China is rapidly expanding its influence through the Belt and Road Initiative, investing $25 billion in Central Asia in early 2025 alone.

Analysts warn that regional connectivity must be balanced with security cooperation.

The infrastructure boom raises risks of smuggling, trafficking, and transnational crime across increasingly open borders.

When war in Afghanistan ended in 2021, the Central Asian republics could now focus on investments in human development and physical infrastructure without the prospect of violence spilling over the border from Afghanistan.

One of the republics, Uzbekistan, pursued what Yunis Sharifli has called a “multi-vector transport strategy” coupled with a “good neighbor” foreign policy.

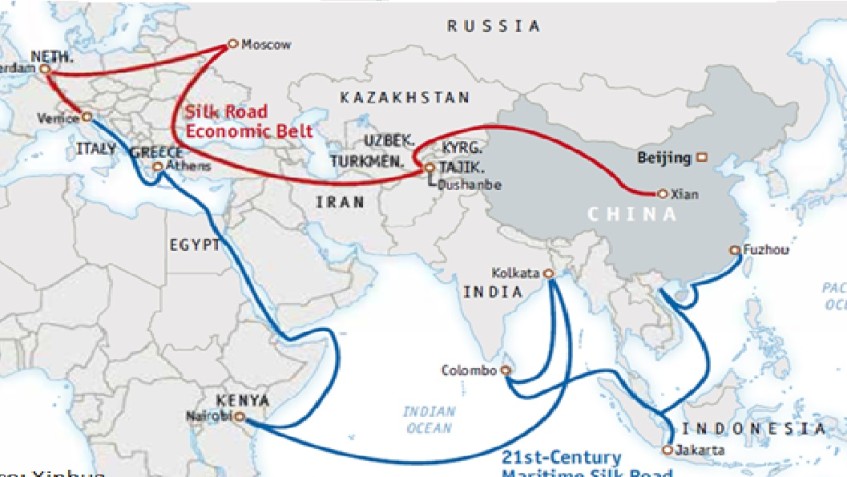

The region has seen many proposed regional transport links, such as the Kabul and Kandahar corridors through Afghanistan to Pakistan, the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, the China-Kazakhstan railway, and the Intentional North-South Transport Corridor, and the Middle Corridor.

Though these corridors will facilitate investment and trade, they are a significant incentive for smuggling and illicit trading.

The International Institute for Central Asia in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, recently queried “whether greater connectivity could create new vulnerabilities for the movement of illicit goods, extremist networks, and transnational crime.”

The smugglers – they are really transport specialists – may move narcotics today, weapons next week, then branch into humans, rare animals, and antiquities. As a side note, antiquities trafficking may be a new concern for Uzbekistan as it raises its profile as a destination for cultural tourism and the restoration of historic sites.

Presidents Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan and President Tokayev of Kazakhstan had successful meetings with U.S. President Donald Trump that were capped with, as Trump prefers, the announcement of big contracts for U.S. businesses. Both presidents invited Trump to visit their countries.

But there was another meeting in September that got less attention and fewer tweets: the director of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation met Pakistan’s Federal Minister of Interior and Narcotics Control, and we can anticipate more cooperation and intelligence sharing between American and Pakistani police.

The republics should explore if increased cooperation between the U.S. and Pakistani security services can be expanded to a region-wide effort to ensure the region’s investment in transport does not facilitate new criminal activity. Terrorists and criminals are using trans-national networks to do their business, so the region’s governments must attack the problem at the trans-national level.

Since NATO left Afghanistan in 2021, the Afghan Taliban have busied themselves with governance and re-imposed the ban on the harvesting of opium poppy, which was harvested in increasing amounts through the 2001-2021 NATO occupation. Poppy production is down, but it has not been eliminated, and has moved to Baluchistan in Pakistan and Badakhshan province in northeast Afghanistan, which borders on Tajikistan.

Tajikistan is the traditional route of narcotics bound to Russia and Europe, but if the smuggling networks can take advantage of smoother roads and modern airports and rail links, there is no reason they won’t pivot West to Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan.

And it’s not a problem unique to Central Asia. In North America, the U.S. Department of Justice reports, “Virtually every interstate and highway in the United States is used by traffickers to transport illicit drugs…” Likewise, in Canada, Ontario’s Highway 401 Corridor is a major human trafficking route.

And the narcotics that pass-through transit countries aren’t just someone else’s problem: the smugglers usually pay for local services with drugs instead of cash, and those drugs are consumed locally and create future customers for the narcos, so the transit countries are not immune to the problem.

And aside from increasing demand for their product, the narcos will do the other thing they do so well: seeking and finding the corrupt public officials they will need to facilitate their operations.

President Trump likes dealing directly with other bosses, and he appeared to enjoy his meetings with Presidents Mirziyoyev and Tokayev, but he still has work to do.

The American motion picture director Woody Allen said, “Eighty percent of success is showing up” and it is no different for politicians.

No U.S. president has visited Central Asia, but Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping have: Putin has made 77 visits, and Xi has made 15 visits to the region.

But China has made it a priority to engage with Central Asia’s leaders.

In 2023, China hosted the leaders of the republics at the two-day China-Central Asia Summit in Xi’an. In 2024 Xi visited Astana, Kazakhstan, for the 24th Meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). And in June 2025, Xi again traveled to Astana for the second China–Central Asia Summit, and pledged China’s “eternal friendship” with the region

At the September 2025, SCO summit in Tianjin, China, Xi met one-on-one with all the leaders of the republics. In the official picture of the meeting attendees, the five republics’ presidents are standing in the front row, a clear signal of China’s intent.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is the primary way for China to connect with Central Asia. When BRI outbound investment dipped in 2020-2022, we were told by Washington, D.C. authorities (here, here, and here) BRI was failing to achieve its goals and China’s officials had wasted a trillion dollars. However, we may have been misinformed…

According to the China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2025 H1, the first half of 2025 (2025 H1) saw the highest engagement for any six-month period ever, with US$66.2 billion in construction contracts and US$57.1 billion in investments (greater than BRI engagement in all of 2024 which was US$122 billion.) BRI set new records in oil and gas, coal, green energy, metals and mining, and technology and manufacturing. Also, “BRI investments in 2025 were driven by private sector companies,” not state-owned enterprises.

According to Inside China Business, “the program [BRI] had merely shifted, to different regions, and to investments higher up the value chain.”

BRI’s total engagement since program start in 2013 now totals US$1.3 trillion.

Of that record first-half engagement, US$39 billion went to Africa and US$25 billion went to Central Asia. That’s pretty stunning on a per capita basis as Africa’s population is about 1.5 billion and Central Asia’s is about 84 million.

China obviously believes “eternal friendship” is nice, but its better if it rests on a foundation of investments rather than declarations just good fellowship.

If Trump visits Central Asia he will be seized by the rapid pace of development in Tashkent, though he will probably take it upon himself to critique the construction in New Tashkent City.

But it will also be an opportunity for him to learn that just because the American troops are out of Afghanistan, Afghanistan’s neighbors can’t relax.

The region’s leaders can explain how they are ensuring the region’s development doesn’t give the bad guys more opportunities to be bad. The region must balance greater openness with greater security cooperation. That will include ongoing cooperation by the region’s governments with the European Union (EU), the U.S., Russia, China, Azerbaijan, Türkiye, and, yes, Afghanistan and Iran.

All that fine 21st century infrastructure will improve the region’s quality of life and make it more attractive for foreign direct investment, but it will also ease the ability of organized crime to commit crimes. It is also attractive to terrorists and extremist groups that can graduate from bombing a police station to bombing an oil refinery or water treatment plant.

China has, as we say, put its money where its mouth is. Beijing obviously sees stability in Central Asia as key to China’s stability and is prepared to make outsized investments to secure its western flank, both to ensure quiet in its western provinces and to refine overland transport routes that avoid maritime chokepoints at Malacca, Singapore, Hormuz, Bab al-Mandeb, Suez, and Gibraltar.

In the U.S. Strategy for Central Asia 2019-2025: Advancing Sovereignty and Economic Prosperity, Washington says all the right things about sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity, but will that hold now that BRI is again on an upward trajectory? When Washington digests the fact that Central Asia is getting “more China,” it will test the region’s multi-vector foreign policy.

Washington will have to resist the urge to use Central Asia as a platform to attack Afghanistan and Iran, or attempt follies like retaking Bagram Airfield. U.S. meddling will see a vigorous, asymmetric response from China if it fears its investments and interests are under threat.

Russia has recognized the Taliban government, China has sort-of recognized the government, and Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are actively developing trade and investment projects with Kabul, and both capitals envision trans-Afghan trade routes that connect Central Asia to Pakistan.

China will be suspicious if the U.S. actively encourages regional cooperation and will assume Washington is building an anti-Beijing coalition to destabilize Xinjiang. But the U.S. has an interest in ensuring the surety of East-West trade that benefits its European allies and that connectivity projects like the Middle Corridor succeed. In fact, Washington should explicitly solicit Beijing’s cooperation in attacking criminality and extremism that will exploit greater connectivity.

With active regional security cooperation and select assistance from the U.S. and EU, Central Asia can counter the downsides of greater connectivity, increase attractiveness to investors, and make up for the “lost decades” of 2001 to 2021, when the region’s economic and social development was delayed as the leaders were more focused on the possible spillover of violence and extremism from Afghanistan.

* James D. Durso is the Managing Director of Corsair LLC, a supply chain consultancy. In 2013 to 2015, he was the Chief Executive Officer of AKM Consulting, a provider of business development and international project management services in Central and Southwest Asia to U.S. clients in a variety of industries including telecommunications, homeland security, and defense. Since 2013, he has mentored graduate students at The George Washington University, Elliot School of International Affairs on the roles of members of the Country Team at an American embassy, security assistance, and the functions of military advisors attached to an embassy.