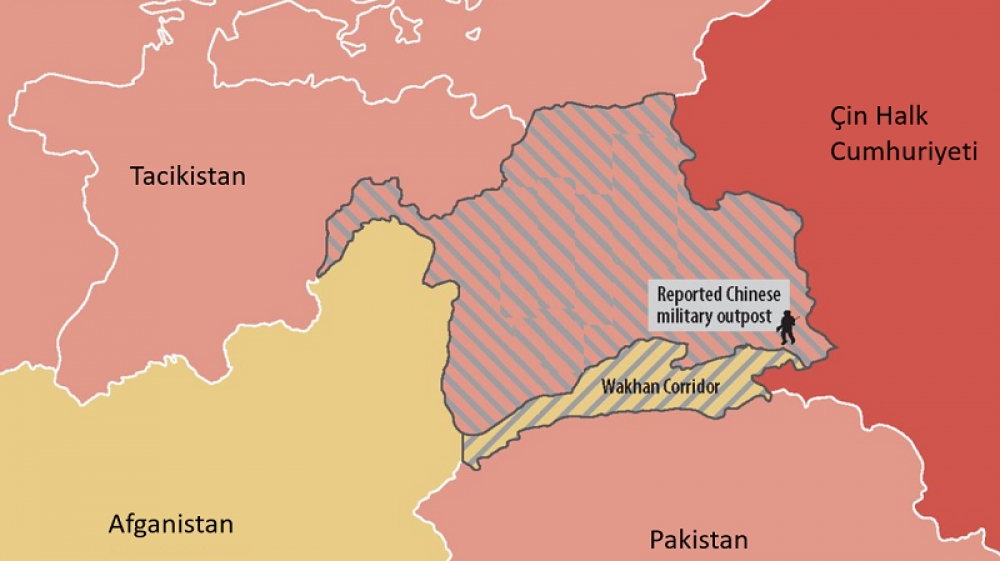

On August 21, the Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi landed in Kabul, after visiting India and Pakistan. The visit to Afghanistan holds significance as it comes after a gap of three years, the last being in March 2022. But far more consequential was the actual itinerary of the visit, notably a tripartite meeting with Pakistan and Afghanistan intended to address Chinese security concerns related to a narrow piece of land connecting China and Afghanistan, called the Wakhan Corridor. The Wakhan Corridor is a 350-km narrow piece of land, ranging from 10 to 50 km in width, which connects China’s Xinjiang Autonomous region and Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province in the northeast and is sandwiched between Tajikistan on its western side and Khyber Paktunwa, Gilgit Baltistan to the east.

While it is a fact that the Chinese have been investing in Afghanistan and have not shied away from the country since the Taliban takeover in 2021, Beijing has been cautious in its approach in dealing with the Taliban given that early investments have not been as lucrative as they hoped. According to a report published by the Stimson Center, Chinese investments have more or less remained at the same level since 2021, with imports from Afghanistan not growing in any substantial way. The same report claims that the Chinese investments in the Mes Aynak copper mine have not taken off, nor have investments in the Amu Darya oil fields. Despite these hurdles, the Taliban and Beijing are moving ahead on a plan to build a road through the Wakhan Corridor, connecting China and Afghanistan. According to Al Emarah English, which is the official mouthpiece of the Taliban government, the Wakhan Corridor road will be constructed in two stages, the first running 50 km from Bazai Gonbad in Little Pamir to the zero-point border with China, of which preliminary groundwork is complete with 60% of construction work currently underway as of March 2025. The second stage will cover 71 km, which is to be completed by the end of this year. Experts believe that once this road is complete, it will give China access to new markets in Europe through Afghanistan and at the same time, provide landlocked Afghanistan a new corridor to export and import goods directly with China.

Risk Factors along the Wakhan Corridor

Despite the potential for outsize economic benefits for China, Beijing has remained wary and reluctant to expedite the project due to security threats emanating from non-state actors. The Chinese foreign minister last week called for joint patrols and aggressive efforts to counter terrorism from the Taliban to address these threats. Beijing’s concerns stem from the presence of groups like East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) and the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP), both of which operate in Afghanistan and have mounted past attacks against Chinese interests in the region.

These concerns appear justified in light of the following:

Firstly, there is the persistent threat of the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM). ETIM is a Uygur separatist movement seeking the independence of the Xinjiang Autonomous region in China’s northwest. Southern Xinjiang is primarily populated by Islamic Uygurs while the northern part of Urumqi region consists largely of Han Chinese. The Uygurs claim that Xinjiang, which was once known as East Turkestan, is under illegal Chinese occupation. Hence, the East Turkistan Islamic Movement, which is also known as Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP), mounted numerous violent attacks through the late 1990s and the early 2000s. More recently, the Chinese government has clamped down on the movement, forcing them migrate to Afghanistan, where they have been sheltered by the Taliban, fighting alongside Al Qaeda. ETIM’s present leader Abdul Haq Turkestani was a member of Al Qaeda Shura council. ETIM has strong presence in Badakhshan province which is where the Wakhan Corridor originates. Since coming to power in 2021, the Taliban government has moved ETIM elements from Badakhshan further down south, yielding to Chinese pressure. However, recent reports suggest that ETIM may possibly be regrouping in Syria, Afghanistan, and elsewhere which will set off the alarm bells in China.

ETIM fighters consisting of ethnic Uygurs were dispatched to Syria by its top commander Abdul Haq Turkestani to fight alongside Al Nusrah Front, the predecessor of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which later became an indispensable part of that coalition. ETIM in Syria which is part of HTS coalition that overthrew the Assad regime, has been rewarded for this loyalty. HTS leader Abu Mohammad al-Jolani and the president of Syria have absorbed some of the senior ETIM commanders into the Syrian army. Al-Jolani promoted a top ETIM leader Abdulaziz Dawud Hudaberdi (‘Zahid’) to brigadier general in the Syrian army and also integrated Uygur fighters into the newly created 84th Division of the Syrian army. Its fighters are believed to be battle hardened with experience in maritime combat skills, including speedboat assaults, maritime rescues, and armed swimming and diving. Reports indicate that ETIM cadres operated a drone assault team called the Falcons against the Assad regime forces in Syria.

In Afghanistan, ETIM is believed to be expanding, with its ranks now numbering as high as 750. ETIM in Afghanistan is believed to possess anti-tank missiles, including BGM-71 TOW missiles. Given the success of its military intervention in Syria, ETIM has decided to “accelerate” its push for the independence of Xinjiang from China. In light of ETIM’s strength, ranging from 2000-3000 fighters in Syria, possible migration of battle-hardened fighters from Syria to Afghanistan would inevitably bolster the existing strength of ETIM in Afghanistan, which was reportedly discussed with the Taliban government in December 2024. Notwithstanding the above, ETIM has been on a tight leash by the Taliban, leading to defections and splinters, some joining the group’s archrival – the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP).

Secondly, Islamic State in Khorasan Province has mounted past attacks targeting Chinese interests, and the group has renewed its vow to mount such attacks in Afghanistan and elsewhere. In a message titled “Voice of Resistance” released in July 2025, ISKP called the Chinese “infidels” and “atheists,” claiming that Taliban is becoming too close to the Chinese, such that the only hope for Uygur Muslims is Islamic State. By directly calling out China’s oppression of the Uygurs in its message, ISKP has revealed its intention to recruit Uygurs and disenchanted ETIM Uygur fighters. It appears as though they have met with some early success in the effort. ISKP in October 2021 conducted an attack on a mosque in Kunduz, where the attacker was an ethnic Uygur. Following the incident, some Uygur fighters from ETIM may have switched sides to ISKP, given the Taliban’s stranglehold on ETIM in Afghanistan. At the same time, ISKP has ramped up propaganda targeting other Central Asian sympathizers from Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. ISKP’s official mouthpiece, Al Azaim, has started actively propagating, mainly in the Tajiki language targeting Tajikistan nationals. Reports indicate that ISKP is known to have conducted at least nine attacks since 2017, using Tajik nationals in Afghanistan, including one in Shahr-e-New area in Kabul in December 2022, injuring five Chinese nationals. Given these new recruitments and defections, ISKP’s strength appears to be somewhere around 2000 fighters in Afghanistan alone, constituted by Sunni Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Uygurs.

Thirdly and more importantly, it is believed that elements of groups such as ETIM, which are under the control of the Taliban, have clandestinely worked with ISKP and other smaller groups to mount attacks on Chinese interests. For example, it is believed that some elements of ETIM appear to have participated in the December 2022 attacks on Chinese targets in Kabul, conducted by ISKP. Reports indicate that ETIM and ISKP worked together in tracking Chinese nationals in Afghanistan, despite being otherwise opposed to each other. It has also been observed that ETIM and ISKP jointly published posters in the Uygur language in Afghanistan. This cooperation is not restricted to Afghanistan. ETIM and the Pakistan-based Jaish-al-Adl are believed to have jointly planned and executed attacks on Chinese interests in Pakistan as well.

Factoring in all of the above, China’s overriding security concern, that ETIM and ISKP pose a serious threat to its borders and nationals in Afghanistan, appears to be coming true. In January 2025, ISKP targeted and killed a Chinese national working in a mine near Tajikistan border, possibly the first ever Chinese fatality in Afghanistan from a terror attack perpetrated by ISKP. In July 2025, four Chinese nationals working in a mine were killed in the Badakhshan province, though this was not directly attributed to any terrorist group.

There are already indications that ISKP has relocated some personnel away from its core area of Kunar and Nangarhar, with factions migrating to Badakhshan. ISKP seems to draw strength from its Tajik members to conduct attacks, including the attack on a Chinese national in 2025 in Badakhshan which borders Tajikistan on the western flank of Wakhan Corridor. Similarly, Khyber Paktunwa in Pakistan, which abuts the eastern side of Wakhan Corridor, is a mine field for the Chinese with already multiple attacks taking place in the past orchestrated by Baloch separatists, including an attack in March 2024, killing five Chinese nationals. Add to this the possibility of ETIM defections and cooperation with ISKP and Chinese security concerns will only deepen.

When assessing development along the Wakhan Corridor, China must strike a balance between economic prospects and heightened geopolitical risk, creating an overall unenviable position in Afghanistan. The Chinese proposal to initiate joint patrols appears to be a cautious move to assuage its own internal concerns and those of its Afghan partners, albeit superficially. The resulting militarization of the region risks facilitating new clashes between global powers, with Afghanistan as the core once again in a repeat of the Cold War. There are already ominous signs in this direction as regional players like Pakistan attempt to move in on the deal. And not surprisingly, US support for Pakistan amid the current India-Pakistan conflict is a contemporary reflection of the position Pakistan once enjoyed during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. These emerging scenarios may be worrisome to India, as integrating Pakistan occupied Kashmir (POK), including Gilgit Baltistan which borders Wakhan Corridor under the occupation of Pakistan, moves further out of reach.

Source: https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/chinas-wakhan-corridor-dilemma-economic-development-or-security/