What has been unfolding on the Syrian front in recent days is not merely a matter of military activity or a temporary tactical maneuver. On the contrary, we are standing at a threshold where long-standing structural problems, suppressed social unrest, and unsustainable political choices have become visible. The position of the SDF, the PKK’s ideological and organizational influence over this structure, the growing discontent of Arab tribes, and the Damascus regime’s recentralization efforts constitute the key components of this threshold.

Accurately reading this picture is of critical importance—not only for the future of Syria, but also for addressing Türkiye’s security concerns, bringing the Kurdish issue into the political domain, enabling an open discussion of the state’s democratic transformation, and ensuring regional stability. Thus, what we are dealing with today is not merely a question of what each side demands, but rather the need to precisely identify the point at which the politics of arms has caused paralysis—and how that paralysis can be overcome. At this stage, it is plainly clear that the insistence on constructing politics through armed presence serves no meaningful purpose.

SDF: From a Military Structure to a Political Burden

From the very beginning, the SDF was presented as a product of military necessity. Having received international support in the context of the fight against ISIS, the structure gradually moved beyond its military framework and took on a political, ideological, and administrative character. This is precisely where the problem began. There has never been a true overlap between the PKK’s ideological orientation and organizational baggage and the SDF’s claim of being a multi-identity, local security structure. The consequences of this insistence were most acutely felt in Arab regions. In areas with a significant Arab population, the SDF was not regarded as a “local defense force” but rather as an externally imposed project—one lacking any ideological, cultural, political, or religious ties to the local population.

At times, this reality manifested itself through armed resistance. Practices such as forced conscription, child abduction, the bypassing of local decision-making mechanisms, the disregard of tribal hierarchies, the monopolization of all decisions by the organization, and the imposition of a uniform political discourse only served to deepen the existing discontent. The maximalist demands that surfaced after the fall of the Assad regime, the insistence on positions incompatible with sociology and demographics, the desire to use weapons as a tool of coercion, and the attempts to exploit Ankara’s sensitivity amid the ongoing process failed to yield any gains for the SDF. On the contrary, at this point, while struggling to maintain its military presence, the SDF has largely lost both its maneuvering space on the ground and its political legitimacy.

The Arab Tribes’ Objection: A Suppressed Social Reality

It would be a grave mistake to interpret the recent reactions from Arab tribes as spontaneous eruptions or externally orchestrated moves. These objections are the long-overdue expression of a deep and long-ignored social discomfort—an expected but delayed sociological stance. What is happening on the ground also reveals that this suppressed unrest has now reached an unmanageable point. For Arab tribes, the issue is not about living alongside the Kurds or keeping their distance from the central government. The real problem is that they are unable to speak for themselves in their own lands, as local balances and social relations have been confined within an ideological framework. Under the PKK’s influence, the SDF’s gradual transformation into an ideological instrument has pushed local actors out of the political sphere and deepened the crisis of representation.

Therefore, the tribes’ tendency to reestablish relations with the Damascus administration should not be viewed merely as a reaction, but also as a deliberate political stance. Interpreting this choice solely as a “rapprochement with the regime” is both incomplete and misleading. What we are actually witnessing is a situation in which the relative predictability offered by the central state is perceived as a safer ground than the ideological ambiguity and arbitrariness of armed structures.

At this point, another critical reality that must not be overlooked is the position of Kurdish civilians. Neither the SDF nor the PKK represents the entirety of the Kurdish population. On the contrary, as in all cases where armed presence determines the political landscape, the pressure imposed by these structures has most severely restricted the Kurds’ own political space. The inability to develop local will, civil politics, and pluralistic representation is a fundamental problem that the Kurds themselves have long faced. Every structure shaped under the shadow of arms silences not only its opponents but also the very society it claims to represent. Accordingly, the current disintegration in Syria is not only the outcome of the suppression of Arab tribes’ political demands, but also of those of Kurdish civilians.

In this context, the decree issued by the Damascus government on January 16, 2026, concerning the cultural and political rights of the Kurds, is an important indication that a basis for engagement outside of armed structures is indeed possible. Naturally, the real meaning of this document will be determined by how it is implemented both on the ground and in the political sphere. Nonetheless, this step is significant in that it signals the existence of a space where politics—not weapons—can become the medium of dialogue.

Kandil’s Pressure and Maximalist Demands

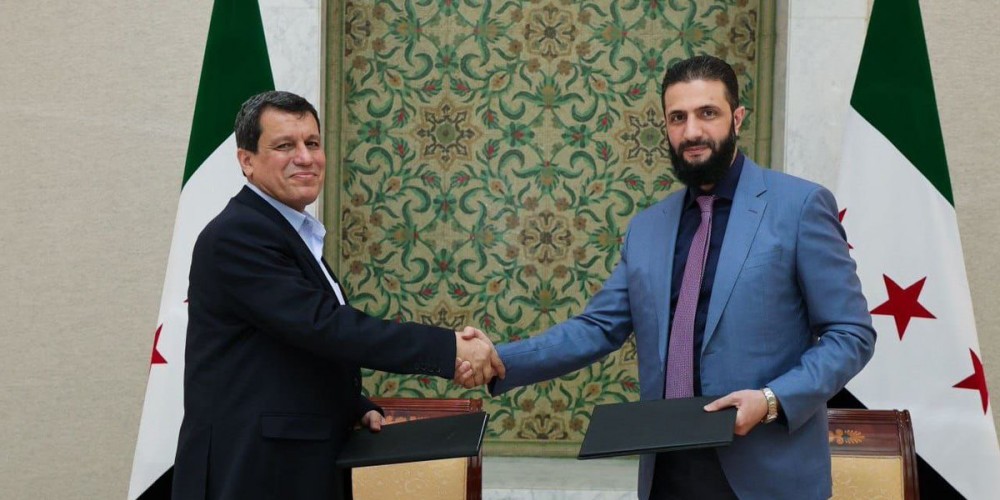

The ongoing disintegration on the ground has further hardened the stance of the PKK cadres based in Kandil. As territorial losses mounted, the organizational and ideological pressure placed on the SDF intensified. Maximalist demands and “time-buying” strategies became the central instruments of this increasingly rigid posture. This was made particularly clear during and after the Shara–Abdi meeting held in Damascus on January 19.

Yet at the heart of this situation lies a profound contradiction: while the reality on the ground points to an ever-narrowing military and social space, the expansion of demands reflects a politically untenable insistence.

This approach not only fails to improve the SDF’s operational flexibility on the ground, but also renders it more vulnerable—both in the eyes of Damascus and among its own social base. Needless to say, the effort to buy time does not yield any form of strategic depth. On the contrary, it merely postpones an unavoidable reckoning and raises the overall cost. The resulting picture further undermines the SDF’s capacity to make autonomous decisions about its own future.

Centralization, Security, and Politics

From the standpoint of the Damascus administration, recent developments offer a significant window of opportunity. Yet this opportunity will only carry meaning if it goes beyond merely reestablishing military control. Enduring normalization requires the formulation of a political discourse that is inclusive rather than coercive—one that respects local sensitivities, acknowledges identities, makes room for them, and fosters direct engagement with tribal structures. Otherwise, the reactions currently directed at the SDF may well reemerge in other forms down the line.

This broader picture also marks a similar threshold for Türkiye. The ongoing process is meaningful not only in terms of border security but also in laying the groundwork for the PKK to disarm and for the political space to expand. The narrowing of the PKK’s maneuvering room in Syria further weakens the justification for armed struggle within Türkiye. Still, this alone does not amount to a solution. Security gains can only be made lasting through the application of political foresight. Once again, the developments in Syria underscore the enduring nature of politics—not weapons. In short, neither Damascus’s centralization initiative nor Ankara’s security gains can achieve permanence unless they are reinforced by political action.

Rationality Is a Necessity

At this stage, there exists a common and indisputable truth for all: maximalist ambitions, ideological intransigence, and projects that disregard social reality are unsustainable. Neither the continuation of the SDF in its current form, nor the PKK’s attempts to achieve strategic gains through this structure, nor the region’s tolerance for new conflicts can be sustained. Rationality is no longer a matter of preference—it is a necessity.

The future of Syria depends on a political order cleansed of armed structures; the future of the Kurdish issue depends on a political discourse entirely severed from violence. For both organizations and states, the primary objective must be democratic transformation. What truly matters is not to endlessly repeat the term, but to give it concrete expression across all areas of life and politics. Those who fail to recognize this truth today may have to face far more severe consequences tomorrow.