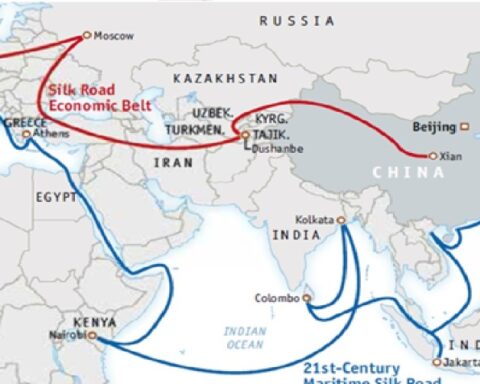

The rapid ascent of China and its increased presence in South and Central Asia, as well as in the Indian Ocean, have increased the risks of the Sino–Indian rivalry.

The security threats of the Sino-Indian rivalry are sharpened by each country’s strategic partnerships: India with the US; and China with Pakistan, which is also India’s traditional adversary. The authors note that Indian elites regard China as India’s principal rival, ranked above Pakistan, whereas Chinese elites regard India as a lesser rival than the US and Japan.

The authors argue that the Sino-Indian rivalry started almost immediately after the two countries’ emergence into the global arena in the 1940s. India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, tried to promote India as the natural leader of Asia, a role that was contested by China. And the rivalry takes two forms: spatial rivalry, including disputes over borders and territory; and positional rivalry, related to each country’s position in the regional pecking order. The authors believe that positional rivalry may be more consequential in the Sino-Indian relationship.

China gradually chipped away at India’s ambitions. India inherited from Britian the notion that Tibet served as a good buffer for keeping hostile armies away from the northern Indian border. But when China occupied Tibet in the 1950s, India was too weak to challenge it. India was further weakened by the 1962 Sino-Indian War, when its army was beaten by China. Despite the territorial aspect, the authors believe this war to have been an important mark of the positional rivalry.

India became a marginal strategic player in Asia for the rest of the twentieth century. And with China’s rapid economic development, the material power gap between China and India only became more substantial.

The authors argue that the frequency and intensity of Sino-Indian crises have only increased over the past decade. The book discusses four significant militarised border disputes since 1962: the 1967 Nathu La Crisis; the 1986–87 Sumdorong Chu Crisis; the 2017 Doklam Crisis; and the 2020 Ladakh Crisis. They believe it entirely possible that future border crises may spiral into inadvertent wars.

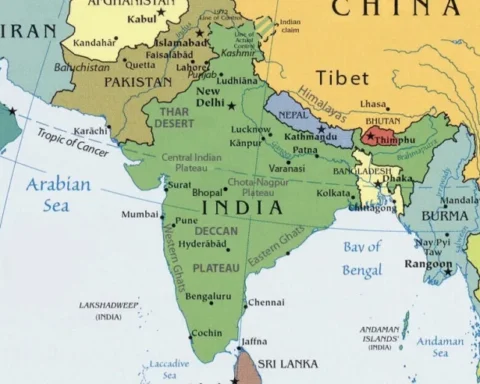

Factors driving conflict between the two countries include India’s growing strategic alignment with the US, such as through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, and Chinese militancy under the leadership of Xi Jinping. Today’s world differs vastly from that of most of the postwar period, during which US policy favoured relations with Pakistan, rather than India. China has also argued that inherited colonial borders are not sacrosanct and are subject to revision—as reflected in its claim to the entire Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh.

Beyond these crises, the authors argue that China has been working to narrow India’s strategic space by penetrating its neighbourhood. China is rapidly transforming Pakistan into its strategic surrogate in South Asia, notably through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor of the Belt and Road Initiative, which passes through territories claimed by India.

Another factor has been Chinese investments in ports across the region, particularly those in the Indian Ocean. These include investments in Cambodia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and the Maldives. Countries such as Nepal and Bangladesh can also exploit Chinese interest to undermine India’s natural predominance in South Asia. As such, the Sino-Indian rivalry shows no signs of abating, if anything it seems to be intensifying.

The authors also look ahead to the prospects for increasing rivalry, notably the risk of possible water wars. As most of the major rivers in South and Southeast Asia have their origins in Tibet, China controls the sources of many Asian rivers, including five in India—the Indus, Brahmaputra, Sutlej, Kosi and Ghaghara. India and China already face water scarcity, which will only worsen in the future. Another looming risk is the security of energy supply, much of which is imported via maritime routes in the Indian Ocean.

* John West is the author of Asian Century … on a Knife-edge and executive director of the Asian Century Institute. His career has included major stints at the Australian Treasury, the OECD, the Asian Development Bank Institute and Tokyo’s Sophia University.

Source: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/bookshelf-risks-of-sino-indian-rivalry-set-to-grow/