A year has passed since the Syrian revolution, and during this time—despite sanctions and Israel—much greater ground has been covered than anyone could have expected. Sanctions were lifted, Damascus became a regional center of visitation, and in the Middle East, a free Syrian state emerged—one where people respect their state not out of fear, but of their own free will.

A year has passed…

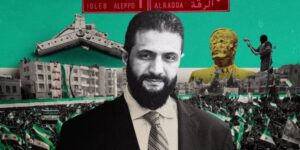

President Ahmed al-Shara appeared before the public wearing the clothes of Abu Muhammad al-Julani, which he had worn during the “Deterrence of Aggression” War. Accompanied by light security, he passed through thousands of Syrian citizens who had gathered entirely of their own accord, without any security checks or inspections, and made his way to the Umayyad Mosque. He climbed the pulpit and said: “You are the reason for our success; we will continue on our path with your support.” This was a scene rarely witnessed in any other Arab country, and words no Arab leader would easily utter.

Ahmed al-Shara had chosen his attire for the day with great care. He was sending a clear message to those around him: he was still the same person—unchanged. Standing on the pulpit of the Umayyad Mosque, addressing the young men who had been on the front lines during the entry into Damascus—none of them older than twenty—he emphasized that he was still Abu Muhammad al-Julani, their sheikh and devout commander in the battles of northern Syria. He demonstrated that the realism of politics had not, at its core, changed all that much.

His message to the outside world was this: “We have not taken off our battle uniform, and we continue to take pride in our history of struggle, in which we did not kill a single innocent person, but rather put ourselves in danger to protect civilians.” In fact, just a few days earlier, he had spoken these same words at the Doha Forum, in front of a Western anchor who had assumed he would use expressions that distanced himself from his past.

This morning, takbirs rose from all the minarets of Syria. This was not merely a celebration of victory; it was the reinforcement of the identity of that victory. Then, military parades began throughout Syria. The most provocative scene for Israel was the flyover of “Shahin” drones in the southern city of Deraa. In southern Syria, which Netanyahu repeatedly claimed he would disarm—in Deraa, the city where the revolution began—Israel’s advance was halted, it was met with confrontation, and the city gave its sons as martyrs.

This year has been long and difficult. This state, still in its birth phase, has faced crises and challenges that could shake even larger and more stable nations. In the earliest hours of the revolution, some regional countries attempted to claim victory by sending militant groups from the south toward Damascus. However, the speed of Ahmed al-Shara and his comrades’ advance was faster than the pace of decision-making at conference tables; their arrival in Damascus was even quicker than the duration of the meetings being held at the time. In the middle of a political minefield, with Türkiye’s diplomatic support, Syria first convinced regional countries that the new administration was rational and sensible, and then a diplomatic support alliance was formed consisting of Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, and Qatar. Within the first year, al-Shara appeared in the same frame as Trump and Putin, while other functional states were willing to endure humiliation and belittlement just to have their picture taken with the U.S. Secretary of State.

Al-Shara also introduced a new political slogan in response to those who accused him of being pragmatic. He said: “Pragmatism is a negative concept; it creates the perception that a person is faced with two options—one correct and one pragmatic—and chooses the pragmatic one. But this is called practical politics; we simply see the steps that need to be taken and implement them.”

A year has passed since the Syrian revolution, and during this time—despite sanctions and Israel—much greater ground has been covered than could have been imagined. Sanctions were lifted, Damascus became a regional center of visitation, and in the Middle East, a free Syrian state emerged—one where people respect their government not out of fear, but of their own free will.