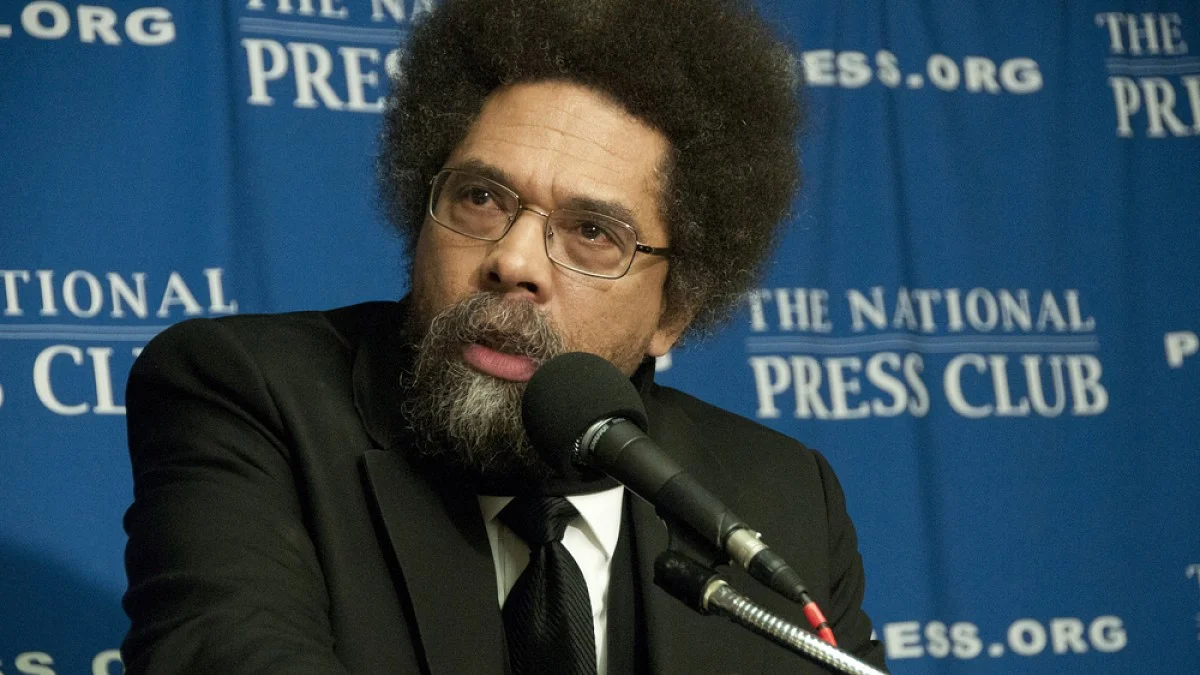

Dr. Cornel West is a scholar, an activist, and the author and editor of more than 20 books, including Race Matters and The Radical King. He was also a candidate for president in the 2024 election, where he ran on an anti-war platform. He recently joined Current Affairs to discuss the crisis of the U.S. empire, the nihilism of Donald Trump and the Democratic Party establishment, and how we can find hope and solidarity in dark times.

NATHAN J. ROBINSON

Dr. West, thank you so much for joining us on Current Affairs today.

CORNEL WEST

Well, my brother, I want to thank you. And first, I just want to salute you for being such a force for good. Congratulations on your 50th issue. It’s been magnificent. And of course, that powerful book that you and Noam Chomsky wrote, The Myth of American Idealism. It begins looking for a place in the parking lot and ends up with the great A.J. Muste, who has been overlooked.

ROBİNSON

Indeed. Thank you very much for that kindness, Dr. West. I wanted to talk to you in particular, though, because Professor Chomsky is someone whose voice is so necessary and powerful in dark times, and you are another person who I turn to for solace and encouragement in dark and bleak times. And that is what I think we are very much in. One of the reasons I want to talk to you is because you were one of the few people in American public life who talks honestly and unashamedly about love. There was a recent quote from—you probably saw—Vice President J.D. Vance where he was talking about, essentially, why we didn’t really need to care that much about immigrants. He said there’s a Christian concept of the Ordo Amoris—this is the hierarchy of the people you’re supposed to love. And he said our first obligation is to love our family, then our fellow citizens, and then we can care about the rest of the world later. Essentially, we don’t have to love the rest of the world. And as I heard that, you were actually the person I thought of because you have been such an advocate for and a spokesperson for the deepest concept of Christian love, of brotherhood, of humanity. And I wonder if you could tell me your reaction when you hear that kind of Christian justification for, essentially, cruelty.

WEST

Well, absolutely, it’s the worst kind of rationalization of indifference. And the great rabbi Joshua Heschel used to say, indifference is the very essence of what sin is—a cold heart, a coarse unconscious, and a callousness toward the suffering of others, especially the most vulnerable: the orphans, the widows, the motherless, the fatherless, the oppressed, the subjugated, the demeaned, the degraded. There was a philosophical doctrine called “self-referential altruism” that was put forward about 45 years ago and the philosophers went at it tooth and nail because, of course, given the kind of narcissism, not just in Vance, but in all of us, we have to kill it every day.

The great Goethe says you’ve got to wake up and kill the worst inside of you in order to win what he called freedom and existence, and he’s right about that. Of course, Christians talk about learning how to die every day. When Dorothy Day wrote her eulogy for Martin Luther King Jr., she said he learned how to die every day. What does that mean? That means dealing with the hatred and the envy and the greed and the resentment inside of each and every one of us to emerge with courage. And one of the distinctive features of the decline of the American empire—and it’s a sad thing because we’re watching it in real time: the decay, the decline, the dissolution—is the spiritual and the moral cowardliness—the civic cowardliness. And so we can talk about a huge military and about how your economy is doing, but if your political system is not predicated on a civic virtue and courage to reach out and be concerned about others, then the political system is a house of cards. James Madison understood that you can’t proceed without civic virtue. We know that John Adams said the same thing. These are not the most revolutionary thinkers around, but they got some insights, though, brother.

ROBİNSON

When you talk about waking up every day and killing the worst that’s inside you, it strikes me that Donald Trump is someone who essentially flips that doctrine on its head, and wakes up every day and celebrates the worst that is inside him and says, no, you should embrace it. You should lean into it. You should act upon all of your worst impulses, and you should do so unashamedly. You should never apologize. In fact, Vance reacted very negatively when someone suggested that this racist employee at the Department of Government Efficiency should be rehired. And they said, shouldn’t he apologize first? And Vance suggested that even to apologize for a racist statement was a form of what he called emotional blackmail. The White House posted for Valentine’s Day a message, “Roses are red, violets are blue, if you’re here illegally, will deport you,” and they posted a video of someone being shackled for a deportation flight. It really does seem that this doctrine of taking these worst impulses and destroying them, you could really go in the exact opposite direction, and now that is what seems to be in power in this country.

WEST

I think you’re absolutely right, brother. You might recall one of your epigraphs is from Thucydides, and Thucydides was a favorite writer of Nietzsche, and both of them put a premium on the centrality of war and strength and the relative feebleness of trying to create interruptions in the history of the species dominated by war, dominated by oppression, dominated by exploitation. And it’s a very important juxtaposition to see somebody like Trump. You’d have to get partly into his own formation and so on. He had a very precious mother from Scotland who made it here penniless, Mary Anne. And she used to tell [Donald] Trump, I just hope you don’t grow up to be somebody that I’m ashamed of. I just hope you grow up to be somebody I can be proud of, not based on the money you have, but based on who you are. Now, she’s coming out of a working-class situation, in a highly impoverished situation in Scotland. As an immigrant, she comes to the United States and meets Fred, Trump’s father. But Trump has this element in his past that he continually pushes aside because Roy Cohn and a whole host of others, including his father, had socialized him into a “might makes right” view of the world. The Ten Commandments mean nothing. The eleventh commandment, “Thou shalt not get caught,” is the only important one.

ROBİNSON

Yes, right.

WEST

Life is a matter of a survival of the slickest and the richest and the smartest. Now, he’s not all alone. America in general, and not just America—empires in general. There’s been 70 empires in the history of the species. The United States is the 68th empire in the history of species. You know that, but the United States is unique because it denies it’s an empire. And therefore you can’t understand the truth. That’s what to me what American idealism is.

ROBİNSON

That’s right.

WEST

And how U.S. foreign policy endangers the world. You deny you’re an empire. You deny the power that you exert and the violence that you promote, in the name of what? Innocence. James Baldwin said what? That innocence itself is a crime. And so Trump is a manifestation of the worst of the U.S. Empire. But he’s had elements inside of him that he had thoroughly ignored, and he ends up choosing to be a gangster. Now, a gangster is different than a hypocrite. Hypocrisy is the tribute that vice plays to virtue. Hypocrites have standards, they just violate them. Gangsters have no standards. They say anything, do anything, and think they can get away with it. No accountability, no answerability, no responsibility. That’s the history of Trump.

That’s also the history of the U.S. Empire, in terms of its attempt to shape the world in its own image and interest. So then here comes those prophetic ones. I was so glad you invoked Melville, brother. Because what does Melville say in Moby Dick? America, you are addicted to self-destruction, and if you don’t learn how to muster the courage to think critically and to love and be concerned about the least of these, just like the Pequod, the ship of that powerful epic he wrote at 32 years old, you’re going under. And how does it end? Ishmael is on top of what? A coffin. The ship goes under. That self-destruction overwhelms the moral and spiritual forces. But those of us who are committed to the moral and spiritual forces will hold on. See, I come from a people, brother, who’ve been on intimate relations with catastrophe, calamity, monstrosity—244 years of the most barbaric slavery of modern times, and then another hundred years of neo-slavery, of Jim and Jane Crow, lynching black folk every two and a half days for 50 years. How do we generate some courage to love, courage to hope, courage to resist, courage to remember, courage to have a reference for something bigger than our egos? Moral and spiritual cultivation. How do you cultivate? By example, not by textbook. No, not by words on paper. There are beautiful words on paper in the US Constitution. It was pro-slavery in practice. We’re talking about actual examples—practices. That’s the key thing, though, brother.

ROBİNSON

Yes, one of the things I appreciate about you, and I think that everyone who meets you and interacts with you notices, is that you do put a lot of effort into, on an interpersonal level, spreading joy. In your daily practice—your famous calling of people, brothers and sisters. There’s a political purpose to that. It’s not just a little Cornel West eccentricity. It is something that you do that, on a small level, makes people feel something.

WEST

I think a lot of it has to do with just being the son of Clifton and Irene West, and spending my [childhood at] Shiloh Baptist Church. A certain deep Christian formation and cultivation, there’s no doubt about that. Like when I encountered the sick white brothers down in Charlottesville, and they came up to me and said, I can’t stand the fact you call everybody brother. I can’t stand that. And I said, Oh, really, brother. And he said, Oh, you called me brother too. I said, That’s right. I think God loves you just like God loves me, but I’m a free Black man, and I do not ask for your permission as to who I love, how I laugh, or how I struggle or how I resist. There’s a freedom in that love, but it’s a matter of trying to stay in contact with the humanity of others. The Klan and neo-Nazis and so forth choose to be thorough-going gangsters. There’s no doubt about that, but I also acknowledge I’ve got gangster proclivities in me. I have to fight it every day, and they’re still my foes. They’re still my enemy. But there are ways of staying in contact with the humanity of even your enemy.

ROBİNSON

Well, this is what I would love for you to expand upon a little bit. I think that many people who have Trump-supporting relatives struggle with the question of, how do you love someone who is supportive of something you find repellent and cruel and monstrous? How do you engage with—should you engage with—people you know who are far on the right? Should you sit down with them? To what degree should you collaborate with them? Should you shun them entirely? You think a lot about this. You sit down with people. I saw you have a long conversation with Candace Owens, someone who I think many on the left would find completely repellent. But you sat down, and you had a cordial conversation. At the same time, you always know your enemy. You always know what you’re fighting, and you still talk in the language of having an enemy and knowing that there are forces of evil in the world. You are not someone who says, well, we need to put aside all of our differences. Barack Obama famously said, there’s no red America or blue America, there’s just the United States of America, and we just need to set aside our differences and all get along. But that’s not what you’re doing.

WEST

Oh, that’s right. You’re absolutely right about that, brother. Absolutely. You probably know the new book that I’ve been blessed to put out with my dear brother Robbie George called Truth Matters: A Dialogue on Fruitful Disagreement in an Age of Division, that just dropped a couple of weeks ago, and we got a chance to lay this out. He’s a conservative Republican brother, I am who I am, and we’re able to revel in each other’s humanity even as we have these disagreements. But part of it has to do with the fact that you recognize that everyone is going through a process, and everyone can change. They can change from better to worse. They can change from worse to better. And so you never foreclose anybody’s possibility of undergoing change. That’s one thing. All of us are in process. On the other hand, we’re not naive, not at all. I love how you call brother Chomsky a sincere idealist.

ROBİNSON

You’re right.

WEST

I love that. I love the wonderful book by William Andrew Swanberg called The Last Idealist. He’s talking about Norman Thomas, who was a great socialist leader, and a good friend of Muste in that regard. Well, what was it about them? They had a humility. They knew, in fact, that they could be wrong, but they were convinced that they could be enforcers for good, and therefore they were always open to people undergoing change. And that’s very important. A number of our comrades started off in a very different place. A number of folk who used to be with us got cowardly. They sold out. Went centrist. Some of them went further to the right, not for an intellectual reason, but just for money. Well, we know human beings are human beings, but we’re all, in the end, brother, made in the image of a loving and mighty God that has a dignity and a sanctity. Now, if you don’t believe in God, you can just say, well, human beings have a dignity and a sanctity that’s never reducible just to their politics.

ROBİNSON

You must have encountered criticism from people on the left for collaborating with someone like Robert George, who is staunchly anti-abortion, for instance, who is a strong conservative Christian. Or, I think when Ron DeSantis was proposing getting the classics back into education, and you said, well, that part of his agenda is good, and many leftists said, Cornel West is praising Ron DeSantis—don’t you understand you are naive about the right-wing political project? I’ve said that you’re not naive about it. So how do you respond when people say things like, what are you doing praising something Ron DeSantis is doing? What are you doing collaborating with someone like Robert George, who celebrates the taking away of a woman’s right to choose?

WEST

Well, I just tell them that I have deep opposition to my dear brother Robert’s position, and we fight it out. But we also overlap on other things, in terms of we both have concern about anti-poverty programs. So, we’re concerned about children once they’ve arrived. So many folk who talk about abortion don’t say a mumbling word about the levels of child poverty. Child poverty is one of the crimes against humanity in America, among a whole host of others—mass incarceration and others. We can go on and on and on. But I wouldn’t call it a collaboration, though, brother, I would call it more a Socratic conversation that tries to see where we overlap. Now, your sister Lily Sánchez, who wrote that inspiring piece—

ROBİNSON

About your presidential campaign.

WEST

Exactly. She laid this out very well. She said, look, brother West is a free man, and he chooses various issues that mean much to him. And if somebody says Shakespeare or Dante or Melville and so forth are to be marginalized, I say, no—that’s like marginalizing Coltrane, Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, and Sarah Vaughan. We’re talking about levels of excellence that must never, ever be degraded. And it comes in a number of different forms. We could talk about it with [Rabindranath] Tagore in India. We could talk about it in terms of [Chinua] Achebe in Africa. There are certain forms of excellence that we must always affirm, no matter where it comes from. It can come from Europe, Africa, Asia, and what have you. And if, in fact, it looks like the right-wing talking about excellence in Europe, I’m not right-wing if I talk about my love for Chekhov and Melville and Shakespeare at all. I’m a free man. I’m speaking my mind. I’m being honest. I’m being candid.

ROBİNSON

Well, one of the things people may notice when they hear you talk or read your writing, is that you do drop references from so many varied sources, from music, from literature, from philosophy. And it strikes me, as I was going back through your writing, that so much of your kind of broad intellectual project has been an attempt to fuse various things that people don’t always see as being part of one thing, and to draw out these rich spiritual traditions, musical traditions, philosophical traditions, literary traditions, and to show human beings what we have produced, and to encourage us and to see it as all part of something that everyone’s entitled to enjoy. Everyone’s entitled to enjoy the blues, and everyone’s entitled to enjoy Shakespeare. Tell us a little bit more about this effort, because I do think this is something that’s true of your writing that isn’t true of most people. Most people are not going to read William James and John Coltrane and Shakespeare in the same paragraph.

WEST

You are very kind, brother. I was just blessed to give the Gifford Lectures there in Scotland, which is the magnificent series of lectures people have given, from William James, John Dewey, Alfred North Whitehead to Reinhold Niebuhr, Paul Tillich, and others. And it was on “A Jazz-soaked Philosophy for our Catastrophic Times: From Socrates to Coltrane.” And those six lectures try to do exactly what you just talked about, but it has to do with just me trying to be true to myself, because I am who I am and because people have poured so much into me. I got the Shiloh Baptist Church. I got the Black Panther Party. I got Harvard College with John Rawls and Robert Nozick and Judith Shklar, who talked about the centrality of cruelty. I’ve got Princeton with Richard Rorty and—

ROBİNSON

And Marxism, of course, was an influence on you.

WEST

The Black Panther Party introduced me to Marxism and study of Fanon and others. That’s been an integral part. But it’s just a matter of trying to get at the truth. See, that’s the fundamental thing. Is it true that capitalism is a system with asymmetric relations of power at the workplace, where greedy bosses can get away with no accountability as workers barely make it from week to week? Absolutely right. It’s not an “ism” at all. We know about the truth. You don’t have to be a Marxist to accept that. And so it is.

But anarchism is the same way—the anarchist suspicion of the nation-state and its monopoly on instrumentalities of violence, and that nation-state, whoever tends to head it, becomes corrupt. And no doubt, power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Chomsky is right. Kropotkin is right. Proudhon is right. So it’s just a matter of the truth, and I’m just being true to myself, saying what? All these things have shaped who I am. From the street to Marvin Gaye to Curtis Mayfield to Plato[…], these are people who mean much to me in terms of who I am, and I would be untrue to myself if I acted as if they don’t mean anything to me. And one has to be true to whatever self that we’ve been able to shape over time, because there’s no self that’s isolated. Every self has been shaped by other selves. And I’m sure you were viewed in the same way, in terms of who you are and all the voices that have been inside of you that shaped you in such a way that you have been able to find your distinctive voice of Current Affairs and be such a force for good.

ROBİNSON

I was going back to Race Matters from 1993, so over 30 years ago now. The book kind of made you a public name in America. Up until then, you’d been doing a lot of academic writing and were widely respected as a philosopher, but this was a public-facing book. And to read this and reflect on where we actually went in the last 30 years, you said:

In these downbeat times, we need as much hope and courage as we do vision and analysis. We must accept the best of each other, even as we point out the vicious effects of our racial divide and the pernicious consequences of our maldistribution of wealth and power. We simply cannot enter the 21st century at each other’s throats, even as we acknowledge the weighty forces of racism, patriarchy, economic inequality, homophobia and ecological abuse [at our necks].

I feel like we did not heed that prophetic warning, and we did, in fact, enter the 21st century rather at each other’s throats, at least in the United States of America.

WEST

No, I think you’re right about that, brother. You’re absolutely right about that. And in that next text, Democracy Matters, I put at the very center of it nihilism: the nihilism of the ruling classes, of the professional elite, of the professional managerial strata, and how that was connected to the nihilism I was talking about in the hoods, in black communities. Nihilism is probably the major movement on the globe, and it goes hand in hand with fascism. Nihilism is a view that might makes right, that there’s no possibility of hope as it relates to poor people, as it relates to human beings relating to each other as human beings. All life is domination, manipulation, transaction, and everything is subject to being not just sold, but for being used and abused. So it’s just as bleak a nightmare as you can get. We see it in Hungary—we see it around the world, but it’s triumphant now. Martin Luther King Jr. said at the Nobel Prize in 1964, “Right, [temporarily] defeated, is more powerful than evil triumphant.” Martin, where did that come from, brother? That naive idealism—or is it? No. He said, I’m describing a love and a courage and a joy in me that the world can never take away, that the world can never crush.

ROBİNSON

You are the editor of a volume of Martin Luther King Jr.’s writings, The Radical King. Nobody is more abused in terms of their reputation in the 21st century, perhaps, than Martin Luther King Jr. Nobody is more misrepresented or misunderstood. The right has certainly tried to appropriate King, their own version of King—the King they could use to bash DEI and say, but don’t judge people on the color of their skin. That’s all they want to know. And one of the things you’ve tried to do is explain that Martin Luther King Jr., in fact, had a deep, comprehensive, and broad vision of social justice. It was a democratic socialist vision, and it is one that we can return to in bleak times.

WEST

Martin Luther King, Jr. received a call that he had been chosen to receive the Nobel Prize, and he said, no, give it to Norman Thomas, because he was a member of the Socialist Intercollegiate Organization at BU as a Christian socialist. Norman Thomas meant the world to him. He wrote an essay called “The Bravest Man I Ever Met” about Norman Thomas. So, yes, you’re right about the democratic socialist element, but socialism was not the crucial thing for Martin. It was, how do you create a public life in such a way that citizens are able to live lives of decency and dignity, and have some mechanisms of accountability for the asymmetric relation of power of greedy bosses and workers wrestling with wage stagnation? That was his question.

That question is still crucial these days. The neoliberals couldn’t answer it because they allowed for the inequality to flourish. And here come the neofascists, who do what? Tell working people and poor people to scapegoat the most vulnerable rather than confront the most powerful. That any moral substance, any spiritual content of your politics ought to be pushed aside. It’s all about power. It’s all about manipulation. It’s all about who wins, who has the most money, who has the most access to resources. No, Martin says, I believe that, in fact, looking at the world through a moral and spiritual lens is the only way, even though it seemed weak and feeble because it only creates these moments of interruption, given the dominant tendencies of the species, which has, in fact, been those of organized greed and weaponized hatred and institutionalized indifference to the vulnerable. That’s the history of the species. There’s no doubt about that. When Hegel said, “history as a slaughter-bench,” he’s right about that.

ROBİNSON

Well, to avoid giving people the wrong impression about where you stand, based on what we’ve said so far, we talked about neofascism and about Trump as the kind of embodiment of this “might makes right” ideology, this nihilistic idea that there are no values that you need to respect except getting what you can and keeping it—following, as you said, the 11th commandment. However, people might say, that’s why people should have voted for Kamala Harris, but of course, you have been a staunch critic of the Democratic Party as being inadequate, hypocritical, and failing to understand and acknowledge these deep injustices. Of course, you ran a third party presidential campaign, and people said to you many times, but you’re going to get the greater evil into power. We need to all rally behind the lesser evil. You rejected that logic, and so you must see there being a very deep problem with the so-called opposition. So perhaps you could elaborate on that for us.

WEST

Yes, I think part of the sadness, my brother, is that once the Democratic Party unjustly and unfairly made it impossible for brother Bernie to gain access to leadership, it was clear to me that the party was beyond redemption. It meant that the party was so beholden to its benefactors, its donors, the corporate elite, that the progressives in the Democratic Party would be marginal and on the fringe, just like Bernie and the Squad and so forth, but we’ll never be able to really have leadership over the Democratic Party. I said we’ve got to look somewhere else. Continually finding ourselves supporting, let’s say, a Kamala Harris, means genocide, which is the crime against crime against crimes of humanity.

You can’t say a word about poverty [as a Democrat]. It’s only the middle class you talk about. You can’t say a word about mass incarceration, which still plays such an ugly role in the shaping of poor people, just supposedly black and brown. You can’t say a mumbling word, a substantive word, about ecological crisis. So that I’ve said to myself, if this is all the U.S. Empire can present when it’s in the middle of its crisis, that it denies, it’s neofascism and neoliberalism, then we’ve got to look another way. We have no other alternative. If you’re concerned about truth, justice, and love, we’ve got to look another way. And what did those in American history do in the 19th century, when they had to choose between two slaveholders? They formed another party, and it looked as if they were not just on the fringe, but the kind of lunatic fringe, these abolitionists and so forth. Well, not really. They had to tell the truth about the evil in the society.

ROBİNSON

You’ve been a staunch critic for a long time of America’s elite institutions, even its liberal institutions. You have famously taught at all the top Ivy League universities. But you’ve also been critical. In 2021, when you left Harvard, you pointed out that their commitment to their professed values of “veritas” were shaky, to understate it. You’ve also pointed out the kind of the hypocrisy on Palestine. Being someone who has seen more of the inside of these institutions than most people will ever get to see, I wonder if you could elaborate a little bit. Again, most of these institutions—top universities—consider themselves the liberal defenders of culture and decency and democracy, against an uncultured boor like Donald Trump who is destroying our democracy. You say, well, hang on a minute, Harvard University is not exactly pure itself.

WEST

Oh, no, absolutely. Absolutely. Part of it, my brother, is that all the institutions in the American empire become so commodified, and higher education became commodified and corporatized. So it became very difficult for faculties to wield their power in the name of the life of the mind. It became a matter of money, money, money, position, position, position, status, status, status. That’s how you ended up producing the meritocracy. The students themselves come in looking for a career and profession, rather than critical engagement and what it means to be a force for good as a citizen. And so, once the market takes over, you end up with the life of the mind being tertiary. When Larry Summers and I had our big fight back in 2001, it had nothing to do with the life of the mind. He was talking about, West hasn’t published—I published 13 books. Quit lying, brother. Trump’s not the only one who lies. Then we had another fight again 18 years later. It had nothing to do with the life of the mind. It had to do with the fact that I was a faculty advisor for the Students for Justice for Palestine, and also faculty advisor for the gospel choir at the same time. They were not going to allow this kind of so-called pro-Palestinian presence on the faculty that has this kind of visibility. And it was very clear to anybody who could see that.

ROBİNSON

I did my PhD at Harvard as well. And one of the things that was kind of striking to me was the idea that being political necessarily meant that your scholarship was weak, and to speak to a broad audience also meant that your scholarship was weak. I once wrote a paper about landlord-tenant court in Boston, and my advisor said, it seems like you’re on the side of the tenants, and that means that this paper is weak because you’re clearly biased. And I said, well, no, everything I’ve said is true. And the criticisms that were launched at you were kind of interesting, the idea that the more you engage with the public and speak on things that really deeply matter in a moral sense diminishes instead of improves your standard as a scholar—that it makes you frivolous or trivial or somehow reduces the quality of your thought.

WEST

Well, but the thing is, though, brother, when you get figures like Samuel Huntington, Daniel Moynihan, or Henry Kissinger, these are public intellectuals.

ROBİNSON

Oh sure, those guys get to do it.

WEST

Yes, exactly. The stature and the culture—people that defer to them are justifying the power of wealth, justifying hierarchies that are illegitimate, and we can go on and on and on. So it really depends on which dance—if I came out for the property owners, it would have been very different. Absolutely. But I want to just speak directly to you, brother, because I think you play a very important role in the culture. Do not get discouraged. Be encouraged and of great courage. Your voice matters. Your witness matters. And as a young, serious intellectual, engaging the life of the mind, finding joy in the life of the mind, not just in the instrumental way and using ideas for politics—there’s a joy in the life of the mind. Never apologize for that. That’s like John Coltrane apologizing because he’s playing the saxophone, a European instrument. He loves playing that instrument, but in that love of playing that instrument, he also knows he can inspire and illuminate and instruct people to be more courageous forces for good, in solidarity with the poor around the world, in every culture and every continent. And so we’re in a very dim and grim time, but we have to have a blues sensibility. And the blues is about wrestling with catastrophe, but never allowing catastrophe to have the last word, because we have a love and a courage and a joy inside of us that can never be taken away.

They can try to take us to jail because we need to engage in some serious resistance. I loved your piece on resistance, though, brother. We’re having a wonderful meeting tonight here in Harlem at the Revolution Books with brother Carl Dix and others on this. And I was just with Reggie Workman last night, who played bass for John Coltrane. He’s 87 years old, and he said, brother West, how can I be of resistance? He’s a great jazz pianist. That’s the folk we have to be part and parcel of, because as things get worse, the powers that be are trying to break our spirits. And our spirits should never, ever be broken. That’s what love is. It could never be crushed, brother. Never.

ROBİNSON

You speak to me, and obviously, I need to hear this a lot myself. But our readers, importantly, write in and say, I really do feel it’s not like it was in 2017 where there are vast street protests, that this seems to be a lot of Trump fatigue with a lot of people wanting to sort of lay down and just let the steamroller roll over them. And it is our job as a left magazine to rally the troops, to exhort them. And again, one of the great things about your work, and the reasons that I encourage people to read it, is because, as you’ve hinted, you are deeply engaged with history and the history of social struggles. You can look over hundreds of years, and you can look at all these people who struggled in far more dire circumstances than we even do today—people who faced an even greater risk of death in the age of lynching, in the age of slavery, and who were able to persist and resist nonetheless. And so, the study of history can really actually bring quite a lot of consolation and encouragement to us at the moment.

WEST

That’s very true. But at the same time, Keats talked about the negative capability being in the midst of mystery and uncertainty without any irritable reaching after fact or reason. What he meant by that was there are no guarantees, ever. There are no guarantees that will win. There are no guarantees that there’s victory. But this is the kind of human being, this is the kind of movement, you choose to be in and be a part of, and that is what it is to bear witness. That’s what it is to have a calling. That’s what it is to have a vocation rooted in a tradition of remembrance and reverence and resistance. And T.S. Eliot says, “Ours is in the trying. The rest is not our business.”

We’re not in control of history. We’ve got a life to live, and if that life leads us to hit the street and go to jail and get killed, that’s the life we live. And we’re going to put a smile on grandma’s face, because she wanted us to do what? Live a life of integrity, honesty, decency. She didn’t say, go out and win every victory. But we have to be revolutionaries in the deepest sense. And revolution is about what? The sharing of power. Too many people are powerless: the sharing of resources. Too many people are poor: the sharing of respect. Too many people are disrespected: in the end, the sharing of love. Too many people don’t have love, brother. And that’s a life for each one of us in community, in struggle. And if the whole planet goes up, which it might—ecological catastrophe, nuclear catastrophe, as real as a heart attack—we did all that we could do. And people said, well, brother Nathan, you were true to your calling, my brother. Brother Cornel, you were true to your calling. That’s exactly right.

Transcript edited by Patrick Farnsworth.

Source: https://www.currentaffairs.org/news/cornel-west