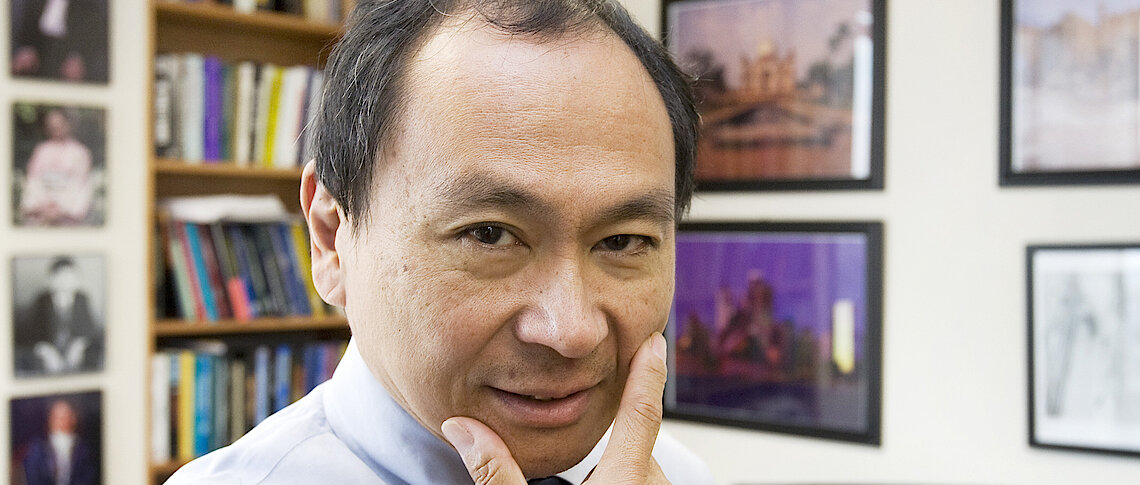

In my memory, Francis Fukuyama is someone who constructs shortcuts and facile connections between philosophy, science, history, and political thought—someone in pursuit of statements and inferences that will carry him to fame without understanding or honoring the value of thinking itself. Recently, I came across yet another lengthy article of his on our website (https://kritikbakis.com/en/bringing-human-nature-back-in/ ), and once again I was overcome by the same feeling. When I saw him speaking—as if it were something significant—about his book Our Posthuman Future, I remembered what I had written about that dreadful book ten years ago.

Francis Fukuyama, whose reputation is now in tatters, is the author of the 1992 thesis The End of History. Ten years later, he published yet another book in line with that absurd thesis, titled Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. This book, which was swiftly translated into Turkish by METU Press, was fiercely criticized by us in an article titled “Only the Ignorant Speak—That’s the Problem!” (Virgül Magazine, September 2004 issue, and Psychiatry in Life, Pedam Publications, 2009). Let us see:

Only the Ignorant Speak

Since Fukuyama’s End of History thesis, there has been a broad consensus that he is one of the key minds of the intellectual cadastre working in service of American hegemony. That reason alone suffices to warrant attentiveness to what he says. However, Fukuyama’s new book also addresses issues that concern humanity as a whole—issues to which no intellectual can remain indifferent.

Fukuyama sides with the concept of “human nature,” which liberal ironists like Richard Rorty approach quite critically—that is, he believes that such a thing as “human nature” exists. Furthermore, he argues that the most significant threat posed by today’s biotechnology is its potential to alter human nature, thereby ushering us into a “posthuman” historical era. According to him, human nature shapes political regimes, and therefore, a technology possessing the potential to reshape us will lead to new political consequences.

Today, we face numerous problems such as genetic discrimination, the privacy of genetic information, and the multitude of issues raised by the completion of the Human Genome Project (HUGO). Yet in Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution, Fukuyama focuses on none of these issues. He treats all the claims and theses of biotechnology advocates as if they are not only possible but even proven. He discusses what may follow biotechnology as though a new kind of human has already been created, and those who control biotechnology can produce whatever type of living being or human they wish at any moment. By framing the subject in this manner, he emphasizes that the problems are not only ethical but also political in nature.

Since Ancient Greece, people have debated whether nature or nurture plays a more decisive role in shaping human behavior. But according to Fukuyama, just like “history,” this debate has now also come to an end. The master (!) believes that the future will provide almost indisputably precise empirical knowledge about the molecular and neural pathways from genes to behavior.

The link between heredity and intelligence, which is the subject of behavioral genetics and continues to spark heated debate in the scientific community; the efforts to ground criminal behavior in biology; and the claimed connection between genes and homosexuality—all of these are presented by Fukuyama as if they were already proven facts, in line with the claims of behavioral geneticists. As a great theorist (!), Fukuyama, of course, doesn’t fail to suggest that he is aware of opposing views. Yet he cannot stop himself from stating: “The fact that bad science in the past was used for bad purposes does not protect us from the possibility that good science in the future may serve purposes we consider good.”

In his view, as concrete molecular links are discovered between genes and traits such as intelligence, aggression, sexual identity, criminal tendencies, and alcohol addiction, people will begin to realize that this information can be used for social purposes.

To what extent can the widespread use of drugs that affect human emotions and behavior change human nature? Could the rise of psychotropic medications and the growing knowledge of brain chemistry and how to manipulate it lead to behavioral control with significant political consequences?

Fukuyama, rightly, claims that these drugs primarily influence the most politically significant emotions—namely, feelings of self-esteem—and frames his analysis accordingly. Self-esteem is a concept currently in vogue, especially in the United States, where people are constantly told they need more of it. This concept is related to a critical aspect of human psychology: the desire for recognition and approval.

Economist Robert Frank points out that what we often consider economic interest is in fact a desire for recognition of status. Hegel believed that the historical process fundamentally arose from a struggle for recognition. Fukuyama poses the question: “If people had just a bit more serotonin in their brains, might all the struggles throughout human history have been avoided? And if so, how would history have unfolded then?” Thanks to psychotropic drugs like Prozac and Ritalin, he believes that even without waiting for the great achievements of genetic engineering, it is already possible in today’s society to create a politically correct, self-satisfied, and socially compliant type of average androgynous personality.

Fukuyama, the True Believer in Biotechnology

Fukuyama, who asks such childish questions about history and engages with history and philosophy only superficially—defending ideas that no one even slightly familiar with the realities of psychological sciences or psychiatry would dare to express—has complete faith in biotechnology. According to him, there is no need for lengthy philosophical debates or for the full emergence of human genetic engineering to justify this faith. A few drugs that affect human behavior have been discovered—surely, that’s more than enough!

Yet what we know about how Prozac and Ritalin work, how far their effects can extend into different realms of human behavior, and especially how they might impact so-called “normal” people is just a drop in the ocean compared to what we do not know. Substances that affect human behavior have existed throughout human history; however, no sound-minded thinker has ever demonstrated the kind of ignorant audacity that Fukuyama exhibits. That is, except for the comical media minds who attempt to explain the Hasan Sabbah incident or certain modern terrorist acts through the “substances” those individuals are claimed to have taken…

According to Fukuyama, one way contemporary biotechnology may affect politics is through the extension of human life expectancy and the resulting demographic and societal changes. Even if only half of biotechnology’s promises in the field of gerontology come true, Fukuyama states, half of the population in developed countries will reach or exceed retirement age. Another American thinker, Lester Thurow, constructs the framework of his book The Future of Capitalism around the reality of increasing human lifespan. However, when it comes to exaggerating the relationship between biotechnology and life extension, Fukuyama’s ignorant boldness knows no bounds. For him, the political significance of human lifespan extension lies in this: within two generations, the dividing line between First and Third World countries will not only be based on income and culture but also on age.

Then, once again, he poses a fantastical question: “Might the world be divided into two parts—one, the North, where politics is determined by elderly women, and the other, the South, ruled by what Friedman calls ‘super-empowered angry young men’?”

Fukuyama defines genetic engineering as the path to the future and the final stage in the development of biotechnology. The application of genetic technology to agriculture was termed the “Green Revolution” and presented as a solution to hunger. According to him, the next inevitable step in this advancement will be the application of this technology to human beings.

But Fukuyama’s faith in genetics does not stop there; he even goes so far as to claim that the greatest reward of modern genetic technology will be the creation of “designer babies.”

However, according to this great (!) mind, some significant obstacles must be overcome before humans can be genetically altered in this way. The first is the complexity of the issue; the second is the ethical dimension of experimenting on humans.

Fukuyama’s faith in genetics shows no hesitation. What occupies his mind most is the “transformation of human nature”; whatever he discusses, he always circles back to this. He simply cannot accept the possibility that the predictions of genetic engineering may not come true. He believes that—even if delayed—the transformation of the human species will eventually occur, and even if the kind of genetic engineering that could affect the species as a whole doesn’t happen for another fifty or even a hundred years, it will still be the most important development in the future of biotechnology.

He is preparing himself for that great (!) day when human nature will be transformed. Because with the transformation of the human species, history itself will end and a new cycle will begin. And Fukuyama considers himself the first and greatest theorist of this new era—an era in which the concepts of justice and morality will inevitably undergo radical change. Deep down, this is the mission he assigns himself.

Benevolent Eugenics

Having thus (!) illuminated the possible paths to the future, Fukuyama poses one last question to allay our final concerns: Why should we worry? (Is the specter of the eugenics movement rising once again?) The term eugenics was first coined by Charles Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton. Eugenics is the deliberate breeding of desirable types of offspring in order to enhance selected hereditary traits. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, state-sponsored eugenics programs enjoyed broad support.

According to Matt Ridley, the main problem with past eugenics laws was precisely their being backed by the state. Like Ridley, Fukuyama is of the opinion that if individuals pursue eugenics of their own free will, it would not result in similar harm. Thus, we might be moving toward a softer, more benevolent form of eugenics—one that doesn’t provoke the usual horror.

But unlike Ridley, Fukuyama proposes replacing the term “eugenics,” which he believes carries too many connotations, with the term “breeding,” which corresponds to Darwin’s term “selection.” The term “breeding,” he argues, more accurately reflects the future potential of genetic engineering: by allowing us to choose which of our genes we pass on to our children, it carries the potential to eliminate certain human traits altogether. After all, our master (!) theorist would never deny us the refined courtesy of not rubbing in the crudeness and brutality of liberal eugenics.

Fukuyama does not hesitate to add that what biotechnology will eventually put at risk is “the human moral sense”—a value that has remained constant since the beginning of humanity. He emphasizes that Nietzsche is a good guide in this matter. By using Nietzsche as a shield, he effortlessly removes the moral barrier standing in biotechnology’s path.

There are many aspects of human nature that we believe we understand and would wish to change if we could. Understanding the good and evil within human nature is deeply complex. Fukuyama stresses that we must sincerely accept the consequences of abandoning our natural standards of right and wrong, and recognize—as Nietzsche did—that doing so could take us into territories most of us would never wish to enter. Our great (!) thinker believes that Nietzsche’s invitation to a true morality beyond good and evil convinces us to accept all the moral consequences of transforming human nature.

So, what should we do in the face of biotechnology, which will inevitably blur the lines between potential benefits and overt or hidden threats? Fukuyama believes the debate is taking place between two groups: libertarians who want to permit everything, and those who seek to ban broad areas of research and application—among whom he includes Jeremy Rifkin and the Catholic Church as examples.

In his book The Biotech Century, also translated into Turkish, Rifkin argues that we were late in recognizing the consequences and costs of the physics and chemistry revolutions of the previous century, and that this time we must be prepared. In saying so, he voices what we consider to be the common intellectual concerns of thoughtful individuals and offers a highly reasonable perspective. Knowing that Rifkin is not easily countered, Fukuyama avoids engaging him directly. Instead, he pursues a poor strategy by lumping him together with a Catholic conservative.

Although he clearly belongs to the laissez-faire camp, Fukuyama insists that he is a “moderate” in this debate. What supposedly makes him a moderate is his advocacy for using the power of the state to resolve these issues. And if that proves to be beyond the capacity of any individual nation-state, he argues, then it must be done on an international level.

But where should the line be drawn? Then again, a question implying concern about “limits” probably shouldn’t be posed to someone like Fukuyama, who recognizes none. After reading such unrestrained views, we no longer feel any inclination to ask Fukuyama about boundaries. In his world of thought, it is all too clear that someone who knows nothing cannot know their limits, and someone who does not know their limits is capable of saying anything.

The First Popular Introduction to Posthuman Ideology

Yes, Fukuyama is a poor-quality thinker whose only skill lies in caricaturing the worlds of science and thought for popular appeal, while frequently putting forward erratic political views. The ideas in his book Our Posthuman Future are so absurd and unscientific that they’re hardly worth dwelling on.

Our main reason for engaging with him is his connection to the concepts of “posthuman” and “transhuman.” Fukuyama’s book is one of the earliest works on this subject and, from the very beginning, reveals his ties to the deep structures of the United States.

Although the book has been translated into Turkish as İnsan Ötesi (“Transhuman”), that translation is incorrect. İnsan Ötesi corresponds more closely to transhuman, whereas Fukuyama deliberately uses the term posthuman in the title—precisely because he sees transhumanism as one of the most dangerous ideas in the world.

And as our readers well know, the idea of the posthuman is one of our major adversaries—and we will be grappling with it far more seriously in the future.