Leicester 1996.

[18]See Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Knowledge and the Sacred, State University of New York Press, Albany, N.Y. 1989, p. 280-308, the same writer, “Comments on a Few Theological Issues in Islamic-Christian Dialogue,” Christian Muslim Encounters, ed. Yvonne-Wadi Haddad, Florida University Press, Florida 1995, p. 457-467; the some writer, “Islamic-Christian Dialogues: Problems and Obstacles to be Pondered and Overcome”, Muslim World, p. 3-4 (July-October, 1998), p. 218-237; Kenneth Cragg, The Call of the Minaret, Orbis Books, New York 1989 (ed. 1, 1956); the same writer, Muhammad and the Quran: A Question of Response, Orbis Books, New York 1984; Ismail Raji al-Faruqi (ed.), Trialogue of the Abrahamic Faiths, International Institute of Islamic Thought, Herndon, VA 1982; Frithjof Schuon, Christianity/Islam: Essays on Esoteric Ecumenism, World Wisdom Books, Bloomington 1985.