For a long time, the words archeology and religion were thought of as concepts that were not possible to come together. Archaeology, asserting itself as a modern science, was more closely associated with the natural sciences. In fact, it could be said that from beginning of the 19th century, when archaeology began to take shape as a result of Westerners’ curiosity about antiquities and the origins of civilization, until the 1950s, archaeology had remained an area focused on classifying and describing remains of the past and bringing them to prestigious museums. Archaeology, which promises to illuminate our distant past through material culture, has ignored certain aspects of human life that is complex and multidimensional regardless of time. This perspective built a wall between modern humans and those coded as “primitive” from earlier periods, assuming an evolutionary, linear, and progressive view of history that positioned Westerners as the pinnacle of human development. Through a fragmented and selective perspective, world history was constructed, and subjects such as religion and art were thus left outside the scope of archaeology. Religion, thought to pertain more to abstract and intellectual realms, was generally excluded from archaeological research. This was based on the idea that religion could not be understood through material culture and that archaeology could only provide information about daily life and, to some extent, issues like family, society, and hierarchy. In this period of archaeological studies, religion was either not included at all, or, if it was partially addressed, it was presented as a deviation in human history, an illusion of people who had not completed their evolution, or as an impediment to progress.

It should be noted here that Holy Land Archeology, or Biblical Archeology as it is commonly known, has survived to a large extent outside of these discussions. In fact, the story of the emergence of archeology has a direct relationship with the discovery of the twin origins of the West. The first of these roots was religion, which began with geological research sparking debates about the age of the Earth and thus raising doubts about the information given in the Bible. Consequently, researchers who sought to disprove the Bible found themselves opposed by others researchers armed with a trowel and the Bible. The other root focused on determining the origins of civilization and tracing the route through which it reached Europe. Thus, numerous excavations were conducted in places such as Palestine, Syria, Egypt, and Iraq to reveal sites mentioned in the Bible and to trace the transmission of civilization to Europe.

The social, political, and economic conditions following World War II also affected archaeology. As a result, the previous approach gave way to Processual Archaeology, which emerged in North America under the leadership of Lewis Binford (1931–2011). This approach, which views the past as a system, recognized religion as part of ideology and included it as a component of the past. Consequently, since the 1960s, it has begun to be said that religion can also be included in the field of archeology. However, it should be noted that in this approach, an understanding of religion confined to cemeteries, temples and shrines has been the subject of research. The Greco-Roman and Christian worldview has a significant impact on the background of confining religion to a narrow area. According to this worldview, the sacred and “secular” were sharply separated, thus isolating religion from what was considered normal and casual. This tendency of the West to center its own experience in reading and reconstructing the past has led to serious problems.

Postmodern debates have also influenced archaeology, giving rise to the Post-Processual Archaeology movement under the leadership of thinkers like Ian Hodder. According to this approach, interpretation has come to the fore in archeology, and material culture has begun to be presented within the framework of “context” and within a systematic. This situation brought forward the notion that there could be an archaeology of everything. As a result, discussions have begun within the framework of the concept of religion archeology, especially since the 1990s.

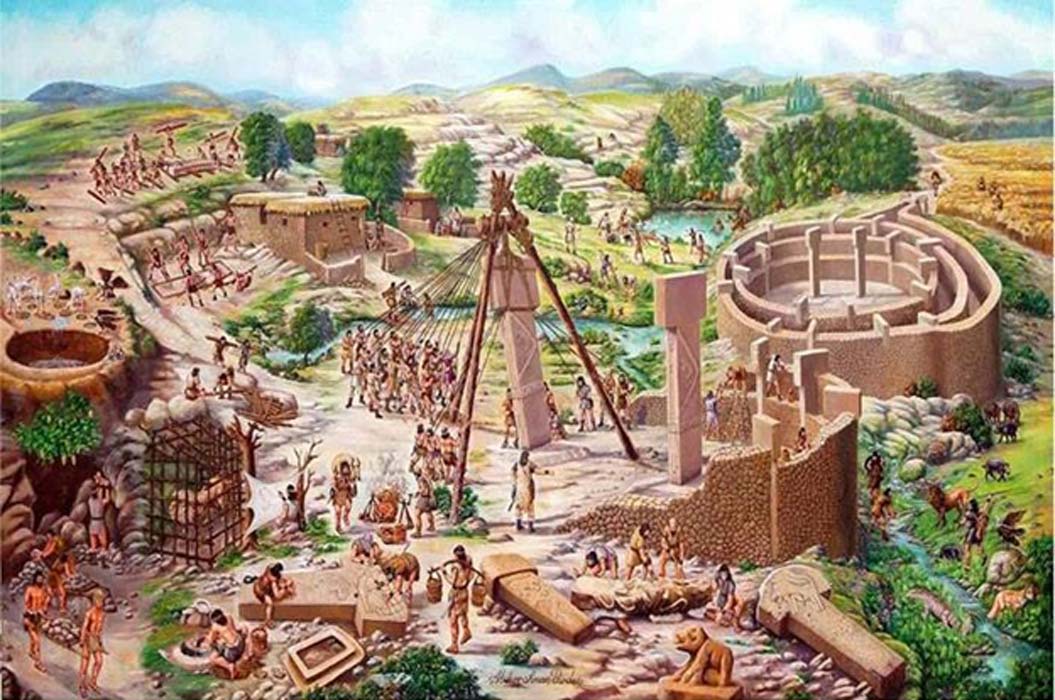

In the history of archaeological thought, it was a dominant belief that religion emerged after the discovery of agriculture in the Neolithic period. Accordingly, people who were constantly on the move in the pre-agricultural period did not have time to deal with areas such as religion and belief because they were struggling to survive. With the agricultural revolution, surplus products emerged, allowing some members of society to specialize in areas like the religion, the arts and crafts while others focused on meeting the need of foods, leading to the development of institutionalized religions. However, archaeological sites such as Göbekli Tepe have invalidated these paradigms. The Stone Hills, including Göbekli Tepe, which date back to before the generally accepted period of the discovery of agriculture, have shown that humans have had a rich world of meaning and understanding of religion since early times. In fact, paintings found in Altamira and Chauvet caves during the Paleolithic era, the earliest accepted stage of humanity, suggest that the history of religion extends much further back. Thus, it reveals that religion has been present since the much more early stages of history, leave aside the transition to a settled life.

This reality points to the impossibility and meaninglessness of determining the origin of religion or the precise moment it emerged from the perspective of religions history. Religion has existed alongside conscious human beings and continues to exert its influence on individuals and societies today. As a matter of fact, in this regard, secularization theories, which predict that religion is an illusion belonging to the pre-modern period of humanity and will end, have lost their importance.

Moreover, certain characteristics of today’s widespread world religions undoubtedly contribute significantly to understanding past beliefs. For example, recent studies on Islamic archeology have shown that, contrary to popular belief, religion in the case of Islam cannot be confined to a certain area and that it affects and shapes many aspects of life. Thus, it has been demonstrated that religion’s traces can be followed through material culture in many areas, from daily life to war, trade, and architecture. In this regard, as noted by researchers such as Timothy Insoll, who work in the field of the archaeology of religions, it is possible to develop more accurate interpretations of past beliefs by taking into account the distinctive approach of Islam.

The relationship to be established between the history of religions and archaeology will enable archaeologists to interpret material culture from a broader perspective. There are many common concepts and the subjects shaped by these two disciplines. Concepts and issues that have largely been clarified or that only point to a specific historical period in the field of religions history continue to be discussed from an archaeological perspective. In this regard, the history of religions can play an important role in understanding many concepts with problematic meanings inherited from the 19th century, such as primitive, Shamanism and ritual.

Contact with archeology will open the door to a new world for the discipline of History of Religions also. The study of religions history primarily begins with the religions of Mesopotamia and Hinduism to explore humanity’s religious experience. Yet, during the period known as prehistory, there were numerous beliefs and religious practices. Although these prehistoric beliefs were widely discussed in the early days of modern religions history, Max Müller’s comparative philology was later taken to the center. Consequently, material culture was practically excluded as a source, and the beliefs of the period called pre-writing were left to archaeologists and anthropologists. As a result of contact with archaeology, these beliefs will gain a new dimension by being interpreted with the rich knowledge of the history of religions. Thus, the archaeology of religion is emerging as an interdisciplinary field. Let’s finish the last word by directly answering the question in the title of the article: a relationship between archaeology and the history of religions can be established. In fact, it can be argued that without this relationship, a proper understanding of the past and therefore, the building of the future on solid foundations will not be possible.