As the New Syria enters 2025, Turkey has ample reasons and opportunities for a fresh start. As long as politics realizes that by the end of 2024, a new global and regional wave is inevitable and that it must enter 2025

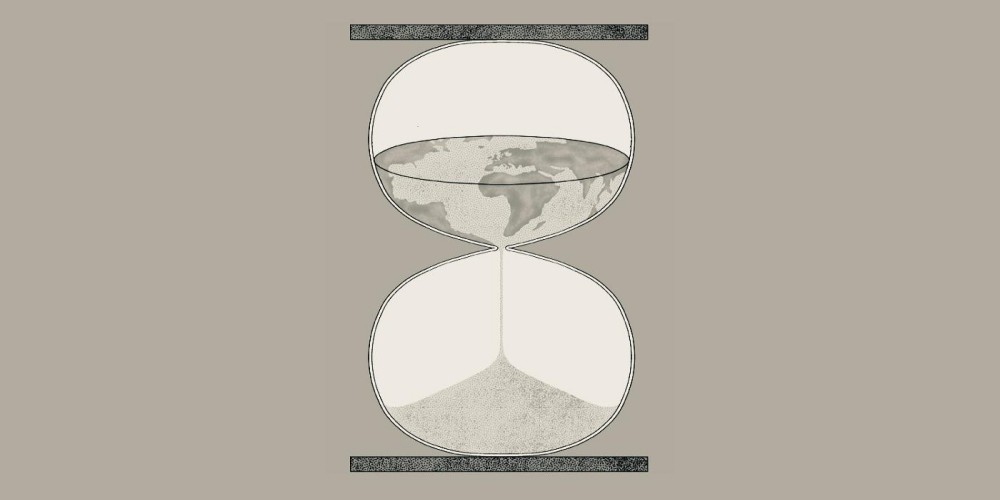

We have entered the final year of the first quarter of the 21st century. While this first quarter has been relatively calm for the world at large, our region has become the epicenter of geopolitical tensions. From Afghanistan to Iraq, Syria to Russia, invasions, civil wars, coups, and the ongoing genocide in Gaza have turned the region upside down. Though it has been 25 years since the dawn of the 21st century, our region continues to suffer from the unhealed wounds of the 20th century. While the calendar progresses through the 21st century, we remain burdened by the struggles of a region whose politics are still lost in the 20th century. Türkiye, too, is not immune to these struggles. From this perspective, making assessments and predictions for 2025 becomes both a challenging and anxiety-inducing effort. On the other hand, the past year concluded with such evident developments shaping geopolitical and economic directions that the framework for 2025 projections has already been outlined.

It is said that the renowned physicist Bohr once remarked, “Making predictions is very difficult, especially about the future.” Whether Bohr actually said this or not is uncertain. However, what we do know is not only that making predictions about the future is challenging but also, as a modern Russian proverb suggests, that “the past has become harder to predict than the future.” In some countries, predicting the past is more significant and difficult, while in others, projecting the future is a more complex endeavor. In some cases, both are equally challenging. For instance, like us, Russians suffer from both their past and their future. As Svetlana Alexievich summarizes the situation in an anecdote from Secondhand Time: “In Russia, everything can change in five years, but in two centuries, nothing changes.” Indeed, we frequently encounter scenarios where manipulating the past seems easier than constructing and predicting the future. As we fail to escape our self-imposed prisons to confront the burdens and challenges of the future, we become increasingly active in the passive realm of the past.

Edmund Burke, writing about the French Revolution, stated that society “does not arise merely from a partnership among the living but also includes a relationship between the dead, the living, and those yet to be born.” We, however, have yet to resolve our issues even among the dead, let alone between the living and the dead. One might even say that the “record books” of almost none of the deceased are truly closed. After all, the most lucrative areas for political reconstruction and profiteering remain our cemeteries. Our political speculators are well aware of this, which is why they still prefer “investments in the dead.” Our hope is that if we can somehow resolve this issue, we might develop the resolve to address matters concerning both the living and future generations. To envision 2025 and beyond, we first need to fully confront the present. Yet, we remain trapped in a series of anachronistic crises, endlessly debating our place in the world, who we are, and who we ought to be—right down to drafting yet another interminable social contract.

Türkiye’s unfinished 20th century

It is evident that, with our internal dynamics and a century-long suppression of societal and state intellect, we have managed to produce the current picture before us. We possess plenty of issues that waste the energy needed to achieve a sustainable democratic momentum, for better or worse. We are effective in determining, through elections, who will govern us. In this regard, we perform well. With a peaceful and civil “war of choice,” we make our decisions with the overwhelming participation of the public. There is even a strongly established consensus on who should not govern us. However, we show little interest in how we should govern and be governed. Yet, the nature of the state directly determines the depth of our democracy.

As we complete the years leading to the second century of the Republic, we are aware—when we are honest with ourselves—that, mentally, we remain somewhere in the first half of the 20th century. Physically, in the 21st century, we live under the burden of the past, in a strange refugee-like psychological state. Those who live in this “refugee” state within a cultural world often hold a deep belief that their 21st-century exile will end one day, allowing them to return to the “golden age” of the 1920s, their “nostos,” their homecoming. We continually postpone facing these traumas and their manifestations across various groups, caught in the pains of historical synchronicity. Yet, at some point, we must achieve a certain level of historical justice. It is impossible to move into the second century of the Republic without transcending the identity fragmentation caused by those who mold the past like clay, exhausting today with the tension between heroes and traitors. Simply put, we will not reach the beginning of a sustainable democracy. As Burke beautifully articulated, there is no realistic solution other than crowning the relationship between “the dead, the living, and the unborn” with a healthy social contract.

The written “social contract” we currently have fits us as poorly as an ill-fitting shirt. Our democracy, suffocated by invisible bans, fears, and taboos, is exhausted. For this reason, it barely has the strength to conduct elections. For anything beyond this, we need a fully democratic constitution, a sound legal system, a transparent and efficient public administration, fair income distribution, a civil society capable of standing without state support, companies that won’t collapse without public funding and privileges, and independent media and universities. Everyone knows the king is naked. Yet, the fear of change is so immense that they watch helplessly as a system in which those who proclaim the king’s nakedness are silenced continues to limp along. All actors have grown so accustomed to this state of affairs that “politicophobia” has become the dominant fear by far. In the midst of this crisis, answering the question of what will happen in 2025 is not easy. Yet we are not entirely without material. At least now, we know that we are entering a world shaped by Trump and a region free of Assad.

A world led by Trump and a region without Assad will pave the way for far greater structural ruptures than anticipated. Biden, despite being an unwanted figure due to the shocks of COVID and Trump, created the illusion that he interrupted or slowed the disruptions that began in 2017 by splitting the Trump years. Yet Biden continued Trump’s trade wars, deepened America’s geopolitical aimlessness, and became a fervent supporter of Israel’s genocide in Gaza. Now, we are entering a recklessly anticipated second Trump era. Assad, too, found breathing room during Trump’s presidency with support from Russia and Iran. Until two months ago, there was a prevailing assumption that Syria’s revolutionary process had been halted and that the Assad-led status quo had solidified. However, 2024 demonstrated that both narratives are far from over. In hindsight, 2024 will likely be understood as the beginning of the end for many key developments. Perhaps the true “end of history” that Fukuyama has been waiting to see finalized since 1992 came in 2024 with Trump’s re-election. The revival of the paralyzed limbs of liberal apoliticism, which has poisoned humanity’s hard-earned democratic experience, has now become a distant possibility. This will undoubtedly mean significant structural disruptions for the world. For Türkiye, it might finally present an opportunity to transition from the past to the future. Unexpectedly, 2024 saw renewed momentum both within Türkiye and beyond its borders in addressing the Kurdish Issue, which was thought to have been frozen, 40 years after the PKK’s first terrorist act.

Politics in Türkiye after Syria

Türkiye now faces the reality of Syria. In the near future, the risks and opportunities for Turkish foreign policy and geopolitics will primarily take shape around the Syrian context. Similarly, domestic politics will also operate on this same ground. This situation presents a clear advantage for the government. If things deteriorate in Syria, the government will naturally stand out as the trusted actor capable of managing the risks directed at Türkiye. If things go well, the government will already reap the benefits. In both scenarios, the government’s advantage stems not from its own brilliance but from the opposition’s positioning. The opposition must first rid itself of the alienated perspective shaped by fears in a world of perceived threats to Türkiye and instead learn to view the region through a Türkiye-centric lens. With this knowledge, it needs to build a positive geopolitical narrative and persuade the public. Whether it can navigate this challenging course remains uncertain. What is clear is that, regardless of when the next elections are held, all political actors will have to operate on a political trajectory centered on Syria until that day.

More importantly, the dismantled order in Syria is, in many ways and through certain codes, quite familiar. For those clinging to these codes despite the collapse of Baathism, Syria offers a profound and genuine opportunity for confrontation, whether they want it or not. Attempts to artificially sustain, in Türkiye, the historical anomaly that has ended in Syria will lead to nothing but political futility. It is crucial for them to realize this.

The troubles of the opposition do not leave the government without concerns. In fact, the government’s burden will visibly increase in the coming years as the risks emerging post-Syria combine with global ruptures. This burden will likely exert pressure through two main dynamics initially. First, challenges regarding the Kurdish Issue and the PKK are expected. In an atmosphere where politicophobia has long become the dominant narrative, the striking roadmap proposed by the most unexpected figure remains suspended. Bahçeli, in his characteristic manner and rhetoric, voiced the resolution of the issue months ago in the most firm and eager terms. He has not stepped back from this position and continues to follow up on it every week. The initiative he started before the Syrian revolution gained even more meaningful and authentic potential after Assad’s fall, and the ground for taking steps has become even more favorable.

The cost of politicophobia

Despite all these developments, it is still impossible to claim that the fear of politics has been eradicated. As long as both government and opposition actors fail to overcome their fear of politics, it will be extremely difficult for them to carry out a coherent process on the country’s most pressing issues. A closer look at the initial reactions to Bahçeli’s proposal reveals that, rather than acknowledging the century-old problem he pointed to—one that everyone is aware of—many opted to discuss the nature of the “finger” doing the pointing. This evasion makes it clear that the core issue is politicophobia. Simply imagining a Türkiye without the Kurdish Issue or the PKK is enough to understand who and what would be rendered irrelevant, as well as the fears this creates. Those who recognize that Bahçeli’s courage to overcome this fear leaves them exposed cannot hide their frustration either. The disruption of the comfort provided by long-familiar and rehearsed roles, combined with the pressure to produce genuine political solutions, is ultimately a positive development for 2025.

Additionally, some fundamental elements of the future vision Türkiye has outlined and proposed for Syria are equally applicable to Türkiye itself. We should not find ourselves in a position where we hope for success in areas like constitutional reform or fostering a will for coexistence in Syria, while failing or hesitating to take those very steps for ourselves. Such contradictions are unsustainable. In essence, Türkiye’s current 20th-century political status quo is incompatible with achieving a more prosperous and effective place in the 21st century.

The second key issue is the risks posed by global geopolitical ruptures. The economic and geopolitical landscape, which will be directly impacted by global trade wars, is bound to come under significant pressure. Türkiye’s economy, already battered by eight years of double-digit inflation averaging above 30%—a result of the democratic erosion that began post-2016 and was compounded by COVID—finds itself at a challenging juncture as these risks emerge. Yet, the global trade war could also offer Türkiye significant opportunities. Whether these opportunities are seized depends entirely on Türkiye’s choices. There is an almost perfect yin-yang relationship between Türkiye’s democracy, its economy, and its geopolitical power. As Türkiye’s democracy deepens, its economic strength and geopolitical influence also grow. Ankara must quickly and earnestly take steps in two interconnected areas, considering the global inflation and trade wars that Trump is expected to exacerbate. On one hand, there is a need for a genuine democratization and reform process. On the other hand, a new positive agenda must be built with the EU on geopolitical, economic, and security grounds. Both are not only feasible but also essential.

Polanyi’s The Great Transformation and Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom were published in the same year, 1944. In his book, Polanyi argues that humanity cannot endure a completely free market system for long. It is now evident that the 40-year appetite for liberal democracy has waned. The likelihood of a global retreat from democracy in 2025 and beyond has increased significantly. From the United States to China, Russia to India, Brazil to Mexico, and Pakistan to Iran, nations have tools and resources to compensate for the democratic erosion—or even its complete absence—that seems inevitable. Türkiye, however, has neither the long-term economic resources nor the political tradition to offset its democratic shortcomings, unlike these countries. For Türkiye to excel in every area—from geopolitics to technology, education to per capita income—it must first close its democratic deficit.

Just as everyone enters the New Year sequentially according to their respective time zones on December 31st, nations do not enter centuries simultaneously in political, economic, and social terms. Some enter centuries decades later, while others may take more than a century. For Türkiye to secure a reasonable place in this ranking, it now has a genuine opportunity. At least in 2025, global and regional dynamics are set to exert pressure in this direction, offering a chance for a fresh start after a turbulent decade. Ultimately, much of the fragility of the past 10 years was tied to Türkiye’s Syrian story. As the new Syria steps into 2025, Türkiye, too, has ample reasons and opportunities for a fresh beginning. The key is for politics to recognize, by the end of 2024, that a new wave is inevitable globally and regionally and to step into 2025 accordingly.