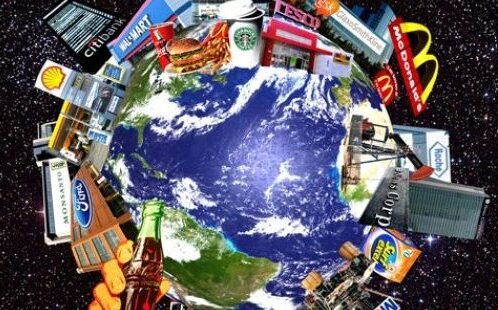

There are many characteristics that distinguish the modern era we live in from other periods of human history. One of them is its focus on consumption. In the early stages of modernity and its economic appearance, capitalism, the phenomenon of “consumption” did not yet occupy such a central position. For modern industrial products to encompass all areas of life, for technology to replace human labor, a system primarily centered on “production” was initially required. Therefore, all national economies placed great importance on modern factories and production, calling on their citizens at every opportunity to work harder and produce more. This call was so powerful that some, under its influence, believed the essence of capitalism to be the production of industrial goods and structured their analyses accordingly. They failed to foresee that, in time, technological advancements would render much of human labor unnecessary, and that attention would shift to consumption—more and more consumption. For those who still think with the mindset of the previous century and look at matters from that perspective, unable to see that capitalism has evolved into a technomedia form, unfortunately, there is nothing we can do but feel sorry. We are obliged to understand and explain the world we live in well; we have work to do. We will focus on our work.

The phenomenon of consumption is far more complex and difficult to comprehend than production processes. Consumption is an almost endless, perpetual process. Within this process, human beings, generations, worldviews, perceptions of life, and the ideology of everyday life are constantly reshaped over and over again. The consumption process sweeps away traditions, grand narratives, and ideologies—internalizing even them without anyone realizing it.

We must pay very close attention to what we consume, how much we consume, and how we consume. For, beyond many other problems, there is an identity issue that is not immediately visible and is far more important than the others. What we consume, how much we consume, and how we consume are directly related to who we are—our beliefs and our values.

“Consumption” is the hallmark of today’s capitalism and of the society we currently live in. We are immersed in a system that not only wants but demands that we consume more of everything every single day, that we buy the latest model. If we do not resist the pressures of this system, if we cannot save ourselves from being caught between the constantly grinding gears of the consumption machine, then after a while, we may find that we have become unrecognizable. We ourselves—and the values that make us who we are—will have been depleted. If we try to find forced religious justifications (fıkhi cevazlar) for what we do and do nothing beyond that, yes, for a while they may talk about the car we drive, the building we live in, our brand-name clothes and jewelry—but in the end, they will remember our name merely as a simple actor in a consumer society. Our identity as a “member of the consumer society” becomes so dominant that our other identities no longer carry any weight.

Consumption as an Identity Problem in Modern Times

As modernity dismantled traditional structures, the individual—unsure of what to do—embarked on a search for identity through the possibilities offered or imposed by the growing abundance of commodities in the market. An indispensable relationship emerged between life itself, the individual’s state of being, and shopping activities. A person’s body, clothing, manner of speech, use of free time, food and beverage preferences, choice of home and automobile, and sense of taste and style began to be seen as signs of individuality and identity; identity began to be constructed in this way. Consumption became the determinant of identity formation for the individual; it came to shape one’s personal psychology and way of life.

In today’s world, shaped by global consumption patterns, even religious life is affected by this situation—it has begun to merge with other global forms of life, to dissolve in places, and to survive only as a subculture. Despite their structural differences, consumer values and religious values coexist—indeed, are compelled to coexist—within the same society. In such an environment, on one hand, consumption is nearly sanctified; on the other, what is sacred itself becomes an object of consumption. By “the sanctification of consumption,” I mean the attribution of extremely high importance to consumption activities and tools, and the provision of services to people within an almost magical atmosphere. The notion of “the sacred becoming a consumption object” seeks to explain the commodification of elements within the spiritual realm—elements that should remain the same and equally accessible to all.

Capitalism Itself Seems to Be Replacing Religion

We see the phenomenon of the sanctification of consumption most clearly on the special days of the consumer society—what we might call its “ritual days”—such as Black Friday (let us also note in passing the anti-Islamic impulse behind the choice of this name). It takes place on the Friday following Thanksgiving, which is celebrated annually in the United States on the fourth Thursday of November. Black Friday, which emerged as a kind of holiday discount day amid shopping that continues until Christmas celebrations, is rapidly spreading from the U.S. to the entire world. Terms such as “mass hysteria” and “shopping carnival” are used to describe the day, but the most accurate description would be “a consumption ritual.” If consumption has become so indispensable in itself, and shopping has become the most valid path to identity construction and psychological satisfaction, then as one’s attachment to this new belief increases, a person will inevitably become nothing more than a consumer. Capitalism will not hesitate to perform a ritual centered on “discounts” for its congregation of consumers. Both the seller and the buyer will believe they have experienced a cathartic, though false, satisfaction after this ritual and will become even more committed to the belief in consumption. Do not take my use of the word “satisfaction” lightly—for experts are seriously debating whether the pleasure derived from shopping constitutes a form of addiction. One of the Nobel Prizes in Economics was awarded to an economist who studied consumer behavior. The followers of the belief in consumption become so conditioned by this false satisfaction that they can no longer even consider why products are sold at such high prices on days other than this ritual day. Thanks to the satisfaction of Black Friday, society, individuals, and sellers alike indulge in a state of “happy buyer, happy seller.”

At the other end of the sanctification of consumption lies the transformation of the sacred into an object of consumption—that is, the emptying of religious values and symbols of their essence and their reintroduction within the logic of consumption. To witness our desires and wishes—followed by the values that constitute the essence of our identity, our ideals, and the spiritual realm, which is humanity’s most secure refuge—be associated with consumption is painful, deeply distressing… I might say, “Faith tourism is the most innocent of what we are trying to describe, and you can infer the rest,” but you already know it—everything is unfolding right before our eyes.

So then, what must we do, how should we act? This is the hardest question to answer. For we are all children of time—time that flows beyond us, yet also contains us. As human beings, the opportunities afforded to us in every historical era due to our nature as beings endowed with free will still exist today. These opportunities can be summed up as criticism and self-criticism. We must keep the whip of criticism and self-criticism by our side, urging or reining in the horse of time as needed. We must honor our nature as beings of free will, as human beings born into this world—understand the current form of the test we face and act accordingly.