Türkiye’s land-based knightly character can create a new geopolitical opening by reaching the high seas, which the Germans and Russians could not do due to geographical reasons, and the open celestial sea and can pave the way for a different historical leap, a rebirth. Only then can a truly rationally thinking, universally horizoned, creative and productive, brave and free human quality and, as a result, state quality level be achieved. Only through such a radical change, the meaningless and vicious discussions produced by the existing character and conditions are overcome and a concentration of personality and an asabiyyah of dignity that is in line with the direction of the real world is formed. This would mean a genuine moral revolution.

For the New Century; A Critique of Society

Abstractions about the structure of societies certainly do not reflect the whole reality of those societies. However, all kinds of abstractions still help us to grasp the important and dominant aspects of social phenomena.

An abstraction regarding Türkiye’s social characteristics—despite exceptions depending on time and circumstances—can help us comprehend the dominant features of the existing realities. This effort at abstraction also involves the accurate identification and critique of traits shaped by historical and social conditions. This critical abstraction has been one of the fundamental dynamics in transitioning from military-agrarian systems to the industrial age and then to the information age.

The critique of society, especially since the Tanzimat era, has also produced counter-reactions, generating a conservative faction in the society that’s efforts based on the defense of the old. The two-hundred-year conflict between the Western-innovative segment and the status quo conservative segment has produced a society that is physically and mentally tired and discouraged, and has made permanent a ‘bureaucrats’ reflex with constant concerns for security, existence and survival. However, development and progress are possible not with these negatively charged state and society characteristics, but rather in a self-confident, free and critical habitat.

By any means, Türkiye spent the last two hundred years in this chaotic turbulence, sometimes advancing, sometimes falling, but suffering many casualties. The brightest children of society have been sacrificed to policies born out of these pathological security concerns, even when much simpler solutions were available. National wealth has been squandered in mostly fabricated internal conflicts. Intellectual capital has been consumed in absurd contradictions and conflicts, thrown into futile ideological pits. As a result, a schizophrenic society has emerged, where everyone idolizes a particular historical moment while demonizing what came before or after.

The state and the various ideological, ethnic, and religious organizations that appear to oppose it but are, in reality, its reverse imitations, have collectively transformed the country into a vast pagan-pantheon. In this pantheon, where everyone forced everyone else to worship their gods, but in reality no one really believed in anything, gods, idols, holy figures, immortal leaders, messianic saviors, taboo concepts, fetishized words and idols made of halva, paper and clay existed only as instruments of domination or revenge, and ‘truth’, ‘reality’, justice, originality, naturality and universality were reduced to mere tools of utilitarian value.

Stopping this social destruction, which continues as a continuation of the political destruction of the Ottoman Empire, should be the most important intellectual effort today. All idolatrous ways of thinking that have led to this destruction, all false concepts of contradiction and conflict (republic, religion, secularism, sect, ethnicity, etc.), all vicious partisanship styles must now be invalidated.

In this context, critical thinking must cease to be merely an intellectual charisma tool and instead become an essential social virtue that permeates every layer of the state and society. If Türkiye fails to create a new habitat where all forms of idolatry are disdained and only concrete truths and genuine goals are upheld, it will once again miss the opportunity of the new century, and all the positive potentials inherited from history and geography will be sacrificed to these meaningless conflicts.

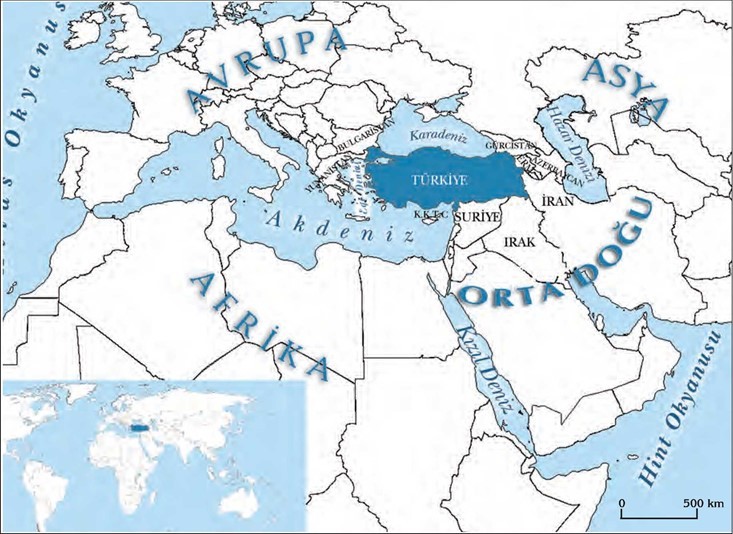

In the critical analysis of society, the central problem is the army-nation character and the fundamental deficiency is the land-based geopolitics far from the sea. These characteristics are almost like a common national trait of the Turkish society with all its different ethnic-religious-sectarian diversity. While these traits are the source of many problems, they can also be regarded as the basement for many potential solutions.

The Military-Nation: Allegiance to Power, Authority and Status

Ahmet Mithat Efendi, one of the intellectuals of the Tanzimat period, summarizes this national character based on the society’s lack of skill in commerce and the arts: ‘History shows us that our initial emergence was in the form of a military nation. Indeed, although we have displayed considerable skill in industry and managed to expand our commercial reach to some Mediterranean coasts, we cannot deny that these achievements have been predominantly driven by our non-Muslim subjects rather than the Turkish and Muslim population. If we compare the proportion of the Muslim military element within our nation to the number of soldiers we have deployed in various wars, it becomes clear that until quite recently, and perhaps even today, we have been a nation in which everyone is considered a soldier. The saying “A Muslim who does not belong to the Janissaries, Sipahis, or other military classes is not truly a Muslim” has long held significant validity. However, the progress of industry and commerce is only possible in times of peace—ideally, perpetual peace—and we have spent very few years in such peace.’ (Ahmet Mithat, Ekonomik politik, Quoted by Şerif Mardin, Siyasal ve Sosyal Bilimler, İletişim Publishing, 1992, p.92)

Alongside this national character, in the eyes of the people, the military is the “Prophet’s Hearth” and the essence of the state. It is the guarantor of existence, survival, homeland, and nation. The arrival of the Seljuk beys and the Ottoman principality in to the Anatolian region, their hold on the region, their assuming the role of the sword of Islam and their subsequent establishment of political hegemony were all achieved through the spirit of gaza (the holy war) and fetih (the conquest). This warrior tradition persisted even through the state-formation stages, with warfare and its related professions becoming the primary occupation and means of livelihood for the Muslim population. The Ottoman Empire left trade and craftsmanship largely to non-Muslims. Perhaps for this reason, many historians emphasize the role of the economy—monopolized by non-Muslim minorities and dependent on the West—as one of the key factors in the empire’s decline. The roots of this dominant characteristic lie in centuries of life under a semi-military order. This is the reason for the special importance given to and loyalty displayed to the state and the army.

Unlike the autonomous areas of wealth and the class-based society structure that shapes it in Western societies, a structure in which power and status are concentrated in the state, dominates Turkish society. It is a well-known historical fact that during the Ottoman rise, the primary focus was on strengthening the state and the military, and in times of decline—something still evident in all political circles today—the instinct was always to first “save” or “correct” the state. This central role of the state, representing authority, and the army, representing its power, has not only been created by the pressure of actual needs, it has not remained a temporary situation, but has become a powerful ideology that has permeated the social imagination.

In this sense, it is more realistic to analyze Turkish society not through a class-based or circular center-periphery dichotomy but through a pyramidal center-base model. Society can be explained through a structure that descends from the top (rulers, status holders, authority) to the bottom (subjects, commoners, the ruled). The center is at the top, and the periphery is at the bottom. The state and the people, rulers and ruled, elite and masses—these categories are defined not by class or ethnicity but by their relationship to the state. This hierarchical structure fundamentally expresses the uncontested hegemony of authority and status (the military and the state) over the people. Allegiance (biat) to the center, to those positioned above, is both a religious and customary obligation. In this sense, the state and the military are religious institutions, and religion that is, the real Islam that the majority of the society actually believes in and lives by, is statist and militarist. This formula was also valid for the relationship between Christianity and the Byzantine Empire in the Orthodox Eastern Roman tradition. Perhaps, in these lands, the nature, legitimacy, and survival of the state fundamentally depend on this religiosity.

Taking this reality into account, a restoration that incorporates the possibilities of the new era can be envisioned through a perspective that sees the military-state and military-nation not as a problem but as an opportunity.

Forms of allegiance to power, authority, and status, when rooted in religious foundations, facilitate consent-based obedience. But for the same reason, they also legitimize dissent and rebellion. When the state deviates from justice, the door to objection opens.

On the other hand, while bureaucratic statuses, that is, the high or low-level authorities in civil service system, keep the state’s wheels turning thanks to an influential segment formed by social selection, partially autonomous areas, hidden cadres, and a different social and economic concentration area are formed in the civil sphere outside the civil service. The state’s primary security concerns stem from the growth of these civilian spheres beyond its control and oversight. Many of the so-called religious, ideological, or ethnic conflicts are in fact the political manifestations of these uncontrolled social factions. Every time the state suppresses civilian spaces in an attempt to enforce order and control, political mobilization outside state control increases. This paradox disrupts the balance between freedom and security. When security suppresses freedom, it increases the security problem. Whenever freedom provides security, establishing security becomes easier. Because peace and order is a state of security in which there is security of life, property, honor, mind and generation, and this already means safety. In an environment where rights and the rule of law are upheld, obedience to the state’s bureaucracy becomes a legitimate necessity. In this sense, religiosity serves as the glue binding the state-society relationship in these lands. Otherwise, whenever the state restricts freedoms and violates the rights of individuals or groups, this glue dissolves, and disorder ensues.

The more autarchic, that is, self-sufficient, the power of society in civil areas, the more solid both freedoms and security will be. Therefore, if the state’s control and oversight of civilian spaces shifts from being a mechanism for stability to becoming an imposition of political-ideological-class interests or the suppression of dissent, the state loses legitimacy and turns into an instrument of the ruling elites against society. In this regard, it has been said that the state’s religion is justice, and the principles of the rule of law have always been upheld as the ultimate standard.

The formula of security and consequent freedom in exchange for a fee (tax) inherent in military agricultural empires continues, with some variation, in the modern era. Although more comfortable measures may be periodically implemented in some countries located on the American or European continents where internal and external threats are minimal, this comfort is disrupted when conditions such as economic crises, external threats, or immigration-related social issues arise, ancient rules come into play. In other words, liberal democratic dogmas may work on paper, but they collapse in the face of real-world problems.

With its military-nation character, hierarchical political pyramid, and society’s deep-rooted allegiance to power and authority, Türkiye must solve its problems within the framework of the state, in a geography where social, economic, and ideological contradictions are constantly reproduced. The realities expressed in proverbs such as, either the state is in power or the raven is in carrion and, imam-congregation relationship do not indicate an ideal state but rather a fact that must be acknowledged. Despite all its statist, power-worshipping, and irresponsibility-inducing consequences, society’s attachment to the state and its voluntary or forced obedience remains the only mechanism for maintaining order. ‘The poor, unlike merchants, have no protector other than the state.’ Therefore, the solution to political and economic problems, as well as ethnic, sectarian, and religious issues, lies in the state returning to its essential nature—that is, being governed by justice and law (which is essentially what religion/sharia means), by strengthening the nation in civil spheres, ensuring that freedoms become the guarantee of security, and ultimately, by the state being embraced and owned by the nation. In this context, the soldier-nation will become the backbone of the state, not bureaucracy’s subjects, but an authority to which it is responsible and accountable. Only on this condition can the state exist forever.

The Land Knight and Fear of the Sea

‘….Later, Sultan Malik-Shah traveled as far as Samandağ (Süveydiye) and reached the Mediterranean. Watching the sea with great excitement, he gave thanks to God for ruling over lands even more extensive than in the time of his father, Alp Arslan, with the pride and excitement that these thoughts aroused in him, he rode his horse into the wavy sea, dipped the sword in his hand into the water three times and took it out, after saying, “This is what God has given me, the sovereignty of the countries from the Eastern Sea to the Western Sea,” he prayed and thanked God for this grace and mercy He had bestowed upon him. The sultan then collected some sand from the shoreline and, at a later time, traveled to his father Alp Arslan’s tomb in the city of Merv. There, he expressed his justified and proud feelings by saying, ‘O my father Alp Arslan, rejoice! The son you left behind as a child has now conquered the whole world.’ (İbrahim Kafesoğlu, Sultan Melikşah Devrinde Büyük Selçuklu İmparatorluğu, İstanbul, 1953)

For Sultan Malik-Shah, the world extended only as far as the sea. This remarkable story also reveals an important truth about the limitations of land-based geopolitics. In fact, even before the arrival of the Turks, the world of the region’s Arabs, Persians, Kurds, and other Muslim peoples was primarily confined to land. Except for merchant classes, seafaring was neither a livelihood, an area of curiosity, nor a security concern for those living near the Caspian, the Persian Gulf, the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, and the Indian Ocean. The fate of many societies living on land around the sea would change with the invasion of peoples who could cross the open seas from the 15th century onwards. Fear of the sea would bring about the feared.

The dispersed village structure that Doğan Avcıoğlu pointed out in the 1960s was eventually overcome through rural-to-urban migration and uncontrolled urbanization. But like many other issues, the aftermath of this correct policy was not taken into account and today’s village-like cities emerged. This process, which has rendered modern urbanization obsolete and left agriculture unattended, is now the basis for serious social and economic problems. This chaotic development is still the most important obstacle to the transformation of the people, who are struggling with the minimum subsistence difficulty, from the masses to the nation. Urbanization is not just an economic or political necessity; it is also a fundamental ground for religious and moral development.

On the other hand, for centuries, the Anatolian people, despite living on a peninsula, never ventured into the open seas beyond small-scale coastal fishing and thus never came to know the vast oceans. Unlike seafaring societies, they did not develop the courage to face the uncertainties and unpredictable dangers of the oceans, nor did they experience the sense of freedom and the thrill of constant exploration. (Even the Ottomans tried to establish a partial presence in the Mediterranean by hiring Mediterranean pirates.)

In contrast to societies with access to the open seas, where stability is challenged by the unpredictability of waves and winds, land-based societies are characterized by endless, repetitive conflicts between states, beys, pashas, bandits, and armies. In such a geography, it is a vital priority to demand that the most powerful one ensures peace and order, that is, stability and tranquility; this is the fundamental reason for the attachment to power, authority and status. In other words, “either the state is in power or the raven is in carrion”…

Geography is not destiny; it is an opportunity. When a land-based society fails to fully utilize its geography, it produces a character that is inward-looking and entangled in its own problems, unable to reach out to the world.

The reality of a military-nation is a direct consequence of being a land-based society, just as the existence of a military-state stems from the same condition.

The sea represents instability, shifting ground, and unpredictable winds. Navigating the vast waves according to the wind’s direction, unlike moving on solid land, requires entirely new skills, techniques, and a different level of self-confidence. Many of the survival skills developed over centuries in Eurasia’s vast plains, rugged mountains, and river valleys simply do not apply at sea. Moreover, the sea, especially the ocean, is full of uncertain and uncontrollable dangers, and very refined skills are required to navigate, find one’s way, and reach land.

It is essentially the character of sailors to complete a job with the same energy, desire and intention until the end. Because they have to reach land.

In contrast, land-based societies encounter countless variables between the starting point and the destination. More often than not, they are forced to struggle with unexpected challenges before ever reaching their goal. This is why land-based societies often begin endeavors with great enthusiasm but fail to see them through to completion.

Geographical discoveries enabled European peoples to cross the seas from Eurasia to the world and conquer the world. Europe owes its rise as a global power to maritime expansion, which shaped modern colonialism and capitalism. In contrast, the land-based geopolitics of Germany and Russia, unable to break through to the open seas, repeatedly suffered defeat at the hands of naval powers. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Englishman McKinder, who said, ‘who rules Eurasia rules the world’ was not proved right; the American Alfred T. Mahan, who said, ‘who rules the seas rules the world’ was proved right.

In the 21st century, however, Alexander De Seversky’s theory of ‘air supremacy’ has taken precedence.

In the century we live in, a further advancement of the postmodern era has begun, and the effort to transcend the celestial realm—that is, to conquer the skies and establish dominance in the heavens—has become the primary motivation for development. (The sky is a refined form of the sea. Even in ancient times, many cultures used expressions that referred to the heavens as a kind of sea. Today, words like ‘airport’ and ‘spaceship’ are used in the same sense. After all, air is simply water in vapor form. ‘It is not for the sun to catch up with the moon, nor does the night outrun the day. Each is floats in an orbit of their own.’ (The Holy Quran, Surah Ya-Sin, Ayah: 40.), ‘The death of fire is the birth of air, and the death of air is the birth of water.’ – Heraclitus.)

Military technology and the digital age it has fostered are now almost entirely built upon air power and the circulation-transmission of airwaves (frequencies).

Despite belated and successful efforts, countries like Türkiye, which have not yet surpassed a history shaped by land, are still far away from reaching the necessary equipment of the new age based on air-wind-frequency transmission, let alone crossing the high seas. Sea and air, which require new skills and a different self-confidence, are new opportunities for land-based societies to overcome their thousands of years of habits and become subjects again in the direction of the flow of history.

As a society, in a geography surrounded by seas on three sides, setting out to the ocean and embarking on an all-seeing, celestial sea voyage is a necessary condition for physical and spiritual change.

Türkiye needs policies that extend beyond coastal seafaring to engage in open-sea navigation, not only for security but also for economic and social expansion. At least 20% of the population should derive their livelihood from the sea and air, and at least 40% of the country’s intellectual energy should be focused on professions related to the maritime and aerospace age. It is imperative that the state’s security forces have greater naval and air power than land forces. An army of sailors and airmen will also make the military character more open-minded and capable.

Bridging a land-based past with a maritime and aerospace future can only be achieved through a natural process of evolution and transformation within the framework of the military-state and military-nation. Fear of the sea and air should not be seen as a limitation on the land-knight spirit, but rather as a challenge that provokes growth and expansion. Only then can history break free from its current siege in this geography and flow naturally once again.

Geopolitical vision is also the possibility of social transformation

These social characteristics of Turkish society perpetuate a totalitarian, statist order that aims to preserve the status quo and that both divides and obsoletes society. However, the same characteristics, with a different evaluation, can be transformed into a positive dynamic of development and integration in the new century.

By building upon past experiences and integrating traditional values with universal democratic principles, Türkiye’s social structure can be reinterpreted to produce a more advanced democracy.

Conditions such as a land-based society overcoming its fear of the sea, the transformation of the soldier nation character into a more disciplined and productive society, the transformation of the worship of power and status into a means of achieving more public goals, the conquest of the state with freedom and justice are the necessary conditions for the whole society to overcome the pain, defeat and trauma inherited from the last century and prepare for the new age. The military-nation character, much like how Japanese and German warrior cultures evolved, can serve as the foundation for a disciplined and principled rule of law, as well as a more productive economy. A purely military mindset, which prioritizes security above all else, can be redirected toward an understanding that security itself is built upon freedom, the rule of law, and economic productivity.

Dependence on power, authority, and status can be redefined into a social behavior focused not on personal connections but on individual labor, effort, and ability—one that requires responsibility, rational thinking, and performance-based merit.

The hierarchical structure of a pyramidal center with obedient subjects can be transformed into a state-nation dynamic, in which a strong civil society takes ownership of the state and holds it accountable.

Türkiye’s land-based knightly character can create a new geopolitical opening by reaching the high seas and the open celestial sea, which the Germans and Russians could not do due to geographical reasons, and can pave the way for a different historical leap, a rebirth. At that point, Türkiye could truly develop a rational, universally oriented, creative, and productive character, fostering a brave and free-spirited human quality, which in turn would elevate the quality of the state. Only through such a radical change, the meaningless and vicious discussions produced by the existing character and conditions are overcome and a concentration of personality and asabiyyah of dignity that is in line with the direction of the real world is formed. This would mean a genuine moral revolution.

These transformations are possible, but first, collective intellectual thought must begin to move in this direction. As ancient wisdom says, ‘what you are, so you believe, and as you think, so you are.’