Interview: Jonas E. Alexis

with Nicholas Kollerstrom

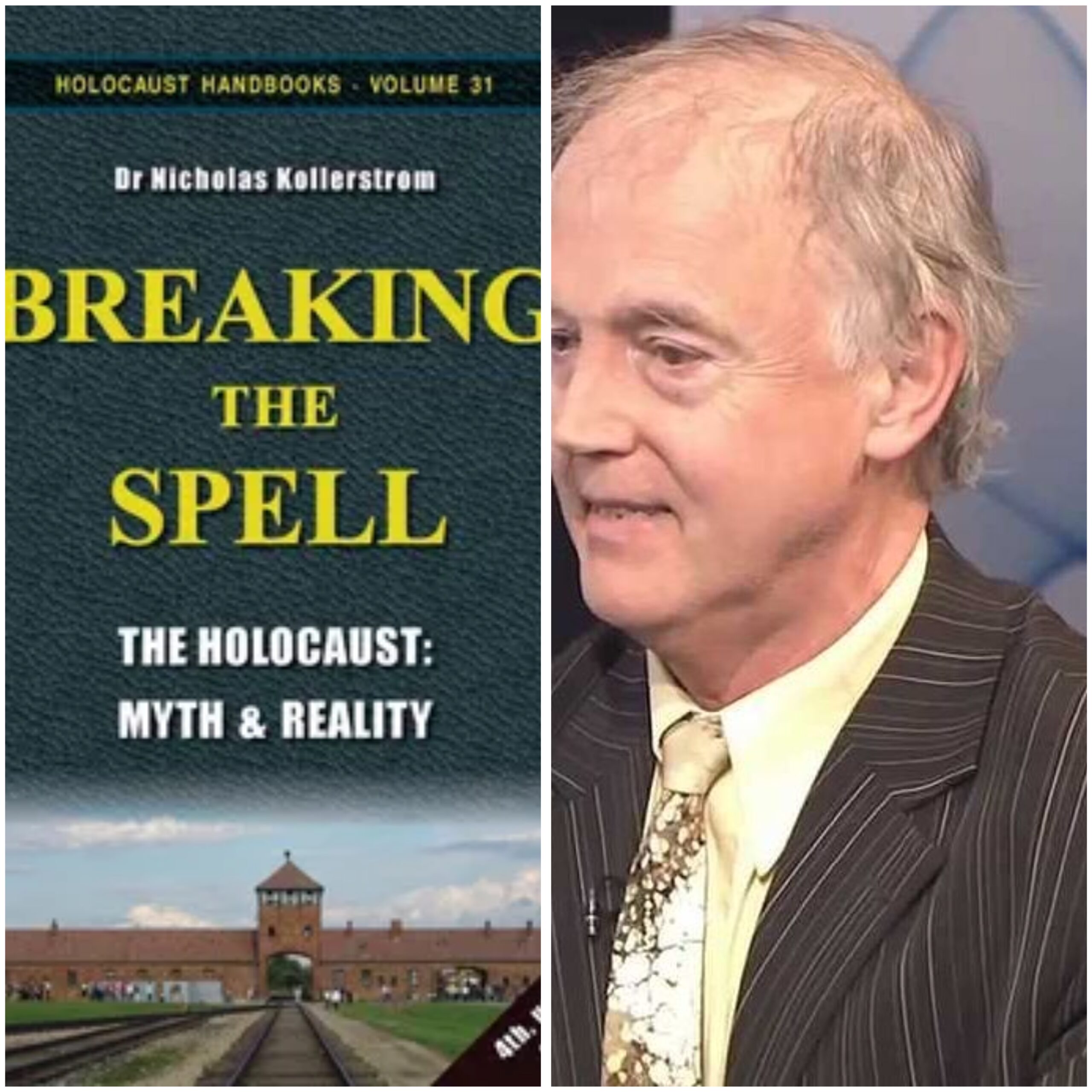

Nicholas Kollerstrom holds a B.A. in the natural sciences from Cambridge University, with a focus on the history and philosophy of science. He later earned a Ph.D. in the history of astronomy from University College London. He has also worked as an astronomer and was formerly a correspondent for the BBC. In addition, he received grants from the Royal Astronomical Society for his research on the discovery of Neptune.

Kollerstrom has written numerous technical articles and essays.[1] He is the author of Newton’s Forgotten Lunar Theory: His Contribution to the Quest for Longitude (London: Green Lion Press, 2000) and The Metal-Planet Relationship: A Study of Celestial Influence (Eureka, CA: Borderland Sciences Research Foundation, 1993). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers originally included several of his entries on figures such as the mathematician and astronomer John Couch Adams (1819–1892), the astronomer John Flamsteed (1646–1719), and Isaac Newton. However, after Kollerstrom publicly challenged the orthodox Holocaust narrative using scientific and historical arguments, all of his contributions were subsequently removed from the encyclopedia.

Kollerstrom was widely cited in the scholarly literature[2] until he began examining the chemical evidence surrounding the use of Zyklon B during World War II. After publishing his findings, he became a target of professional backlash. Graham Macklin, manager of the Research Service at the National Archives, publicly dismissed Kollerstrom’s claims—particularly his references to the swimming pool at Auschwitz-Birkenau and to the orchestras reportedly available to inmates.[3]

Macklin, as a defender of the institutional consensus, did not attempt to investigate or refute the claim on evidentiary or logical grounds, since doing so might have risked his academic reputation. Instead, he chose the easier route: mockery and dismissal. Yet Kollerstrom was not the first to make such observations. Individuals who were actually present at the camps made similar statements, and their testimony is part of the historical record. Historian Paul Berben, who interviewed numerous survivors after the liberation of the camp and conducted extensive archival research, records this in Dachau: The Official History: “A few sporting and cultural activities were authorized. Officially the S.S. could no longer maltreat the inmates as they liked. But the disciplinary regime remained very harsh.”[4]

Even “money brought on arrival and any that was subsequently sent to a prisoner was credited to him, and he could only draw 15 R.M. monthly. As some prisoners had considerable sums of money, especially in the early years, the S.S. conducted profitable financial transactions. When in 1942 the system of ‘gift coupons’ was instituted, the prisoners could no longer have money in their possession. The money in their account had to be used for the purchase of articles obtainable at the canteen, another course of considerable profit to the camp administration.”[5]

Berben notes that “theatrical entertainments, concerts, revues, and lectures were arranged too. Among the thousands of men who lived in the camp, there were all sorts of talents, great and small, to be found: famous musicians, good amateur musicians, theatre, and musical artists. Many of these men devoted their time in the most admirable way to gain a few moments of escape for their comrades in misery and to keep up their morale. And these activities helped too to create a feeling of fellowship.”[6]

The following detail may be surprising to many readers:

“The camp had a library which started in a modest way but which eventually stocked some fifteen thousand volumes. It had been formed with the books brought in by prisoners or sent to them by their families, or from gifts. There was a very varied choice, from popular novels to the great classics, and scientific and philosophical works. Only books in German and at the most a few dictionaries were allowed, but there were some ‘forbidden’ volumes there too, whose bindings had been camouflaged by the prisoner-librarians and which received particular attention from those who were ‘in the know.’

“The intellectuals in the camp kept the catalogs up to date and were in charge of lending out the books. Unfortunately, it was not possible for more than a very few prisoners to do any reading, so it was mainly only those lucky enough to be attached to the library who benefited from it. Yet it is astonishing to learn that some men in spite of their miserable convicts’ existence nevertheless found the energy to take an interest in the arts, in science, and in philosophical problems.”[7]

In addition, letters sent to individual families “had to be written in German and to one single recipient. Contents had to deal only with family matters and no reference at all was permitted to live in the camp, or the letter was not sent off.”[8]

During the last few years of the war, “it was decreed that a prisoner could send or receive two letters or two cards per month. He had to write in ink, very legibly, on the fifteen lines of each page of a letter. His correspondent could only use plain paper, and double envelopes were not allowed.”[9]

Jewish historian Sarah Gordon corroborated many of these claims in her 1984 study published by Princeton University Press.[10] Taken together, these facts raise a serious question: can popular historians, in good conscience, continue to disregard this evidence and persist in advancing one incoherent assertion after another without critical reflection?

If Plato is correct that “having a grasp of the truth is having a belief that matches the way things are” and that “being deceived about the truth is a bad thing,”[11] then how are scholars and intellectually serious individuals to pursue truth if they are discouraged—or effectively prohibited—from asking deeper questions about the past? Were we not taught from an early age that the scientific enterprise begins with fundamental questions? Were our science instructors misleading us when they introduced us to the scientific method? Likewise, did our history teachers deceive us when they urged us to consult archives, examine original documentation, and identify contradictions in the historical record?

Furthermore, one may reasonably ask whether figures such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, or Kant could even find intellectual footing in the twentieth or twenty-first century—an era in which restrictive speech codes pervade both Europe and the United States, and in which many academics are apprehensive about speaking openly on certain historical questions, particularly those concerning events in Nazi Germany[12] Would such thinkers not be pressured to silence themselves, to set aside rational inquiry, and to abandon philosophical critique? Would what Norman Finkelstein has termed “the Holocaust industry” not immediately move to delegitimize, marginalize, or metaphorically exorcise such dissenting intellectual voices, much as if Kant’s critique itself were a demon to be expelled from Prussia?

Those are some of the questions that will be explored in the following interview with Nicholas Kollerstrom. Kollerstrom recently sent me his new work, The Dark Side of Isaac Newton: A Modern Biography, which I have not yet had the opportunity to read but plan to begin at the end of December of this year.

JEA: Let’s start with a statement from your book, Breaking the Spell: The Holocaust—Myth & Reality. You write:

“The fastest way to get expelled from a British university is by saying you are looking at chemical evidence for how Zyklon was used in World War II, with a discussion of how delousing technology functioned in the German World War II labour camps. This is considered to be absolutely forbidden. How strange is that? After being a member of my college for 15 years I was thrown out with one day’s warning, having been given no opportunity to defend myself, a fact announced on its website. What I had done was so terrible that it could not announce what my crime was: I felt like Faust caught making his pact with the devil.”[13]

This situation is intellectually mind-boggling. Do scientists not pride themselves on seeking rigorous evidence? Do academic institutions, such as University College London, not uphold the principles of free inquiry, particularly when the individual in question is a recognized scholar? Were the methods of scientific investigation employed when examining the historical use of Zyklon during World War II? If so, why did the academic community respond with such hostility? Were inquiries made into whether your work was being judged as a transgression against academic norms?

NK: I guess it was just too much for them to handle. I was a science historian in the ‘Science and Technology Studies’ department at UCL in London, Britain’s 3rd oldest university, which was supposedly set up on a secular basis, so that there would not be any inquisition about the private beliefs of its members of staff.

But I had to realize that belief in ‘the Holocaust’ is nowadays some sort of religion, it’s the one thing that academics are not allowed to doubt or criticize. They put up on their UCL website that they were totally opposed to what I was doing, but did not say what the terrible thing was! There was just silence from my colleagues or rather ex-colleagues and I had to realise that I’d never get another paper published in an academic journal.

Sure I was using the scientific method, I was comparing and critiquing two different published surveys of residual cyanide in the walls of German WW2 labor camps. They both used much the same method of analyzing the cyanide so I pooled the two data sets together. This gave about forty measurable samples which is quite a decent sample. What was puzzling was that in all the media damnation that ensued, no one was interested in what I’d actually done, in the basic chemistry, it was just ‘We’ve found a Nazi!’

JEA: Serious scientists, such as yourself, are consistently engaged in the pursuit of truth, asking probing questions and carefully evaluating evidence to provide accurate explanations of available data and contested issues. Once competing hypotheses have been considered, one should then draw inferences to the best-supported explanation.[14] Do you believe that some individuals hesitate to examine the evidence because it might challenge their preconceived notions? To what extent, in your view, are certain actors manipulating or selectively presenting facts to serve particular agendas?

NK: You have well described what the scientific method is supposed to be. I believe what is going on here is a clash between science and religion, where ethically-damned Revisionists are trying to look at scientific evidence to reconstruct the past and Holocaust legislators wish to ban any doubt over their official narrative. My wish here is that some kind of forum could exist where different views of what happened in WW2 could be discussed. If we don’t believe in the rational debate then we’re lost.

You might suppose that science historians could discuss say hygiene delousing technology prior to DDT. You might suppose that is obscure enough to be a non-explosive topic. DDT started to be widely used after WW2 for this purpose. Before that, for, say, forty years Zyklon delousing chambers were the normal way of doing it. It was normal hygiene technology for killing bugs in clothing and so on. So no one’s allowed to discuss this, because that would violate the new religion, because it would soon end belief in the huge human gas chambers that existed only in WW2, only in Poland.

JEA: Scientists and academic professionals are expected to maintain a healthy skepticism toward claims, assertions, and even primary documents, evaluating them against a range of sources in order to corroborate evidence and, where necessary, challenge prevailing interpretations. When documents reveal contradictions or call into question our preconceived understandings, it becomes essential to pause and critically reassess our worldviews to determine whether they are grounded in evidence or merely reflect popular opinion. Why, then, does the so-called Holocaust establishment appear reluctant to scrutinize the metaphysical assumptions underpinning its framework?

The first principle in the examination of any scientific or historical claim is the affirmation that truth exists—even if its full contours are not immediately known to the investigator. Without this foundational premise, the scientific enterprise collapses into futility, for there would be no point in gathering data, formulating hypotheses, testing theories, or arriving at what we call scientific “facts.” This raises a further question: do those within the Holocaust establishment actually affirm that truth exists in an objective and discoverable sense? Do they regard truth as something to be pursued rigorously, while fabrications, exaggerations, and large-scale distortions are to be exposed and rejected?

Over the years, I have engaged a number of academics on this issue, and I have been struck by the realization that not a single one of them appeared genuinely committed to serious scholarly inquiry, despite their public insistence—often in print—that evidentiary rigor matters. In one case, a scholar refused to grant permission for our exchange to be published, on the grounds that doing so would undermine claims he had previously presented in a book—ironically issued by the University of California Press.

NK: I reckon they, i.e. people in the Holocaust establishment, believe that truth is what they want to believe.[15] They will always endeavor to undermine historical-factual debate about What Really Happened with claims about alleged emotions, of love or hate, such as: ‘You are just an anti-Semite’, or ‘You really hate …’ Whatever. Or they will claim to be hurt.[16]

My colleague Richard D. Hall who does ‘RichPlanet’ recently wrote to various different Jewish ‘Holocaust groups in the UK which are especially concerned with ‘Holocaust education – and that is big business over here – asking if they could provide anyone who could debate the issue, but none of them would. The professional skepticism of scientists just goes right out of the window where this topic is concerned I’m afraid.

I agree with you totally about the mental enslavement which academics here display. For example, a few years ago a team from Britain’s University of Birmingham science department went to Treblinka with ‘ground penetrating radar equipment. They didn’t find a single gassed body, or any bodies under the ground come to that, no gas chambers, zilch. No wait, they found some shark’s teeth in the ground.

This was promoted by the British media as having confirmed the canonical story that eight hundred thousand people mainly Jews had been gassed using diesel exhaust in that transit camp. Was the British scientific establishment bothered that diesel exhaust is not actually lethal and couldn’t have gassed anyone? No, evidently not.

Or, to give a US example, Elie Wiesel’s Night (which has supposedly sold twelve million copies) has been used in many ‘Holocaust study courses in American universities. That features the primary Holo-image of burning piles of human corpses. They are just set on fire, and they burn. Why has not the US Society for Advancement of Science protested at such nonsense being taught in universities?

JEA: I recently read Nick Cohen’s article in The Guardian about you and was astonished by a number of the claims he advanced. He titled the piece, “When academics lose their power of reason.” But is an academic truly “losing” his capacity for reason simply by asking probing and intellectually serious questions?

Cohen quotes the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who observed that “as to the evil which results from censorship, it is impossible to measure it, for it is impossible to tell where it ends.”[17]

He then adds, somewhat rhetorically, that “admittedly, if the philosopher had lived long enough to hear the conspiracy theories of the 21st century, even his defense of free speech might have weakened.”[19]

It is far more plausible that Bentham would have been astonished to discover that what now passes as the “Holocaust establishment” functions as an impediment to serious scientific, historical, and rational inquiry—precisely because genuine scholarship is grounded in rigorous evidence, not in ad hominem attacks, straw man arguments, or the facile dismissal of dissent as “conspiracy theory.” Would you agree with this assessment? It is doubtful that Cohen has taken the time to engage seriously with your actual work on these matters. Indeed, as you state quite reasonably in your book, “We need to find out how to discuss [the ‘Holocaust’] calmly, how to respect different viewpoints, and what are the primary sources we should be consulting.”[20]

NK: Sure. I got vilified by Nick Cohen in The Observer right after being chucked out of my College – having been in it for fifteen years – and discovered that I was allowed no right of reply. The Observer thereby put a death wish against me by allowing Cohen to say I needed to be stuffed and put next to Jeremy Bentham (his stuffed body is on display at UCL).

As you note, Cohen was there dismissing conclusions drawn from measurements of cyanide in the walls of the German labor camps as a ‘conspiracy theory.’ He used an effective form of discourse designed to terminate debate and replace it with a fairly simple emotion – hate. A lot of people hated me after I’d been through all this, and that was a new experience.

JEA: You wrote:

“After somewhat over a decade of quiet academic research, my life changed rather abruptly as I became ethically damned, thrown out of polite, decent groups, banned from forums, and denounced in newspapers, with half my friends not speaking to me anymore—while the other half still would be provided I kept off ‘that awful subject.’ So as a philosopher I was granted an unusual and excellent opportunity to ponder the difference between what is real and what is illusory. I should be grateful to my fellow countrymen for absolutely refusing rational debate on this topic, for insisting on my silence over it, and for transforming the discussion into an insult. I know what I have been through. I have been well-cooked…The damnation cast upon me was ostensibly political…Going into my local, or even my gym, I felt as if some Mark of Cain had been branded onto my forehead.”[18]

You further observed that “no one seemed interested in what I had actually done, namely synthesize a couple of chemical investigations concerning residual wall-cyanide taken from World War II labor camps.”[19]

This is, by any fair standard, the work of a serious researcher engaged in empirical inquiry. What kind of investigation, then, do you think the Holocaust establishment was expecting? Have you ever asked its representatives what form of evidence or scientific methodology they would regard as acceptable?

NK: Plato’s metaphor of the Cave seems to have suddenly become very relevant in the 21st century. He there described how people were chained to see just the flickering images on the wall, which they mistake for reality. They become furious with any persons who come from the above-ground world who try to tell them about it and seek to destroy them. We surely have to believe – as you Sir have tried to show in various articles – in some sort of Logos principle which means that we can by debate find together by logic whatever the truth is.

I think that the ‘Holocaust establishment’ is concerned to promote stories, of alleged ‘Holocaust survivors. We need to bear in mind the catastrophic situation that has here developed, where the German government has been paying and continues to pay anyone who claims to be such a Holocaust survivor.[20] That is a very strong motivation for memory enhancement, shall we say. These people then go to schools. Their ‘memories’ are promoted by the Establishment, and anyone who challenges the accepted wisdom gets ethically damned.

The UCL I would want to have belonged to would have had a detailed debate about brick and wall absorption of cyanide gas, the nature of the ferrocyanide complex and when it turns blue, and whether it remains permanently in the brick. It would have commissioned a new investigation to go and visit Birkenau-Auschwitz and chip away some further brick samples, and used the very latest chemical-assay procedures for measuring the cyanide. But, maybe that only happens in some parallel universe….

Notes

[1] See for example Nicholas Kollerstrom, “John Herschel on the Discovery of Neptune,” Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 9(2), 151-158 (2006); “Decoding the Antikythera Mechanism,” Astronomy Now, Vol. 21, No. 3, 32–35, 2007; “The Case of the Pilfered Planet: Did the British steal Neptune?,” Scientific American, December 1, 2004; “Overview/Neptune Discovery,” Scientific American, November 22, 2004.

[2] See for example William L. Harper, Isaac Newton’s Scientific Method: Turning Data into Evidence about Gravity and Cosmology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 65, 162; Nicholas Campion, A History of Western Astrology, Volume II: The Medieval and Modern Worlds (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2009), 310; James Gleick, Isaac Newton (New York: Vantage Books, 2004), 226; Roger Hutchins, British University Observatories 1772-1939 (New York: Routledge, 2008), 91, 94, 105, 117, 155, 156, 158, 460, 467.

[3] Nigel Copsey and John E. Richardson, eds., Cultures of Post-War British Fascism (New York: Routledge, 2015), 190.

[4] Paul Berben, Dachau: The Official History (London: Norfolk Press, 1975), 57.

[5] Ibid., 60.

[6] Ibid., 72.

[7] Ibid., 72-73.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 73.

[10] Sarah Gordon, Hitler, Germans, and the Jewish Question (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984).

[11] Plato, The Republic (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 116.

[12] Kant and others have already been labeled anti-Semites. Paul Lawrence Rose, Revolutionary Antisemitism in Germany from Kant to Wagner (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990).

[13] Nicholas Kollerstrom, Breaking the Spell: The Holocaust—Myth & Reality (Uckfield, UK: Castle Hill Publishers, 2014), 9.

[14] See for example Peter Lipton, Inference to the Best Explanation (New York: Routledge, 1991); Susan Haack, Evidence Matters: Science, Proof, and Truth in the Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014); Christopher Behan McCullagh, Justifying Historical Descriptions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

[15] For a fairly good treatment on this, see Daniel J. Flynn, Intellectual Morons: How Ideology Makes Smart People Fall for Stupid Ideas (New York: Crown Forum, 2004).

[16] For scholarly treatments on the anti-Semitism issue, see for example Norman Finkelstein, Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History (Berkley: University of California Press, 2005 and 2008); Albert S. Lindemann, Esau’s Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997); Bernard Lazare, Antisemitism: Its History and Causes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995).

[17] Ibid.

[18] Kollerstrom, Breaking the Spell, 15 and 16.

[19] Ibid.

[20] For studies on this, see for example Norman Finkelstein, The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering (New York: Verso, 2000); see also Nir Gontarz, “Israeli Diplomat in Berlin: Maintaining German Guilt About Holocaust Helps Israel,” Haaretz, June 25, 2015.

Source: https://www.unz.com/article/astronomer-and-historian-of-science-examines-the-holocaust-industry/