First publication: haber10.com-2014

“A country where thought is free from all fear

a country where people stand tall,

a world not divided by walls,

words springing from the depths of the heart,

labor stretches its arms to the perfection,

the river of reason not dried up in the dark desert of habits,

Oh God, what would happen!

If only my homeland were such a country!”

Tagore

In 1911, the Italians invaded Libya. The Ottoman Empire had made a significant leap with adoption of the the Constitutional Administration Revolution, but Britain, fearing that this constitutional change and its motto “Unity-Freedom-Justice” would set a “bad example” for the peoples of Egypt and India, and Russia, not wanting the Ottomans to regain strength in the Balkans, used every means to suppress this revolution. Inexperienced Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) cadres were being burdened with all kinds of ethnic, religious, economic and political problems. The state was in no condition to confront Italy. The elderly pashas had already written off North Africa with a “Give it up and be safe!” mentality.

In the midst of this atmosphere, a meeting was held at Enver Bey’s house in Beşiktaş, Istanbul. At the end of the meeting, these young cadres, who will lead the Empire’s last line of resistance, agreed on the need to resist Italy. Enver, Talat, Mustafa Kemal, Ali Fuat, Rauf, Ömer Naci, Ömer Fevzi, Kuşçubaşı Eşref… Many more would secretly go to Libya, organize local forces, and start resistance. The plan was conveyed to the Ottoman General Staff, and the young officers were portrayed as deserters, thus ensuring that the official Ottoman stance would not be questioned. Thus, the state would not further provoke the Great Powers but could still secretly support the resistance. Preparations were made, and a handful of young idealists set off for Libya in various disguises and via different routes. Mustafa Kemal, traveling under the fake identity of Mustafa Şerif, a writer for the newspaper Tanin, wrote the following in a letter from Egypt to his childhood friend Salih Bozok:

“Dear brother… As you know, since the Libya matter arose, efforts to go there have not ceased. Once, we were held on a Damascus-bound steamer for three days and then sent back. After that, we tried to go via Tunisia or Egypt…

This time, I left Istanbul with Ömer Naci and two others, aiming to reach our target via Egypt. Even the Minister of War had to farewell us. If necessary and beneficial, I will request some friends. For now, there are points to be secured. Do not reveal where I am. Don’t even inform my mother for some time. Occasionally send letters from Istanbul as if they’re from me…

…How are our friends doing? Now more than ever, effort and sacrifice are essential to save the homeland. Read the last pages of the history of Andalusia… Farewell in God.”

Şerif (Mustafa Kemal), Alexandria – October 4, 1911

The closing lines of the letter properly summarize the reason behind these young officers’ insistence on going to Libya. More precisely, it captures the core of the psychological state the Ottoman Empire entered after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78: “Let our fate not end up like Andalusia!”

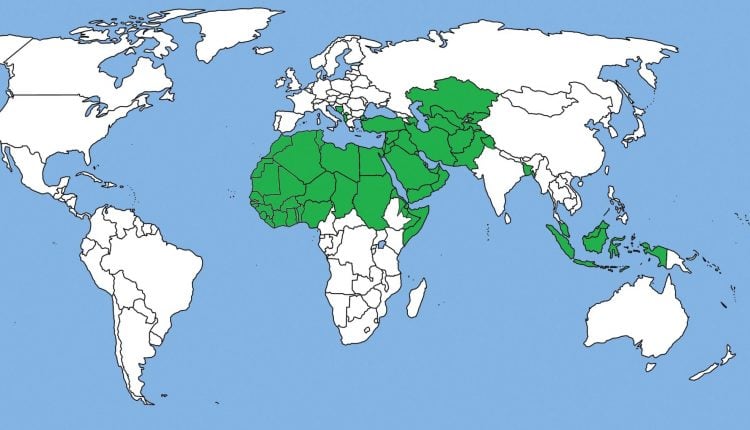

As is known, in Spain, which remained under Islamic rule for 781 years between 711 and 1492, the Muslim population was eliminated as a result of the massacres and exiles by Christians, and by 1614 almost all Muslims had been expelled from Spain. This bloody religious hatred had engraved in all Muslim minds the peak that European barbarism, which had failed to achieve results through invasions such as the Crusades, could reach.

Sultan Abdulhamid and the Unionist cadres who fought against him described this collapse psychology as the fear of becoming like Andalusia, and they tried with all their might to prevent this disaster. This mindset, which viewed the territorial losses in the Balkans as a necessary downsizing to some extent, determined that, as the Armenian incidents escalated and spread to the capital with the raid on the Ottoman Bank, the danger was not defeat and downsizing, but complete annihilation; that is, a danger of the Muslims being expelled from Anatolia forever. After the 93 War, dozens of books were published on Andalusia, and Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah, which described states as organic entities that are born, grow, and die like humans, became widely read. The last intellectual cadres of the Ottomans grew up with this fear and sense of inevitable fate and resisted with all their might to overcome it.

The desire to enter the First World War, the Canal Campaign in Egypt in the middle of the war, and the subsequent relocation policy implemented by Cemal Pasha for Jews, Christians, and Nationalist Arabs in Syria, Lebanon, and Jerusalem were also secret preparations for the understanding that ‘If we are driven out of Anatolia, we will make these regions our homeland.’ Enver Pasha’s decision to abandon his own trip to Berlin with his friends, and instead to launch a new movement first in the Caucasus and then in Turkestan, ultimately stemmed from the same understanding. That is, to prepare a free homeland for Muslims in Turkestan as a last harbourage… Again, the conclusion that the Armenians would be the West’s ally in the region and that the Muslim elements would be expelled piece by piece and cleared from the region would pave the way for a counter-cleansing through relocation of Armenians– and then population exchange.

Fear of Andalusia’s fate permeated the Republic’s fundamental policies. The cadres who sat at the table at Lausanne as Muslim representatives also sought to recognize Kurds as Turks-in the sense of being Muslims-and to reduce the non-Muslim population to a non-threatening level through population exchange. With a perspective in line with the new balance between Britain and Russia, the Kemalist cadres not only eliminated the Unionists and Communists upon Britain’s request, but also tried to prevent possible regional interventions by Russia and France by carrying out the repressions of 1925, 1929 and 1937. Because Bolshevik Russia, under Stalin, had seized Central Asia and the Caucasus and was seeking ways to advance into the Middle East through the Kurds in cooperation with Iran. (Indeed, to realize this dream, the Mahabad Kurdish Republic was established in Iran during World War II with Russian support but was bloodily dismantled shortly thereafter due to the Shah of Iran’s blackmail move toward Britain. Barzani still pursues his father’s dream.)

Meanwhile, France found itself sidelined in the Middle East after World War I, despite having divided the region with Britain under the Sykes-Picot Agreement. The British, through a thousand tricks, had seized Iraq, which had been France’s share, and instead of the oil fields, they had left problematic regions like Syria and Lebanon to the France. As a result, for a long time, France would be behind nearly every development that caused trouble for the Kemalist cadres working in cooperation with Britain. France’s long-standing Armenian policy, the persistent lobbying by Armenians in Syria and Lebanon, and the influence of crypto-Armenians in Anatolia all played a significant role in this French stance. The Kemalist cadres’ harsh reactions and relocation policies, especially towards the Ağrı and Dersim rebellions, were rooted in fears about the fate of Andalusia and concerns that France would establish Armenia and Kurdistan in the region. As World War II approached, the regional balance of power was between France, Russia, Syria and Iran on one side, and Britain, Türkiye, Iraq and Afghanistan on the other. The Turkish response to the Dersim Rebellion that erupted before the war would be the annexation of Hatay. The politics of the involved countries in both events clearly reflect the alignments of these blocs.

Without considering these external factors, one cannot understand the Republic’s apparent anti-religious image on the surface while, in the depths and in the long term, pursuing policies that supported even the strictest interpretations of Sunni Islam in order to cultivate a religious population.

Similarly, the policies of those cadres who knew that there were Kurds in the country to the extent of even discussing autonomy for the Kurds in the early 1920s, and who insisted and stubbornly after 1925 to dissolve Kurdishness into the Turkish identity in the Muslim sense, as the only common legal bond they had imposed at Lausanne, were also a result of similar concerns. The persistent attempt to get the West to accept Kurds as Turks (Muslims) during the Lausanne negotiations was aimed at defining Anatolia as a Muslim country as a whole, thus thwarting any Western demand for an independent state for the Christians remaining in this region and, at the same time, it was aimed at integrating the Kurdish population living in the buffer zone with Iran into the Anatolian union in the long term, taking into account the experience of Iran, Russia, and Britain attempting to exploit certain tribes during World War I. The concern was not about ethnicity, religion, or sect; it was about existence and survival…

That is why the intentions of Republican policies and the methods used to implement them must be evaluated separately. The fear of Andalusia’s fate, when seen through the lens of the period and even a hundred years earlier, represents an understandable survival instinct in the minds of that era’s leaders. But, so to speak, eye surgery was performed with an axe.

The fear of Andalusia’s fate, as a reflex, continued to influence the state’s deep subconscious even after World War II. The Wealth Tax, the September 6–7 September Events, and the open and covert expulsion of the Greek population under the pretext of Cyprus can all be seen as continuations of this policy. It can be said that the same fears continued to govern the state’s reflexes during the concept of the war against Communism before 1980 and during the fight against the PKK after 1980. In fact, the rumor that talked about by the public that the PKK is an organization of Crypto Armenians and that their sole purpose is not Kurdistan but revenge for 1915 – news about uncircumcised terrorists – is not accusatory black propaganda, but rather the occasional expression of an observation. The reasons that give rise to these suspicions are that the PKK began its attacks by raiding Kurdish villages, that it has mercilessly shed the blood of numerous Kurds, including its own members, throughout its history of rebellion, that it has tried to distance the Kurds from the Ottoman and Muslim identity that brought them into history with their own name – or rather, that made the Kurds Kurdish – and that it has tried to take control of the Kurds’ fate by insisting on being the sole authority of appeal on behalf of Kurdishness.

An interesting example reflecting the perspective of ‘Ottoman state intelligence’ regarding Anatolia’s religious, ethnic, and sectarian communities is the work of Baha Said Bey, who was assigned by the Committee of Union and Progress in 1910 to compile an inventory of faith groups in Anatolia. Baha Said Bey continued his field research into Alevism, Bektashism, Nusayrism, and Ahi Communities after the founding of the Republic, and his book: “Türkiye’de Alevi-Bektaşi, Ahi ve Nusayri Zümreleri” contains these revealing lines:

“We have such communities living within the borders of the Republic of Türkiye that Christian groups see no harm in registering them as their converts.

For example, although Kargın, Avşar, Tahtacı, and Çepni Alevis form dense populations, they were generally considered Turkified branches of ‘Orthodox’ Greeks. The Alevis of Dersim, Kiğı, Tercan, Bayburt, and Iğdır also appeared as additions in Armenian census records.

Particularly after the Armistice, Protestant missionary statistics began publishing such data.

Secret Pontic documents kept at the Merzifon American College prove that Christian minorities’ attempts to confuse Europe by portraying these Alevi communities as ‘half-Christian’ and their success in doing so are a cautionary tale that must be examined…” (Baha Said Bey, Türkiye’de Alevi-Bektaşi, Ahi ve Nusayri Zümreleri, Kitabevi Yayınları, Istanbul, 2000)

Another example for understanding the European perspective is the memoirs of Rafael de Nogales Mendez, a devout Catholic from Venezuela who volunteered to fight for Germany in World War I. In his book Four Years Beneath the Crescent (translated into Turkish as Osmanlı Ordusunda Dört Yıl, Yaba Publishing, Istanbul, 2008), Nogales recounts his war memories from the Eastern Front, where he served in an Ottoman uniform with the rank of colonel at the request of the Germans, as well as from the fronts in Mosul, Baghdad, Palestine, and Sinai. He especially took part in battles against Russian and Armenian gangs in the East and witnessed Armenian massacres in places like Van, Bitlis, Muş, and Diyarbakır. In his book, published in English, German, and French after the war, Nogales, blames Armenian leaders for causing the massacres, provides important information for the European public by recording the events he personally participated in and observed. He does not hold the Turks or the Ottoman army responsible for the atrocities but instead blames some commanders, governors, and the Kurdish and Circassian tribes that they mobilized. Arguing that the Armenians had lost their chance to be loyal allies of the West in the region and that they deserved to be destroyed by believing in the Russians and rebelling, Nogales says of the Kurds: “I found the Kurds, or karduchos, to be just as Anabasis describes, except for their weapons… In my opinion, the Kurds are the race of the future in the Near East. They have not been degenerated by the evils of older civilizations. They are a young and courageous nation.” (ibid., p. 51)

These kinds of observations in Nogales’ book, published in 1921, in which he describes to the Western public, as a firsthand witness, which tribes committed the massacres of Christians in which regions, virtually instill the idea that the Kurds could be the new allies of the West in the region, but that they must first suffer the consequences of their crimes.

Contributed to by these and similar ideas, the state reflex has always viewed different identities and demands with suspicion, adopting homogenization or elimination as absolute and expedient solutions.

The fear of Andalusia’s fate also shaped the state’s Islam policy. The closure of religious orders and lodges at the beginning of the Republic was part of the ongoing purge of the Unionists, since many of them had been organized in such institutions. Similarly, after the Sheikh Said Rebellion, there were strong concerns that Iran, Russia, Syria, and France might manipulate the Kurds through religious orders. The Turkish-language call to prayer (ezan) was an experimental application of the European fascist trends of the 1930s. However, mainstream religious orders and communities were always unofficially protected and maintained, controlled and occasionally used as instruments of both domestic and foreign policy.

Again, the post-Cold War anti-communism policy is essentially like a kind of social engineering activity carried out under the guise of anti-communist struggle. Just as the state, fully aware of the existence of the Kurds, refused to recognize any identity other than Turk, it also mobilized large masses under a Sunni-conservative umbrella, despite knowing that there was no real threat of communism, especially not one that would come via a Russian invasion. Because, once again, the issue was not communism but, as always, existence and survival.

The most critical testing ground for the state’s religious policy is not, as is commonly thought, its peculiar secularism (the secularism clause is a formula made up after the Dersim crackdown to keep Alevis loyal to the state and has no other or further meaning or significance) or its policies towards major political-social movements such as the National Salvation Party or the Nurcu movement. These can be interpreted within the context of daily political developments. The real focus should be on the field of education, particularly Qur’an recitation teaching courses.

According to the memoirs of General Ali İhsan Sabis about World War I, a delegate presented a report on religion at the 1916 Congress of the Committee of Union and Progress. Based on a study among Ottoman soldiers, the report noted that many soldiers, those being sent to the front for jihad, could not answer basic religious questions like “Who is your Lord?”, “Who is your Prophet?”, “What is your madhhab?”, “What are the pillars of Islam?”, or “What are the 32 obligations?” and it is explained that the fact that the children of our nation sent to the front lines for jihad did not know their religion, constituted a serious problem, and as a result of discussions on this axis, it was decided to establish an institution that was the predecessor of today’s Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet). The abolishment of the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Foundations (Şer’iye ve Evkaf Vekâleti) after the Republic’s founding, and the establishment of Diyanet, was, like many other ‘reforms,’ actually a continuation of late Ottoman (Second Constitutional) and Unionist programs or decisions. In the early Republican period, religious institutions were officially marginalized, and Diyanet was allowed to operate only in limited ways, to serve the ideological goals of the Republic. However, this situation has led people to find their own solutions, and teaching the Qur’an recitation to the children and providing them with basic religious information in homes, neighborhood mosques, and many other reliable places, has become a major struggle. It was as a result of these efforts that a more widespread and determined effort for religious education than ever before began during the Ottoman period, and almost the entire population, through their own efforts, met their need for basic Islamic education through civilian channels.

The most important feature of this effort is the fact that they ensured the unity and integrity of the Ottoman remnant population not with an artificial and secular Turkish identity invented and imposed by the Republican cadres for the purpose of dissimulation against the West, but with an Ottoman identity identified with Islamic faith, which was the backbone of the Seljuk-Ottoman tradition. In other words, the nation’s survival as a single nation after the great collapse was not achieved thanks to the cosmopolitan-secular official Turkish identity, which actually expressed the Tanzimat-Western lifestyle, as the Republican elites thought, but despite it and by resisting it with defiance and dignity. The only reason why racist or sectarian discord or positivist ideological fanaticism remains marginal in these lands despite everything is that the majority of the nation resists these fake identities with common sense and foresight, and embraces Islam, the true insurance of national identity that has anchored itself in these lands for a thousand years, with the simplest, most basic, but most solid religious and cultural ties. Even all the heretical, marginal, and esoteric currents owe their very safety to this strong cultural foundation upheld by the majority. Because a non-fanatical understanding of Islam inherently includes freedom of thought and tolerance toward different beliefs and practices. The reason why the simple Islamic creed has become the core of the Republic’s fundamental religious policy over time is that the majority of the nation has persistently embraced this path. The essence of this belief is to know the tenets of Islam and faith and to avoid major sins (günah-ı kebair). This belief, which functions as a shared cultural code that manifests itself in the nation’s daily lives, in the fine details of life, and in its perspective on events, has served as a way of perceiving the world and spiritual climate, far beyond being a mere form of belief. In this sense, the collective existence and shared behavioral codes of Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Alevis, Sunnis, Balkan peoples, Caucasians, and others outweigh and transcend their differences, and this is a hopeful dynamic for the future.

This simple indoctrination, which has been passed on to the children, especially through Qur’an recitation teaching courses and similar teaching methods, since the beginning of the Republic, has enabled us to survive as a nation with the same reflexes, the same consistency of thought and perception, from Edirne to Kars, from Diyarbakır to Trabzon, from Antalya to Erzurum. The new identity produced by the official ideology was understood by the majority of the nation as a denial of the historical, social, political and ideal mission of identity based on common cultural codes and as a way to uproot the spirit of the nation and feed it to the West. The real inhabitants of Anatolia were treated as poor and helpless masses who were forced into this fake, later-made costume. The fact that the majority of the nation still lives in the same neighborhoods and buildings, and takes sides in the same mosque, despite this multifaceted oppression, is due to the fact that this fundamental belief has been persistently and dauntlessly passed on to the new generations in tens of thousands of mosques, Qur’an recitation courses, and homes across the country for a century. The Islamic creed is the sole foundation for making this land a homeland, for the state’s survival, and for the nation’s acquisition of a shared memory, ideal, and identity. If lasting peace, social tranquility, and security are to be ensured in these lands, if the lifestyles of all sects and ideological groups are to be secured, and if the state is to assume the role of arbiter of these shared sensitivities, the way to achieve this is to deepen and continue this dynamic of existence and survival, determined by the faith of the majority of the nation. The conservative-religious side of the nation has continued to exist precisely for the purpose of continuing this effort.

Ultimately, while the state, as the official established order, tried to solve its existence and survival problem with totalitarian and authoritarian policies resulting from the fear of Andalusia’s fate, the nation solved this problem de facto, and in most cases, despite the state, by holding on firmly to the Ottoman-Islamic identity and values.

Despite all opposing efforts, the majority of society has not had a problem with these values. The glue that holds together Alevis and Sunnis, Turkmens and Kurds, Bosniaks and Arabs, Circassians and Albanians is nothing other than these values. Ethnic or sectarian-based differences or demands only emerge when these shared values are neglected, abandoned, or eroded. This understanding, which sees every human being as a venerable, every difference as a sign from God, perceives everyone as a brother in Adam (pbuh), a companion in Abraham (pbuh), Moses (pbuh), and Jesus (pbuh), and a co-religionist in Muhammad (pbuh), sees taking responsibility for their words, actions, and morals as the essence of morality, considers treating the oppressor as oppressor and the oppressed as oppressed as jihad, caring for the orphan and the poor as worship, and not being a servant to someone else as a matter of dignity, considers all forms of discrimination to be discord, all forms of oppression and terrorism to be corruption, and regards the state as justice, the nation as solidarity, and the homeland as honor, is a mutual insurance so sensitive that, if abandoned, it will lead to deterioration, decay, contradiction, and conflict. Therefore, the construction of the social future is possible when Turks, Kurds, Alevis, Sunnis, etc. gather around this common understanding and unite around the goal of making this understanding the basis of the social contract, the constitution, and the state.

Fears of Andalusia’s fate should be removed from the agenda not because the reasons and conditions that gave rise to them have disappeared, but because they must be confronted and overcome. At this point, Türkiye cannot determine its future based on its fears. Yes, the trauma of World War I appears to have been managed throughout the 20th century with security policies rooted in these fears. But the idea of creating a new nation, and the method of implementing it through oppression and purge, has not only led to new problems but also left Türkiye facing new challenges with both material and moral costs. Now, taking this experience into account, it is more reasonable and constructive to look again at the spiritual roots of the nation and to re-discover the simple, modest, yet solid values found there, transforming them into components of a shared identity. In other words, whatever the purpose of the effort to create a new nation and sustain it within the nation-state form, it should be put forward as everyone’s responsibility to focus on that purpose and, in particular, to focus on re-enforcement of the unity and order of the state and the nation by modifying the methods. It should now be understood that presenting decisions regarding Türkiye’s existence and perpetuity as if they were orders and indisputable laws given from above is disturbing and actually produces counterproductive results. To move forward, we must first stop treating certain concepts and phenomena as divine commandments or sacred untouchables that cannot be questioned, debated, or changed. Neither independence, nor the integrity of the state and nation, nor a free and common future can be discussed with the stately language that sees society as a child and constantly speaks with reprimands. The growth of this country is possible only if it first grows at the socio-psychological level, that is, becomes an adolescent. An adolescent social consciousness means a society composed of individuals with a sense of belonging and dignity who take control of their own destiny. The era of ruling a country through commands and prohibitions, scolding and praise, punishment and reward has come to an end. It is necessary to use all social tools as incentives to make each and every one of our people, and especially our children, outstanding individuals who can speak more, discuss, object, decide, choose, reject, trust themselves, their nation, and their country, that is, who have a sense of responsibility. A secure and hopeful future for all can only be built if all of us feel secure and hopeful. The ideology, philosophy, path, and methods of achieving this should be seen as adjustable details that can be determined through democratic processes. When there is no social trust, every idea or methodological step disturbs someone else, turns into a major social problem, and produces anxiety and concerns. Therefore, we must all commit to embracing freedom, justice, fairness, and compassion as shared values.

Today, Türkiye stands at a critical threshold. At this juncture, we may witness a process that could be described as re-nation-building. But this will be possible not through identity displays imposed from above or strange imitations of multiple identities injected from outside, but through a return to what is real, what is normal, what is natural. What Türkiye needs more than anything today is normalization. The state must act like a proper state, the judiciary like a true judiciary, politics like genuine politics, and the economy like a real economy. All the topics of discussion such as Turkishness, Kurdishness, Alevism, secularism etc. should be able to be discussed to the end and displayed in all their naturalness. Everyone must believe that bans divide, but freedoms unite. No one can act as the owner, master, or decision-making authority of this state, this homeland, this country, but the common decision-making authority on which everyone will agree is the willpower of the majority of the nation, until something better and more just is proposed. The nation itself is the referee, the judge, the subject, and the master. To this end, an organic and healthy environment for democratization must be created that will include all elements, voices, and colors of the nation in the process and neutralize any tutelary intervention through the nation’s reaction. Politics must create an environment in which even the most ordinary citizen, including the elite of the state, can speak without fear or accusation. In this context, normalization will be achieved through deepened democratic mechanisms and active participation. In other words, tautological discussions between the parties to the problems or the position where one side demands something from the other and the other makes decisions in an imperious and selective manner should be abandoned, and a dynamic environment of conversation and dialogue should be created in which free and equal citizens discuss their common future. Of course, there will be those who seek to exploit such a space. But in such an environment, all elements and discourses that are one-sided, narrow, fruitless, excluding, divisive, or that incite hatred and hostility will be eliminated by the nation and will be marginalized naturally.

Just as the regime, Turkishness, secularism, or the republic has no sole owner, neither does religion, Kurdishness, Alevism, or democracy. The only true owner is the nation itself. Ownership lies solely in greater freedom, and the most reasonable balance can only be achieved through democratic means. In this context, the more elements, groups, communities, beliefs, organizations, and most importantly, individuals who volunteer to participate in the process, the more effective the results will be. The sole role of the state, with all its institutions and organizations, in such a process is to provide objective oversight and ensure the security of the environment. Moreover, such an environment will also enable the opening, relaxation and normalization of closed circles based on ethnic, religious or sectarian principles that try to exist by deriving counter-fears from the fears that are the deep reflexes of the state. Indeed, in the last ten years, when it was possible to speak without fear, many issues that had previously caused suffering to hundreds of thousands of people through legal and illegal oppression were freely voiced and expressed openly, but there was no development that would confirm the oppressive policies that statesmen pursued in those previous years out of fear of losing secularism, Turkishness, the republic, and the homeland. On the contrary, the true existence of many groups, organizations and communities that have gained strength from their oppositional and oppressed positions and have become imitations of the state apparatus, reproduced in reverse, with their closed and introverted structures, has been revealed and has become debatable. It is a virtue to resist oppression, but protecting people from the refined forms of pressure that resisters themselves may create over time must also be considered a virtue. Even this situation has been an important experience for us to understand that more freedom is not a blessing or a choice, but a necessary order-building medium.

Türkiye is progressing by changing and transforming altogether. Where this process will lead will be determined by a march in which everyone participates together. Naturally, different solutions and shared goals and ideals will be proposed to society, and society will make its choice among them. But the important thing is to ensure everyone’s participation in this transformation, to complete this path without excluding anyone and without allowing anyone to exclude anyone else. Therefore, it is important to try to include differences or different voices in the process rather than trying to eliminate them, no matter how contradictory they may seem. Even the most marginal or extreme idea – unless it is aimed at discord and provocation, which is something that can be eliminated by society – should be able to express itself freely so that the average of society can emerge.

Normalization, participation, and collective transformation… Türkiye’s ability to overcome its 20th-century fears, experience healthy change, and activate lasting development dynamics lies in these three concepts. We can answer the questions of how we might achieve this, in what context we can discuss it, and on what foundations we can build the future by looking at our historical experience. In this context, the Seljuk experience, more than the Ottoman one, can open new horizons for us…

First publication: haber10.com – 2014