The disarmament of the terrorist organization named PKK doesn’t mean that the Kurds are laying down their arms, but that they are laying down the sword of the Muslims’ enemy. Afterward, the Kurds will wield their own weapons, not those of Yorgo, and the gun barrels of those weapons will then point at their real enemies (the enemies of the Muslims), together with the Turks and Arabs. Only then will discussions about the Kurds and Kurdistan take place in an entirely different context. At this point, the possibility of any tyrannical, westernized minority rule existing after Syria revolution—or the survival of any Zionist state after Gaza resistance—is no longer feasible. Step by step, we will reclaim everything we lost a century ago, healing our wounds as we move forward. The effort to grasp this future truth transcends all theories, ideologies and policies.

We took a taxi on a foggy morning in London. By coincidence, the driver turned out to be from Urfa. He had been in London for 10 years; he and his family had settled there. For a while, he had worked as a private chauffeur. Later, he took the exams to drive one of the iconic black cabs and passed all the exams. They were extremely difficult tests; you had to memorize the entirety of London like a living navigation system. The road was long, there was traffic and we were listening to our driver from Urfa who was in love with his job. At one point, he asked, “Brother, what’s going on in Türkiye? I haven’t been keeping up. Yesterday, one of my passengers scolded me.” This was during the “peace process” or “resolution process” in Türkiye. “What scolding? What does it have to do with Türkiye?” we asked. Then, he began to explain: “I have a wealthy Greek client who I have been picking up from his home and taking to his workplace every day for several years. He likes me a lot, and I call him Uncle Yorgo. He’s a really kind man. We would chat every morning. Yesterday, he seemed a bit tense. He came in, holding the newspapers he gets every morning, and sat down. He was flipping through the papers. There was traffic again, he wasn’t talking much, then suddenly he rolled up the newspapers in his hand and started hitting the window between us, ‘What are you doing?, Who did you ask?, How can you lay down your guns?’ He was hitting the glass and shouting angrily. I didn’t understand what was going on. I asked, ‘Uncle Yorgo, what’s wrong? Did I do something wrong?’ He replied angrily, ‘What more?’ He said angrily, ‘You are laying down your weapons, we gave you these weapons, how can you leave them without asking us?’ ‘Whose gun are you twerp giving up?’ he said. I still didn’t understand. That gentleman uncle never spoke such slang. I asked, ‘What weapons, Uncle? Who’s laying down what to where?’ He opened one of the newspapers and showed me a news story. It was about a resolution agreement with the PKK, disarmament, and a statement from Apo (Abdullah Öcalan). It turned out Uncle Yorgo was talking about this. These were political matters I didn’t follow, so I really didn’t know anything about it. When the traffic slowed down, I turned to him and said, ‘Uncle, honestly, I have nothing to do with these issues. I’m just trying to make a living. Why are you mad at me?’ He yelled back angrily, ‘What do you mean you have nothing to do with it? Aren’t you a Kurd? I chose you because you’re Kurdish! We’ve supported you for years, and now you’ve gone and sold us out to the Turks. Don’t come to me anymore. I’ll find another driver!’ He didn’t say another word until we arrived at his workplace, and then he paid without even saying goodbye and stormed off angrily.” Our driver then said, “Brother, I don’t get it. What’s going on with these Greeks? I didn’t even know they loved the Kurds this much.” Our native of Urfa was really quite naive, or rather, he was a pure-hearted Anatolian boy. All that remained from the reproach he received from his uncle Yorgo was the sadness of losing a good customer.

Uncle Yorgo’s reaction reminded me of a conversation I had with an Armenian man of similar age in Armenia. He was painting and selling artworks at a market in Yerevan. He was the only child of a family from Van that had migrated to Yerevan. When Uncle Kevork learned that we were from Türkiye, he showed special interest, called his children and introduced them, told us about old times, and then invited us to his home. His wife, who was from Yozgat, made us delicious Yozgat-style dishes. They were a quintessential Anatolian family, and we forgot that we were in Yerevan. In Kevork’s library, I noticed some books by Abdullah Öcalan. To tease him, I said, “Uncle, I see you’re reading books by a Kurd.” He laughed and replied, “I was curious about what he was saying, what he was advocating for.” Then he added, “He added our people to the organization, let’s see where he takes them”, he said. I asked, “Who are your people?” He said naively, “Oh, our old villages.” “Some of them, at least. Occasionally, they get on buses and come to Yerevan to be baptized in church. They said ‘we are originally Armenian.’ Recently, our priests got upset and said, ‘You’re going to provoke Türkiye. Don’t come anymore.’ So, they’ve stopped. Now, Yazidis come here instead. They’ve settled in villages vacated by the Kurds. When they arrive, they say they’re Kurdish; here, when settled, they say they’re Yazidi.” Kevork kept telling us stories. At one point, Kevork said, “Come, I’ll show you Mount Ararat.” We all piled into his son’s car and headed toward Mount Ağrı. Everywhere in Yerevan—on monuments, large buildings, and even electricity poles—you could see the year “1915” written. While chatting along the way, I hesitantly asked Kevork, “Uncle, may I ask you something?” He replied, “Go ahead.” I said, “I see the year 1915 written everywhere. Türkiye started the Armenian initiative, Abdullah Gul came here, Erdogan said, ‘Our pain is common, let’s end this hostility.’ How will this issue of 1915 ever be resolved?” Kevork turned to look at the road for a long moment and then turned back to me. Slowly and emphatically, he recited Mehmet Emin Yurdakul’s poem, “Let Me Scream”.*

Then he turned away and remained silent. He didn’t speak until we reached our destination. I kept silent too. His son watched Mount Ararat and told about its place in Armenian mythology. The first generation of Noah to get off the ship were Armenians and Ararat was their sacred mountain. We did not discuss these issues until we returned back, with Uncle Kevork. But his son said, “This issue is an unhealable wound for our elderly people.”

I encountered another unhealed wound in Paris. As we were exiting a metro station, we spotted a restaurant with a sign that read “Istanbul Kebab” and decided to go in. When we said we were from Istanbul, both the owners and the waiters warmly welcomed us with big smiles and special attention. To their credit, the kebabs were delicious. After some chatting, we learned that the owners were a Chaldean family who had emigrated from Mardin. The waiters were Kurdish youths from Mardin, Diyarbakır, and Şırnak. They were incredibly helpful. One of the young men from Diyarbakır even got permission from his employer to act as a guide for us and took us to a few places. It seemed he had fled “the mountains” and found refuge here. He prayed regularly and was fasting that day for the soul of his mother. He spoke fondly of his employers, saying, “Most businesses here are owned by Armenians, Chaldeans, or Syriacs. They take care of us, give us jobs, and help with residence permits and other legal matters. The French treat Christians—Syriacs, Chaldeans, and Armenians—with special care and give them many opportunities.” The next day, we visited the restaurant again and spoke more with the owners. The youngest brother enthusiastically explained Chaldeanism to us. Occasionally, he’d throw in remarks like, “Kurds are barbarians, Turks are looters, and Arabs are desert monkeys,” only to backtrack and say, “But actually, we’re all Chaldeans, all descendants of the Prophet Abraham.” He grew even more excited and exclaimed, “Islam and Judaism will soon disappear, and everyone will become Chaldean!” Interrupting him, I asked, “Why don’t you like Turks, Kurds, or Arabs?” I had spoken without thinking. He began recounting a thousand years of history, passionately detailing how Arabs, Kurds, and Turks had massacred Chaldeans, Assyrians, Syriacs, and Yazidis for centuries, committing countless atrocities and genocides. It was as if he had memorized these grievances and recited them without pause. We listened patiently. Finally, he concluded, “That’s how it is, brother. Our wound is deep and will never heal.”

The wound truly was deep. Wherever we went, we encountered another deep wound. In Bulgaria, I came face to face with another one. Our guide there was a friend who had emigrated from Bulgaria. He told us his story: In 1988, the communist regime of Todor Zhivkov abruptly turned against Bulgaria’s Turkish minority. Turkish names were banned, and Turks were forced to adopt Bulgarian names. The Turkish minority, who had lived together until then and even had mixed marriages, were faced with the option of being exiled or taken to camps such as Belene without understanding what was happening. Our friend was one of the hundreds of thousands of Turks who had to migrate to Türkiye during this period. He was just a child then. “There was a Bulgarian family with whom we lived in the same apartment building. My mother was friends with the lady of the house and I was friends with her children. We had no problems. We were so close that we’d enter each other’s homes without hesitation. Even our fathers were close friends who had graduated from the same school. When Zhivkov’s policy began, we kids didn’t understand much, but the adults seemed uneasy. Still, life went on, and our neighbors continued living as usual. One evening, during dinner, the news announced that Turkish would no longer be allowed, and everyone had to take Bulgarian names. My parents were listening to the news in shock. A little while later, the doorbell rang. I ran to open it. It was our neighbor, Uncle Todor, holding a rifle—no exaggeration, an actual rifle! I said, ‘Come in, Uncle.’ But he sternly replied, ‘Go call your father, quickly.’ I’d never seen him like that before. Scared, I called my dad. When he saw Todor, my dad greeted him warmly as usual, saying, ‘Oh, neighbor, come on in!’ But Todor raised his rifle and pointed it at us, saying harshly, ‘I’m not coming in. Listen to me: follow Zhivkov’s orders. Remove your name from the doorbell immediately. Starting tomorrow, your entire family must change your names, or there will be consequences.’ Then, without waiting for a reply, he turned and went back to his apartment, slamming the door behind him. We were left standing at the door, stunned. Was this a joke? Was Uncle Todor mocking this absurd policy? My dad reassured us, saying it was just a joke. But in the days that followed, we realized it was no joke. Uncle Todor, our other Bulgarian neighbors, and even people in the neighborhood suddenly began treating us with hostility. The friendly relationships we’d built over the years vanished overnight. People started reporting usto the security units, threatening us, and cutting off contact. The number of hostile stares and gestures grew. I was a child and didn’t fully understand what was happening, but I’ll never forget the fear and confusion in the eyes of the adults. It was incomprehensible how neighbors, friends, and even relatives could turn so cold and hateful overnight. They kept saying, ‘We’re avenging the Ottomans.’ But we had forgotten about the Ottomans. That night, a wound opened in my heart that I’ll never forget…”

This is how my friend described it. They settled in Istanbul as a family, and our friend, due to this childhood trauma, gave the most importance to Turkish lessons at school and eventually chose the Turkish language and literature department as his university choice. After graduating, he served as a reserve officer during his military service in the 1990s, stationed in Şırnak. One day, while recounting his military memories, he leaned over and whispered, “We killed a lot of Kurds.” Shocked, I asked, “What do you mean? What are you talking about?” He replied, “I participated in many operations during my service. We killed Kurds and cut off their ears. Our commanders rewarded us.” Stunned, I said, “What are you saying? Killing Kurds? You mean PKK militants, don’t you?” He replied, “No, I know that region well—they’re all PKK. They don’t even speak Turkish.” I reminded him of his own story, saying, “Our state did the same thing as the Bulgarian state. It banned people from saying they’re Kurdish, from speaking their maternal language, Kurdish and that organization went to the mountains with this excuse, I said, don’t you know?” He dismissed it, saying, “It’s not related at all.” For him, speaking a language other than Turkish—or not learning Turkish—was a justifiable reason for killing someone. He had never empathized with the people he considered his enemies. For him, the best Kurd was a dead Kurd, and he refused to hear anything else. Even Bulgarians didn’t evoke as much hostility in him. He’d say, “I’m an Atatürkist, my friend. We won’t let anyone divide the homeland Atatürk entrusted to us.” He spoke of Atatürk as if he were a Balkan neighbor and saw the homeland as a private garden belonging only to those Balkan neighbors who had fought for it. He had no idea about Anatolia, the Middle East, the national struggle, or how the Republic of Türkiye was established—or rather, he had never questioned the narrative that had been instilled in him. He was unaware that he was trying to strangle and divide a country and nation that welcomed him with open arms while trying to protect them. Todor Zhivkov hadn’t just banned the use of Turkish—he had banned thinking like a Turk. To ban someone’s innate identity, let alone to even think about doing so, is something no Turk would ever imagine. In fact, this was something a retired Bulgarian police officer told us at a café in Bulgaria while our friend translated. The officer had been observing us from a nearby table and eventually asked, “Are you from Türkiye?” When we replied “yes”, he said, “I wish you Turks would come back here again. The Ottomans never interfered with our religion or language. Thanks to the Turks, we were able to preserve our identity for centuries. Then the Russians came, turned us into communists, and stripped us of our religion. Now the Europeans are wiping out all of our culture.” He sighed and added, “Our ancestors made a big mistake when they rebelled against the Ottomans and drove out the Turks.” Our Bulgarian immigrant friend translated his words with pride. I said to him, “See, this is what I’ve been trying to explain to you. Turkishness existed in history because it protected other identities and governed with justice. When they abandoned this purpose, no matter how much someone calls themselves a Turk, they fail to embody what it means to truly be one. Of course, he didn’t understand. The poison of Kemalism had dressed up “Turkishness” in a strange new costume—one that insisted on saying “I’m a Turk” but wouldn’t say “I’m a Muslim” or “I’m Ottoman.” It had fed the state with the policy of erasing those who didn’t conform to this artificial identity, presenting this as a matter of survival and national security. As a result, the very survival of the state was perpetually under threat.

I had the same fruitless argument with a PKK member I happened to meet and chat with in a Turkish café in Switzerland. What he said was just instead of saying “How happy is the one who says ‘I am a Turk”, he would say, “How happy is the one who says ‘I am a Kurd.'” What stood before me was the same alienation from one’s roots, the same artificial identity, and the same lack of awareness. The names of natural identities were reduced to idol concepts, and an ethnicist generation of ignorance that worshiped these words was created. “The occupier Republic of Türkiye had colonized Kurdistan for centuries, committed genocide against the Kurds, and the Kurds were defending their homeland against the occupiers. In all four parts of Kurdistan, a national liberation war would continue against the colonialist Turkish, Arab, and Persian imperialists until a united and great Kurdistan was established. The Kurds had been the rightful owners of Kurdistan since the Sumerians. There were 60 million stateless Kurds. For centuries, their rights had been usurped, and they had been oppressed, yet they had always been noble warriors who resisted with honor.” I listened patiently. It was an incredibly comfortable narrative, explaining everything in one sweep. It was like the pictures on the covers of Western magazines—handsome Kurdish youth and beautiful Kurdish girls in guerrilla uniforms, armed and posing like eagles of the mountains. It made you want to run to the mountains yourself. Like my Bulgarian immigrant friend, he also spoke of the Kurds as if they were the rightful owners of every place they lived. It was as if he were explaining how his siblings cheated him out of his inheritance while dividing up the Ottoman field. He had brought the conversation to this point, starting from the denial, assimilation, and oppression directed at the Kurds. I said, “Why don’t you take a ruler and measure out the Kurds’ shares? But keep in mind, don’t try to enter fields that don’t belong to you anymore. And if in the future, our children have to talk through a translator, you’re paying for the translation fees.” He hadn’t thought through the logical consequences of anything he defended. The last thing he had read were Stalin’s writings on “the right of nations to self-determination” and İsmail Beşikçi’s books.

As the conversation progressed, we delved into more mundane topics. He had obtained asylum in Switzerland because he was persecuted as a Kurd. In return, he sometimes helped the Swiss police, particularly in matters of controlling the drug mafia. When his lawsuits subsided, he invested in Türkiye. He had a summer house in Bodrum and would go there for vacations. He sent his children to private schools, which were very expensive. His wife spent a lot of money, and she wanted to vacation somewhere else this summer. His mother was very religious and would scold him every time she saw him for not praying and for drinking alcohol. Whenever he visited Türkiye, he would go to his village for nostalgia and was even considering building a house there. He complained that Europe had become unlivable, that his kids were addicted to video games and never put their phones down. When it came to the problems of normal life, he was quite rational. But when it came to the imaginary Kurdistan narrative, which had been produced and ingrained into him over decades from every direction, he became irrational and impossible to talk to. He was living in a fantasy world, building a state in his mind, running it with all its details—its history, culture, and politics—because he was chasing unattainable goals in the real world, and perhaps because he felt deep down that they would never be achieved. He would ask, “Everyone has a state, so why don’t we?” I said, “Türkiye is already a state for everyone. Some of us suffer from not having a place in history, while others suffer from having their place in history taken from them.” Of course, he didn’t understand.

It was as if he had created an artificial intelligence in his mind to simulate a Kurdistan and was discussing its relationships with Türkiye, Syria, Iraq, the West, Israel, and Iran. We had no common ground to talk about. This self-contained, self-validating tautological dilemma was something I once asked a former IRA leader in Ireland. “How did you break free from this tautology? How did you end a hundred years of resistance? What did you do with your guns?” I asked him. He was a friend of Bobby Sands, who died in the hunger strike resistance in prison in 1981, and he had also been part of the that resistance. He had participated in the negotiations with the British government and was now working on rehabilitating militants released from prison. “War is not the goal,” he said calmly. “War is a tool of politics. Weapons are taken up when there is no other choice. But when other ways open, weapons become an obstacle to solutions. That’s how it is if your aim is resolution.” Then he spoke about the experiences of the Sandinistas in Mexico, the ELN in Colombia, and ETA in Spain. Understanding why I had asked, he continued: “You need to resolve your Kurdish issue without weapons. Weapons not only poison those who hold them but also the next generations. We are still dealing with the consequences of this. Both your state and the organization must abandon nationalism. Freedom and democracy are stronger medicines for a society than nationalism. In such a climate, everything rigid will dissolve. Words are better tools for communication than the sounds of weapons.”

Even though it was hard for me to have to listen to these simple advices from an IRA militant, which is already in our core, I remembered my despair in Switzerland and thought that maybe these simple formulas could untie the hardened souls and the locked knots. Prohibition divides, freedom unites. But if you seize the state and attempt to create a new nation with francophone formulas handed to you, and then carefully strip it of Islam and history, imposing your own ethno-religious, converted lifestyle as the Turkish identity, this “shirt” will so tight. And people like us will end up producing the antithesis of this nonsense, trying to explain reasonable words to the remnants of racist ignorance it generates. Our lives have been spent with the tangle of problems that they bracketed and consumed.

Cemil Meriç came to mind. He once said:

“This country has been taking on water like a sinking ship since the French Revolution.”

He wrote:

“Whether you climb the mast or lie back on the railing of a sinking ship… This country has been taking on water like a sinking ship since 1789. What was destroyed in 1789 wasn’t just the aristocracies of the West or the feudal social order; it was the victory of the bourgeoisie and the death knell for the ancient East… The mighty Ottoman State, which had collected tribute from kings for centuries, no longer held the sword of conquest in its feeble hands—only the beggar’s bowl. People of different colors waiting impatiently for the day when they could claw at each other’s throats. And finally, dissolution. The Sick Man is still dying.

Ever since the patchwork of the empire’s hostile ethnic elements came apart at its seams, we have become a people hostile to ourselves. The past is gone; we don’t know our own history. Religion lies on its deathbed. No ideology has been born to unite people.”**

**(Cemil Meriç, Jurnal – Volume 1)

Cemil Meriç was right. In the end, nationalism, the nation-state, the “self-determination of nations” and similar jargon are products of the French Revolution. Their reflection on us resulted in the creation of small, ethnically and religiously fragmented statelets on the remains of the Ottoman field. The wounds of Yorgo, Todor, Kevork, and others, those whose wounds unhealed, were actually the result of their own betrayal, incited by the West. During the Crusades, and then in the final Crusade that led to the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, they welcomed the English, French, and Russians with flowers in their hands and weapons at their belts, only to open deep wounds in the hearts of the poor Muslim population that had never touched them for a thousand years. This wound was one we could never articulate as eloquently as they could.

Now again, this time the demand for a new squatter state at the expense of the Kurds, who are Muslims and a truly pure co-religionist-brother-comrade people, is still being provoked with an anti-Ottoman motivation. The pain suffered and the oppression committed as a result of the denialist policies of the Republic of Türkiye, which was carried out by performing eye surgery with an axe, in order to prevent a similar disintegration after the Ottoman Empire, are now legitimate reasons for establishing this squatter state, not for repentance or recanting from mistakes. However, any willpower that speaks on behalf of the Kurds, fights, and defends the rights of the Kurds with arms is not a formula that will, in the final analysis, truly ensure the historical existence of the Kurds in favor of the Kurds. On the contrary, such actions by alienating the Kurds forever from their brothers and sisters, will turn them into a minortiy as source of perpetual conflict like the Shia, Alevi, or Armenian identities in the region.

For this reason, the primary goal must always be to learn from the pains and conflicts of recent history, to avoid opening new unhealed wounds, and to heal the wounds that already exist. Those who want to include the Kurds in experiences like the Armenian tragedy, the Israeli project, and the Alawite minority dictatorship in Syria may perhaps be pleased, but the fact that every sentence constructed with the alienating, ghettoizing expressions that reduce Kurds to the level of a nearly homogeneous tribe-organization name should terrify everyone, because this stance will rather than bringing Kurds into history, such rhetoric risks making them the next victims of the Middle East.

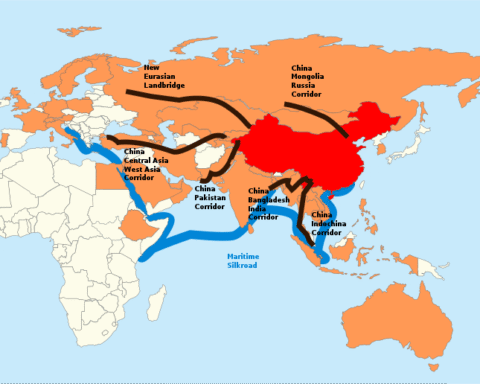

The organization called the PKK—whether it was the hidden hand at its birth, the later Syria-Iran-Russia-France organization, or today’s U.S.-UK-Israel-sponsored narco-terror network, or even the Kurdish people’s will to protect themselves and achieve their demands through resistance—must, in every sense, reach its conclusion, step down from the backs of the Kurds, and set Kurdish society free. It can do this by celebrating the victory of achieving its goal through armed struggle, or as a stage of not fully achieving it and continuing unarmed. In any case, it must first get off the backs of the Kurds, abandon its monopoly of speaking on behalf of the Kurds, and instead of negotiating between capitals in this tribal lord manner, it must pave the way for the Kurdish people to exist in individual, social group diversity and harmony, just like all other normal peoples.

It is more reasonable to focus on developing a new perspective and conceptual paradigm that will redirect all the motivational energy of the Kurdish people, which has so far been wasted or turned into being pawns of foreign powers for an imaginary process of nation-building, into reformatting Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Caucasian and Balkan peoples not as separate ethnic tribes but as a single and pluralistic nation, transforming them into a founding dynamic of a history in which the Middle East, Eurasia, Africa, and Europe are being reshaped.

Yes, Türkiye may have made grave mistakes in the name of survival, born from the necessity of its existence on the corpse of the Ottoman Empire. But in the final analysis, its experiments with democracy, its modernization while retaining its Islamic character, and its ability to transition through periods of tutelage and civil conflict toward democracy without bloodshed, still stand as an exemplary model for all Muslim societies. It is possible to deepen, improve, and advance this experience. This is what politics is for—a means to solve problems without weapons, fights, or bloodshed.

Sometimes, people and societies only understand the value of something after they’ve lost it. Those who fail to recognize that Türkiye, and all the historical dynamics that created it—including the Kurds—are part of a deep shared history and mutual survival, are essentially digging their own graves when they turn to the West or East for mandates.

We don’t know if the PKK will be able to simultaneously abandon all the weapons—both literal and ideological—that have been forced into its hands and mind for the past 40 years. It has a bloody history of setting out to take revenge for 1915, 1922, 1925, 1937, the exiles, Diyarbakır Prison, the emptied villages, the forced ingestion of feces, the cutting off of ears but this “struggle” concluded by passing through bloody path in which it is still killing the children of Anatolia, murdering those who are not like themselves, bombing civilians, and executing thousands of Kurds within its own ranks, burying them in unmarked graves. The PKK is an organization that started in the late 1970s in Damascus under the patronage of Rifaat al-Assad, Russian officers, and French advisors and later continued with the support of Britain, Iran, the U.S., and Israel, and even established proxy hostility alliances with Greece, Armenians, Serbs, Chaldeans, Assyrians, and anyone who had an problem with Türkiye. The organization has deviated from its original path and has become captive to these relationships. Convincing such an organization that the game is over is extremely difficult—but not impossible. Because the majority of the Kurdish people now await, with a calm and quiet hope, to be freed from the guardianship of a senseless and blinded organization. It is a hopeful wait that this time, the hand of sincere brotherhood extended by the state will not be bitten. “Perhaps a film will come to the city, and a beautiful forest will grow.”

The most important duty is to protect our children from those who want to make sure this dirty game, this dirty war continue, from those who incite Anatolian children from the comfort of their lives in Europe or other countries under the guise of Kurdish nationalism, from those jobbers who have poisoned our children with countless snakes, scorpions, and devils to make profit from the counter side under the pretense of combating terrorism, securing a place of legitimacy within the state, and deluding themselves into thinking they are promoting Turkish nationalism through Kurdish hostility and from the evil of secular racist identity politics that has replaced natural Turkishness and natural Kurdishness.

Whoever achieves this, in whatever way, will be a true patriot and nation-builder who makes history. Whoever obstructs or sabotages this will be remembered in history as an eternal enemy of this country and its people.

Only then, in order to heal the unhealed wounds of millions of Muslims who were massacred in the Balkans, Caucasus, Tripolice, martyred in Sarıkamış, Çanakkale, Kutul Amare in the Sinai desert; and to take revenge for the millions of Muslims murdered in Iraq, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Kashmir, Sudan, Yemen, Palestine, Syria and Gaza, that is, to see our own unfinished accounts, we open the ledgers and for the first time instead of wars exposed by the outsiders we start our own wars. Because there is no one else who mourns the lives, blood, and shattered bodies of Muslim children. There is no one else who feels the pain, no one else who sheds tears. We have no choice but to make our our own wounds our cause .

We have much work to do. The old eras and the old games are over. The Turkish, Kurdish, and Arab Muslims must no longer be the pawns of Wilson, Stalin, Churchill, or the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Instead, they must take up the watch of Saladin, Andalusia, Baybars, Sultan Selim the Just, and Idris-i Bitlisi.

The disarmament of the terrorist organization named PKK doesn’t mean that the Kurds are laying down their arms, but that they are laying down the sword of the Muslims’ enemy. Afterward, the Kurds will wield their own weapons, not those of Yorgo, and the gun barrels of those weapons will then point at their real enemies (the enemies of the Muslims), together with the Turks and Arabs. Only then will discussions about the Kurds and Kurdistan take place in an entirely different context. At this point, the possibility of any tyrannical, westernized minority rule existing after Syria revolution—or the survival of any Zionist state after Gaza resistance—is no longer feasible. Step by step, we will reclaim everything we lost a century ago, healing our wounds as we move forward. The effort to grasp this future truth transcends all theories, ideologies and policies.

The honor of the Kurd is tied to the pride of the Turk; the Turk’s fear of division is tied to the Kurd’s dignity. Whoever inserts “and,” “a comma,” or “a period” between brothers and sisters with ethnicist, racist, or nationalist intentions—whether Turkish or Kurdish—is an enemy of us all.

It is now time to shout out the words of Mehmet Emin Yurdakul’s poem:

*”I am the soul that counts the most deprostrate person as my brother;

I believe in a God who does not create bondslaves.

The poor wrapped in rags wound me deeply;

I was born to be the vengeance of the oppressed.

The volcano may die, but my flames will never diminish;

The storm may pass, but my waves will never cease.

Let me cry out; if I fall silent, you must mourn;

Remember that a nation whose poets do not cry out,

Is like an orphaned child whose loved ones lie in the soil.

Time shows him its teeth dripping with blood,

For such wretched people, there is neither mercy nor justice;

Only a stern, sharp-eyed gaze and a heavy fist!”

*(Mehmet Emin Yurdakul, “Let Me Cry Out”)

Tercüme: Ali Karakuş