“Hide your strength; bide your time.” For over two decades, starting in 1992, this famousquote attributed to Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s reform movement, served as a sacred verse, guiding China in shaping its Middle East policy. This phrase encapsulatedChina’s masterclass approach of “Strategic Ambiguity” and patience in this region. Thispolicy remained in place until Xi Jinping came to power in 2013. Under Xi, China wastransitioning from a Rule-Taker to a Rule-Maker. This time, he was determined to “tellChina’s story well” in his own words. The cautious tightrope walker, careful to avoid theslightest slip in his steps on the tightrope, now wanted to delight the audience with his acrobatic moves. This evolution required a change in China’s mode of action from absolutenon-involvement in the region to selective involvement, which meant appearing as a cautious, selective mediator in cases where its intervention was likely to be constructive—the time had come to move from China’s long-term hedging policy to a more assertive wedging policy. However, the region’s rapid and highly unpredictable changes since October 7, 2023, have ledeven Xi Jinping’s China to return to its traditional cautious approach. Is China once againshifting from a true mediator to a silent architect? Why has China’s strategy in the MiddleEast been in flux recently?

In the 1950s and 1960s, China sought to create anti-colonial sentiment among Middle Easterncountries and gain political support to check Soviet and Western influence in the region. In1978, with the start of Deng Xiaoping’s economic modernization policy, China reduced the importance of its political and ideological goals in favor of financial interests and made a complete shift in the priority of its regional goals. This led to normalizing relations betweenChina and all Middle Eastern countries. From this time, China turned to a hedging policy, avoiding taking sides in favor of either side in ethnic and geopolitical conflicts between each of these countries. It adopted a balanced and neutral approach with all regional powers while being prudent not to harm or confront the U.S. as the dominant trans-regional power. It also changed its policy towards the Arab-Israeli conflict. While supporting the formation of an independent Palestinian state, it turned to establishing economic relations with Israel and using the country’s advanced technology in agriculture based on an economically oriented foreign policy. In January 1992, China officially established diplomatic relations with Israel. China faithfully adhered to the policy of hedging, maintaining neutrality, and staying out of conflicts throughout the 2000s. Before Xi came to power, walking carefully on the tightropewas more critical to the tightrope walker than the conspicuous nature of the tightrope walk.

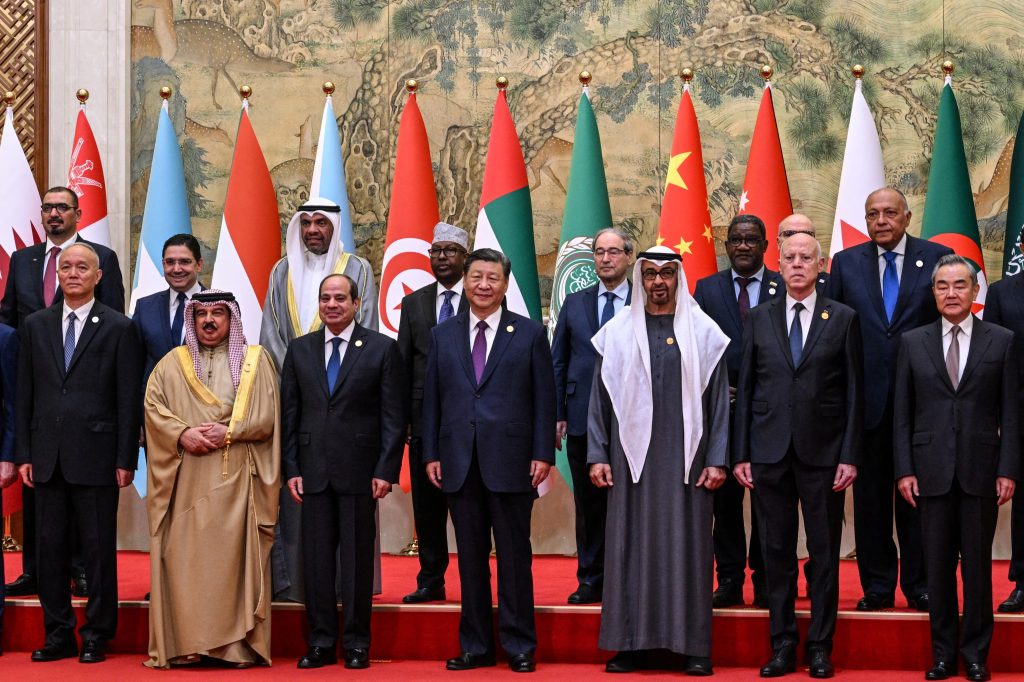

With Xi coming to power in 2013, China’s foreign policy approach underwent a fundamental shift, influenced by Xi’s ambitions. “The Chinese people have long been the masters of theirdestiny and will never allow anyone to bully, oppress, or subjugate us.” He was determined not to allow China to be humiliated by any foreign power and, from now on, to move frommerely accepting the existing international order to changing it to maximize China’s benefits from it. One of Xi’s primary goals in his new “Wedging Policy” was to undermine the U.S. leadership style worldwide, including in the Middle East. Accordingly, Xi took initiatives in various fields to present alternative models for development and security and sought to createinternational institutions that rival existing institutions created based on U.S. preferences. He also emphasized the indigenous values of each country instead of universal values dictated bythe West. One of China’s levers of influence in the Middle East was its increasing involvement as a mediator and peacemaker among conflicting regional powers. Of course, China has limited this mediation to cases where its geostrategic and economic interests wereat great risk. One significant example was the mediation between Iran and Saudi Arabia, where China had extensive financial ties with both sides of the conflict. In this case, China believed in the constructiveness of its role in this reconciliation to position itself as a regional power broker. China could use this leverage within the framework of the wedge-jumping policy to drive a wedge between the U.S. and its regional ally, Saudi Arabia. The cautious former tightrope walker, led by his new leader’s bold policy in recent years, has tried his luckat performing an eye-catching acrobatic move, an experience that has been a success.

Though events after October 7, 2023, showed that it is too early to call China the superpowerin times of crisis, while its presence is undeniable, it has yet to unleash its full force of influence. China strikes a delicate balance between assertiveness and restraints in criticalmoments. However, it is essential to recognize that, under Xi’s leadership, this time, “Re-hedging” also carried underlying motives rooted in wedging. The Gaza crisis gave China a rare opportunity to project its idea of presenting itself as a model for the developing world and the image of a superpower that does not act biasedly or unilaterally in regional conflicts, particularly in the eyes of the Arab world. For years, the U.S. has blamed China for taking advantage of America’s presence in the Middle East without contributing. China’s turn was tourge the U.S. to reassess its track record in the region– a legacy filled with missteps and partiality. Perhaps prolonging would also help tarnish the U.S. image among people of theMiddle East and would have served China’s medium- and long-term interests.

Additionally, the war forced the U.S. to temporarily divert its attention from East Asia, refocusing on the Middle East. This shift aligned with China’s broader interests in the ongoing competition between the two superpowers. On the other hand, China’s improbabilityin effectively mediating this crisis would make it reluctant to undertake a similar role as a mediator between Iran and Saudi Arabia. The direct involvement of the U.S. in the conflict in favor of Israel and the daily changing nature of the war’s dimensions made it difficult forChina to mediate on the principle of neutrality.

While China under Xi was practicing how to implement a policy of wedging in the MiddleEast, the highly fluid and unpredictable developments of the Gaza crisis forced the country to return to its traditional hedging policy, albeit with a different nature, aimed at gaining popularity among the Arab public opinion and creating a rift between the U.S. and its regional allies. The Israel-Palestine was a complex and polarizing issue; Xi was shrewdly cautious about conducting himself in this crisis in a way that would not cause serious friction in his relations with any pillars of power in the region, including Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Israel on cethe crisis was over. Unlike the Iran-Saudi conflict, which was a vital issue for China in terms of securing its energy imports, the Palestinian-Israel conflict did not directly threaten China’s interests.

Xi preferred a functioning role in the quiet and discreet architecture of the Middle East after the Gaza crisis, observing the changing balance of power among regional powers rather than having an active presence to resolve the situation. Hence, this tightrope walker chose to gingerly balance its economic ties with Israel and its moral standing in the Arab world, knowing that the slightest misstep could send its delicate geopolitical position tumbling.

* Dr Sika Sadoddin is a specialist in Middle Eastern Studies with a PhD from the Universityof Tehran. She lectured at various universities, including Tehran University, Shahid BeheshtiUniversity, and Qom University. She also served as a researcher at Portland State Universityin the US. Her research interests primarily focus on China’s policy in the Middle East and itsrelationships with key regional powers.