When trying to understand world politics, we often come across the same sentence in many countries: “The US and the West control everything.” Sometimes we hear this phrase in street conversations, sometimes in university debates, and sometimes in politicians’ statements. Many groups, including intellectual circles, resort to this simplifying framework, especially when trying to explain the difficulties their own countries are experiencing. However attractive such claims may be, they reflect only a small part of the truth. The influence of external forces certainly exists. But thinking that they alone determine everything points to a deeper misconception—politically, psychologically, and socially.

Global Power and Absolute Control

No one denies that the United States is a powerful actor in the international system. Its economic power, financial networks, military technology, and tech giants set the standards in certain areas. Therefore, its “influence” is real. However, equating “influence” with “absolute control” is incompatible with the complex structure of today’s world. Power in the 21st century is fragmented. The rise of China, the economic weight of the European Union, the demographic and technological potential of India, and the emergence of regional powers such as Turkey have made the global game multilateral. Therefore, no country can impose its interests uninterruptedly across every region. Local balances, societal reactions, and internal dynamics are always decisive.

There are also structural reasons for the limitations of global powers. The international system is too multi-centered to allow a single actor to establish absolute dominance. Economic relations create interdependence. A country’s complete manipulation of trade, energy, and financial networks also increases its own costs. Military power is limited in its capacity to produce political outcomes. Occupation or coercion is possible. However, creating lasting political transformation is often impossible. The cost of geopolitical maneuvers is high. Every intervention brings economic, diplomatic, and social consequences and cannot be sustained for long. Therefore, even major powers can exert only limited influence in regions where local dynamics offer resistance.

External Powers Are Important, But Are They Everything?

In international relations, ignoring external actors is not realistic. Countries’ foreign policy moves and regional calculations can affect domestic politics. However, when we attribute excessive significance to the influence of external powers, we stop analyzing our own internal structure and social realities. The most decisive factors in shaping a country’s orientation are not external pressures but rather its social structure, economic balances, cultural codes, institutional capacity, the political maturity of its citizens, and historical memory. External forces are effective only to the extent that they find resonance internally.

Examples from recent history illustrate this. During the Arab Spring, the policies of external actors were widely discussed. However, the real factors that brought millions into the streets were the economic injustice, unemployment, corruption, and political repression within those countries. The leftist waves in Latin America were shaped not by the preferences of external powers, but by income inequality in the region and the pressure created by local social organizations. The rise of nationalist movements in Europe was also not the result of a plan by external forces; it was the product of globalization, immigration policies, and the growing concerns of the middle class. These examples demonstrate that, despite the existence of external influence, the decisive power often comes from within.

So Why Is This Perception So Widespread?

There are many historical, sociological, and media-related reasons why the belief that external forces determine everything is so widespread. First and foremost, in many countries, past coups, economic crises, allegations of covert operations, and memories from imperialist periods create a natural ground for suspicion toward external actors. The marks left by historical traumas on the social consciousness often make today’s events prone to being interpreted as “external forces at work again.”

In addition, today’s information ecosystem amplifies this perception even further. Social media platforms have created an environment where unverified information and exaggerated commentary circulate rapidly. Complex economic or political problems become more tempting to interpret through much “simpler explanations.” The invisible plans of external forces offer a narrative that is both fast and attention-grabbing. For instance, unverified news spreading via Twitter or TikTok can shape social perception independently of actual events. Another reason is the structural characteristics of political culture. In countries where democratic institutions are weak, decision-making processes lack transparency, and the media is polarized, people struggle to trust their own governments. Distrust in the state naturally leads to an increase in the perceived influence of external actors. The idea that “if our institutions are this weak, of course external forces are calling the shots” spreads more easily in such environments.

Of course, international power asymmetries are real and feed perceptions. The economic and military weight of the US, the EU, or other major powers creates the impression in most people’s eyes that they “have the power to do anything.” However, being effective does not mean determining everything. For example, although the US has a large military presence in Syria, it has not been able to steer political outcomes in the region as it wished. This demonstrates the limitations of asymmetry. When the aforementioned factors come together, the influence of external powers is interpreted in an exaggerated manner. This perception is not entirely unfounded. However, the reality is much more complex, multi-layered, and multi-actor. Seeking power only externally means ignoring political and social will and internal dynamics.

Internal Dynamics, the Perception of External Forces, and Becoming a Social Subject

So why do people ignore internal dynamics and attach such great significance to external forces? This perspective creates a kind of psychological comfort zone. Shifting the responsibility for social problems elsewhere relieves individuals and political actors of their own obligations. For instance, if economic problems are widespread in a country, democracy is weak, or institutions are dysfunctional, explaining it with the phrase “because of external forces” is both easy and comforting. Thanks to this approach, there is no need for self-criticism, the responsibility to fix institutions disappears, the accountability of political actors is forgotten, and the demand for social change is postponed.

Another consequence of this perception emerges in the political arena. Constantly referring to external forces provides a basis for evading responsibility and legitimizing failures. When every problem is explained as “the game of external forces,” both accountability weakens and the performance of state institutions becomes impossible to monitor. For example, explaining shortcomings in education with the argument of “international pressures” obscures the deficiencies of teachers and education policies. Explaining economic crises with “foreign interventions” makes it easier to avoid questioning financial and structural decisions. Similarly, attributing political decisions to external interventions silences citizens’ critical voices and weakens social organization.

Explaining everything with external forces unknowingly feeds another danger: it weakens the belief that societies can determine their own future. As the idea that “others are already governing us” takes root, people lose confidence in their own political will. This reduces democratic participation, weakens the hope for change, and lowers social energy. For example, constantly attributing the causes of economic crises or social inequalities to external actors reduces citizens’ motivation to find solutions. Similarly, attributing political failures to external interventions prevents questioning the performance of state institutions and weakens social control.

In fact, although the discourse of external forces provides psychological relief at first, in the long run it creates a cycle that undermines social responsibility and participation. This perception weakens the capacity for agency at both the individual and societal levels. The real solution lies in recognizing this cycle and addressing problems through internal structural and institutional deficiencies. Structural strengthening in the areas of education, media, state institutions, and social organization increases citizens’ capacity to exercise their own will. This reduces dependence on external influences and strengthens social will and the capacity for agency.

A Multi-Actor, Multi-Layered World

Today’s international relations are not a game controlled from a single center. It is a complex and multi-layered system in which states, multinational corporations, international organizations, social movements, and regional power balances intersect. International relations theory defines such systems as “multi-actor” and “multi-level”: power does not derive solely from military or economic capacity; it is also shaped by cultural interactions, institutional capacity, and the ways in which societies organize themselves. Therefore, no actor can possess absolute control on its own; every move is limited by the reactions and counter-moves of other actors.

Concrete examples clarify the situation. External actors’ policies were influential in the Arab Spring, but the real factors that brought millions into the streets were the economic injustice, unemployment, and political repression within those countries. External forces may have intervened in the Brexit process. However, the fundamental factors determining the decision were local economic concerns, immigration policies, and political polarization. The leftist waves in Latin America cannot be explained solely by external interventions either. They were shaped by income inequalities, social organization, and popular demands in the region.

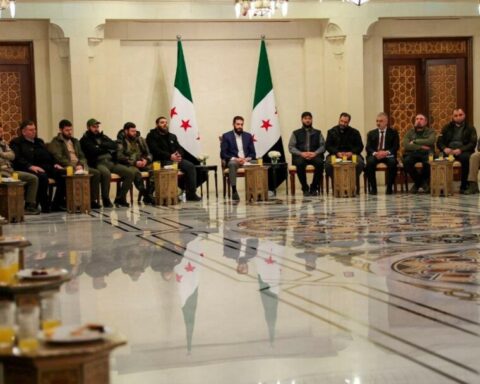

The resolution processes that Turkey initiated to solve its own terrorism problem were not processes directed by external powers either. On the contrary, they were shaped by Turkey’s own political will, social expectations, and the assessments of the state. Similarly, the claims that the Syrian revolution was organized by Western powers are inconsistent with historical reality. The main factor that triggered the revolution was the Syrian people’s response to years of political oppression, economic poverty, and a crisis of representation. Such reductionist approaches both ignore social will and weaken analytical depth by attributing complex political processes to a single external center.

In this context, choosing a single external focus to explain a country’s fate is both analytically insufficient and tantamount to underestimating social will. External powers can be influential. However, this influence is often dependent on internal dynamics. Economic vulnerabilities, institutional capacity, social organization, cultural codes, and political consciousness determine the extent and direction of external influences. Therefore, the international system is multi-actor, and the real power that determines a society’s future is the magnitude of its own internal dynamics and collective will.

Societies That Determine Their Own Future Are More Free

If we want to make more accurate analyses, we need a perspective that evaluates both external factors and internal dynamics together. External powers can be influential in global balances. However, without societies’ own internal dynamics and institutions, these effects cannot be permanent or decisive. But there is one truth we must never forget in this assessment: the will of the people, the level of consciousness of societies, and the strength of institutions are much more decisive than external interventions.

Of course, let’s talk about the influence of external forces—but without forgetting our own will. Let’s analyze global balances—but let’s do so without shifting the responsibility to others. Let us take external pressures seriously—but knowing that the real power shaping our future lies within. Because real power is often not outside, but hidden in the minds of societies, in their own institutions, in their own will. In short, producing excuses and ignoring the real power means both disregarding the will of the nation and siding with the continuation of the vicious cycle that emerges.

As a society trusts its own institutions, the scope of external influences narrows; as it strengthens its internal dynamics, it becomes less susceptible to external manipulation. The conscious participation of citizens, their critical thinking, and their involvement in decision-making processes are the most important internal resistance mechanisms in limiting external influences. In other words, strong internal dynamics and institutions form the most effective resistance against external powers.

At this point, it is worth mentioning two issues. The first is that being sensitive about positions regarding external powers is essentially a positive attitude. However, when the issue is exaggerated and turns into a conspiratorial perspective, the content and impact change. This leads to a comfort zone of explaining everything with this, a lack of self-confidence, and a sense of powerlessness that says, “whatever we do is useless.” The second issue is the reality that the real need is to build structural resistance internally, as much as to talk about external forces. The real solution lies in structural steps such as establishing independent and effective institutions, ensuring the education system supports critical thinking, promoting media literacy, making transparency and accountability standard, and increasing citizen participation.

Societies that strengthen their internal structure become not only more resilient to external pressures, but also free societies with a high capacity to determine their own future. External forces exist in every era, but the real power that determines the future of societies is always the strength and consolidation of the will within.