Witnessing the Revolution in Syria

What I saw in Syria resembled scenes from a dystopian film. In this film dominated by yellowish earthy tones, what I witnessed during peace, civil war, and revolution felt like the eccentric work of an unpredictable screenwriter and director.

Most of the scenes were unbelievable, terrifying, shocking, and filled with drama. Yet, in keeping with the fate of this geography, they were also full of surprises. In these lands, everything could change at any moment; the script you expected could suddenly turn into a completely different story.

FIRST ENCOUNTERS WITH ASSAD

What first caught my attention about Bashar al-Assad were his tall stature, light-colored eyes, reserved demeanor, and cold spirit. I had first seen him during official programs in the period when Turkish-Syrian relations were good, as I was serving as Prime Minister Erdoğan’s press advisor. Between 2008 and 2010, we occasionally crossed paths—sometimes in Ankara, sometimes in Damascus and Aleppo. As I watched him from a distance, stories I had heard about his father Hafez al-Assad’s years of cold-blooded dictatorship ran through my mind. The son of the main perpetrator of the Hama and Homs massacres now stood just a few meters away from me, dressed in an elegant suit, seemingly trying to portray himself as a different person.

One scene remains vivid in my memory. While seated at a dinner table with Prime Minister Erdoğan, Assad suddenly turned his attention toward a woman standing at the entrance of the room and made a gesture as if to offer her a seat, prompting everyone to wonder who she was.

This middle-aged woman was Bouthaina Shaaban, a bureaucrat and advisor carried over from the era of Hafez al-Assad. A seat was made available for her at Erdoğan’s table, and she was seated there. For some reason, that scene has never left my mind. Later, during the civil war, I frequently heard her name as one of the architects of the regime’s ruthless and hardline policies, and as one of the most prominent figures of the Alawite faction.

Throughout Bashar al-Assad’s official engagements, there was not a single behavior that recalled the cruel and brutal days of his father. Alongside his wife, he had studied in Europe and consistently projected the image of a modern and civilized statesman.

He had masterfully concealed the monster within him, and no one had realized he was a cold-blooded killer. After witnessing the events of the civil war, Prime Minister Erdoğan remarked, “They used to call his father a tyrant, but this one turned out even worse.”

IN THE MIDST OF WAR SCENES

When the civil war broke out, I traveled to Syria again in 2013. From the moment I crossed the border from Turkey, it felt as though I had entered another world. That yellowish earth tone engraved in my mind dominated the entire landscape.

I was only supposed to go to Aleppo, which was 40 kilometers away, but what I experienced along the way turned a one-hour journey into a trip that lasted for hours. On the road, we were stopped at checkpoints perhaps less than ten kilometers apart. The ones stopping us were groups opposed to the Assad regime. Each group had declared an area under its control, placed a manually operated barrier at the entry and exit points, and would stop passersby to ask them questions. Some people were not allowed through, some had to pay money, and others were simply let past. Most of those manning the checkpoints were young boys, barely twenty years old. In truth, they didn’t really know who or what they were checking. If someone older gave a slight nod, they would raise the barrier without hesitation and go back to looking around with half-asleep eyes.

At one checkpoint we approached, a sudden unease spread among those around us. When I looked out the window, I saw guards dressed in black, with their faces covered, looking different from the other groups and carrying different kinds of weapons.

Without saying a word, our guides changed course and continued along a different route. When I asked, “Who are they?” they replied, “They call themselves ‘the State,’ they constantly fight with the opposition and never communicate—they’re extremely dangerous.” That was the first and last time I saw the group later known worldwide as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and we were the first to report on them at the time.

It was then that I realized the opposition was not a single unified body, but a collection of separate groups playing at mini-statehood with guns in the so-called liberated zones. I witnessed something even worse a bit further along, as we neared Aleppo. The opposition fighters shot at each other right before our eyes, and a blood-covered man walked past us, muttering to himself. While the sound of machine guns echoed, a different group that had been accompanying us sent their armed guards ahead to show us the way out of the firefight. As we followed behind a pickup truck with their guns pointed to either side, a young fighter at a checkpoint—caught up in the thrill of the fight—suddenly aimed his rifle at them. From the vehicle behind, we instinctively started shouting to stop him, because our escorts couldn’t see that he was about to fire. Thankfully, he didn’t shoot at the last moment and, after our driver shouted, realized we were not part of the clash.

That was when I understood the rumors that the opposition was killing one another were indeed true.

THE GROCER’S GUNFIGHT

In the rural outskirts of Aleppo, where Assad’s soldiers had now become visible, I think I witnessed one of the most striking scenes of this dystopian film. Just as we were entering a house where we would spend the night, we were warned: Assad’s troops had positions at the end of the street, and we needed to pass through quickly. The car would cross the street sideways and turn into the next one. I thought we’d get through it in just a few seconds, but suddenly, the loud rattle of machine guns erupted. They were firing at us—thankfully, none of the bullets hit.

I got out of the car and approached the edge of the narrow, four-way intersection, wanting to take a look down the street. Taking cover behind a wall, I peeked toward the road and saw a few small shops about four meters away. One was a grocery store, another looked like a tailor’s, and the third resembled a snack kiosk. The shop doors opened directly onto the street, and the gunfire from the end of the road was still ongoing. I could see the dust rising from the ground as bullets flew past me.

For some reason, I felt no fear or emotional shock. Perhaps it was because the people in the shops across from me were continuing with their daily work and smiling at me. Naturally, I smiled back at them—even as bullets were sweeping through the street.

Then, the man in the shop that looked like a grocery store stopped what he was doing, grabbed the Kalashnikov leaning in the corner, chambered a round, and without stepping outside, aimed to the right of the door and began firing. He was shooting at the trenches where Assad’s soldiers were positioned, but the smile on his face remained unchanged. Once his magazine emptied, he tossed a few words toward the other shopkeepers and sat back down. They were all laughing.

I think they were laughing at my astonishment over the scene I was witnessing.

Here, guns, conflict, the sound of gunfire, and bullets flying through the air were natural parts of life. Death, too, had become ordinary—almost inevitable.

“WARNING: SNIPER”

During the Bosnian War, in the besieged city of Sarajevo, every street opening toward the mountains bore a sign: “Pazite Snajper” (“Watch out, sniper”). These signs had been placed at the beginning of streets facing the hills, because Serb trenches in the mountains were killing civilians in Sarajevo below with sniper rifles. We now learn that tourists were brought in from Italy and other European countries to hunt humans—paying to kill Bosniaks here.

I saw the exact same sign—this time written in Arabic—posted at the entrance of streets in Aleppo’s opposition-held areas. Here too, people were being killed in the middle of the street by bullets whose origin was unknown. The signs were hung to warn civilians, but no one really paid attention. It seemed that, in line with the fatalistic worldview of this geography, people had come to see death as just another part of life.

The streets destroyed by barrel bombs were more striking than the scenes in Saving Private Ryan. Aleppo’s outskirts looked worse than French cities ravaged by German air raids. That familiar yellowish tone had turned into a dull concrete gray, and all color seemed to have vanished from life.

Even the faces of those living among the ruins of homes and shops, along with their clothing, were—strangely—shades of gray.

That was when I came face to face with the horrific devastation of the civil war.

A SCENE OF SHAME FOR MUSLIMS

When I visited the famous Aleppo Bazaar in 2009, before the civil war, I thought it was almost identical to the bazaars in Gaziantep, Turkey. The two cities are only 50 kilometers apart, and both bazaars date back to the Ottoman period.

When I entered the same bazaar again in 2013, during the civil war, its abandoned, bullet- and shell-riddled state etched itself into my mind like a scene from a movie. The sun was high overhead, and rays of light filtered through the holes torn in the wooden and metal canopies above the bazaar’s narrow alleys. The shutters of the shops were closed, most of them riddled with bullet holes. In areas hit by barrel bombs, there was heavy destruction, and piles of rubble had spilled into the middle of the roads. In those deserted, soulless alleyways, the haunting marks of death were everywhere.

Right next to the bazaar stood the famous Great Mosque dating back to the Umayyad era, and what I witnessed there was perhaps the most shameful scene of modern times.

The mosque’s dome had been hit by a large shell, leaving a gaping hole. Its minaret had collapsed and fallen into the rectangular courtyard. Bullet and shell marks scarred every surface, and walking through the debris was difficult. But what struck me most was the scene unfolding inside the mosque.

We entered through a large hole in the qibla wall. There, an opposition fighter had built a makeshift barricade using rubble, prayer bookstands, carpets, and books. He had extended the barrel of his long rifle through a small opening and was aiming toward the opposite side of the mosque. At the other entrance, a similar barricade had been built, manned by an Assad regime soldier. I walked bent over, trying to make sense of the scene before me inside the mosque. Sunlight streamed in through the massive hole in the dome, completing the image of two Muslim groups clashing within a mosque. At times, the sound of a gunshot echoed off the walls where “Allah” and “Muhammad” were inscribed, reverberating through the dome and out into the sky.

This may have been the most powerful scene in the entire dystopian film. I don’t think history has ever recorded anything like this—two Muslim factions, just 15–20 meters apart, barricaded behind piles of Qur’ans, bookstands, carpets, and rubble, trying to kill each other inside a mosque.

This scene of Sunni-Shiite conflict inside a mosque struck me as the most disgraceful image among Muslims I had ever witnessed.

PHOTOGRAPHS FROM A HORROR FILM

I thought what I had witnessed in Aleppo during Ramadan was enough for me to fully understand the Syrian civil war. For the last time, we broke our fast and performed the tarawih prayer in a mosque in the rural outskirts of Aleppo, then decided to head back toward Türkiye. The next morning, as we set out, I learned that the very mosque where we had prayed had been struck by a barrel bomb. Many people had been killed, and although I was deeply shaken, what I would experience afterward would affect me even more.

After returning to Türkiye, I received a call from the Prime Ministry. I was asked whether I could urgently travel to Doha, the capital of Qatar, for a highly critical and confidential news assignment. I accepted immediately and departed.

At a hotel, they brought me together with a group that included British lawyers, American forensic experts, and others whose roles I did not know. A Syrian military official with the codename “Caesar” had been responsible for photographing prisoners who were tortured to death in Syrian prisons and had managed to smuggle copies of these images abroad. A portion of these photographs would be given to CNN, The Guardian, Anadolu Agency—where I was the director general—and Türkiye Radio Television (TRT).

A forensic expert explained to us in detail that the photographs we were about to see could cause severe psychological trauma. It seemed he himself had fallen into depression while examining the images to determine their authenticity. After all media organizations signed a commitment to publish the photos simultaneously on the same day and time, I was shown some of the more than ten thousand images on a computer.

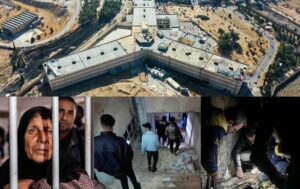

The skeletal remains of prisoners starved to death were lined up in rows in a prison courtyard. Close-up shots showed numbers written on their foreheads and chests. These were the numbers indicating that the execution order had been carried out, and it seemed they were ultimately reported to Bashar al-Assad. Some prisoners who had been strangled with construction wire still had the wire around their necks. Others had been strangled with a cable resembling a car’s timing belt, its ridged imprint clearly visible on their necks. There were bodies with gouged-out eyes, severed limbs, all wrapped in plastic bags. Dozens, even hundreds of lifeless bodies were wrapped in bags, stacked atop one another, and lined up across the large courtyard. One of the death-factory prisons was Sednaya—an institution I would later see up close.

I examined the photographs with a surprising calmness, asking questions. I later realized that this calmness was the numbness of shock.

They loaded the images onto a flash drive and handed it to me before I returned to Türkiye. Until publication time, we worked on the captions and translations of the photographs. On the designated day, at the designated hour, we published them simultaneously with the other media outlets. The impact was enormous—both in Türkiye and around the world. The United States later imposed sanctions on the Assad regime because of these images, which became known as the Caesar sanctions.

My team and I emerged from the initial shock only to fall into a deep depression. For a week, we could neither eat nor sleep. We felt ashamed of humanity itself. We could not comprehend how one human being could inflict such merciless torture upon another. I wondered what the suit-wearing, modern-looking Bashar al-Assad felt when he looked at these photos. The cold-blooded killer later dismissed them as “fake.”

Those images were the most horrifying scenes in my mental archive of Syria. I could not escape their impact for a long time. Years later, when I visited the prison where these tortures had taken place, my depression resurfaced, and again, it took a long time to recover.

THE DAYS WHEN ASSAD’S FALL SEEMED IMPOSSIBLE

What I experienced during the Syrian civil war were among the most deeply disturbing events of my professional life. We bore witness to scenes, events, massacres, torture, and exile that were hard to believe. Assad had seized full control of Aleppo and expelled hundreds of thousands of people from the city. As massive crowds of refugees ran barefoot through muddy roads toward the Turkish border to save their lives, I was on a hill in Idlib, photographing them.

After the fall of Aleppo, everyone had come to believe that Assad’s downfall was now impossible, as he had secured unwavering support from Russia and Iran. Because of this, many actors were trying to find a middle ground. Some were even working to reconcile Erdoğan and Assad—and Erdoğan had signaled openness to the idea.

But Assad was so confident in himself that he never uttered a single sentence in favor of peace. Years earlier, I had seen Bouthaina Shaaban, and now she was declaring that the Syrian army would reclaim every inch of the country, defiantly issuing threats.

The war had become frozen, the opposition had sunk into a sense of defeat, and the world had turned its gaze away from Syria. However, Israel’s assault on Gaza changed the entire region—and, in turn, altered the fate of Syria as well.

NO ONE BELIEVED DAMASCUS WOULD FALL

We were all focused on the genocide in Gaza. Suddenly, news emerged of a growing movement within Syria, centered in Idlib, and spreading outward. At first, it was seen as a localized conflict, not worth much attention. But then it became clear that this opposition offensive was expanding, advancing from Idlib toward Aleppo. Rumors began to circulate that while retaking Aleppo was a fantasy, the surrounding rural areas could fall into opposition hands.

And so began the days of revolution that would shock us all.

Türkiye was supporting this opposition group, and I was trying to gather information through my sources. We weren’t even discussing the fall of Damascus—at best, I kept asking, “Could Aleppo fall?” I was constantly told it was highly unlikely, yet the speed of developments on the ground was surprising even to those in Ankara.

And the day Aleppo fell became the day hope was kindled for Damascus. Still, the media was filled with voices insisting that it was impossible for Assad to fall or for Damascus to be taken, given the support he had from Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah—and his complete unwillingness to consider peace. But, as is often the case in this region, we were about to witness how reality could change at any moment, and how the story could suddenly take an unexpected turn.

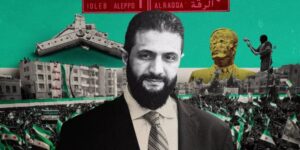

Aleppo had fallen so easily that it was only natural for the opposition to ask, “Then why not Damascus?” Everyone was talking about a commander from Idlib known as “Joulani.” It was the first time I had heard his name, and I later learned that he was someone with very close ties to Türkiye.

Two days after Joulani gave the order to march on Hama and Homs, he was heard saying, “Drop everything—we march on Damascus.”

It turns out that the times when Assad appeared strongest were, in fact, when he was rotting from within. The revolution happened so quickly that no one could believe it was real. But that’s how it is in dystopian films—scenes change rapidly, throwing the minds of the viewers into chaos.

When Joulani’s soldiers were seen in the streets of Damascus, our minds refused to accept it as reality. Only when it became clear that Assad had fled to Moscow on a Russian plane could we begin to grasp the truth of the new situation. The despair we had felt due to the tragedy in Gaza was eased, even if just a little, by the fall of the cold-blooded killer, Assad.

WHAT I SAW ON THE ROADS OF THE REVOLUTION

It was hard to believe, but Damascus was now in the hands of the opposition. I immediately set out to get there. Just like I had done during the civil war in 2013, I planned to travel by land—first to Aleppo, then to Damascus. Once I crossed the border, I saw that there were no longer any checkpoints operated by opposition groups along the roads. Much of the territory was now under Türkiye’s control.

I arrived in Idlib, now ruled by “Joulani,” whose real name is Ahmed al-Sharaa. The atmosphere was very calm, and everyone was busy with their own affairs. For nearly six years, Idlib had been a place where security had been established and Ahmed al-Sharaa held absolute authority. The revolution had been incubated in this city.

From there, I set out for Aleppo. I rode whatever transport I could find—motorcycles, minibuses, taxis—I used them all. And when I entered Aleppo, a city that had deeply moved me the first time I saw it, I noticed a cautious sense of optimism in the air. After the city had fallen, guarantees had been given that all ethnic, religious, and sectarian groups would be protected, and people had trusted in these assurances and chosen not to flee. With the retreat of Assad’s and pro-Iranian troops, order had been restored in the city, and people were celebrating in the streets. This had played a significant role in the fall of Damascus as well.

I returned to the Aleppo Bazaar I had visited during my previous trip. The market had undergone partial repairs, but the scars of war were still visible. The Great Mosque, where clashes had once taken place, had been placed under the protection of UNESCO, and restoration work had begun. However, the mosque was closed, and I wasn’t allowed to enter.

After Aleppo, I traveled toward Damascus with a group of Syrians who had fled to Türkiye and returned immediately after the revolution. Along the way, traces of the conflict between Assad’s forces and the opposition were still visible: burned military vehicles, tanks, destroyed buildings, barricades, and checkpoints… The destruction was even more apparent in Hama and Homs, as the Assad regime had established its first defensive line there to protect Damascus. But they had fled in less than two days without putting up much resistance.

THE FIRST DAYS IN DAMASCUS

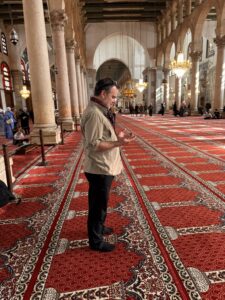

Damascus had fallen with minimal damage and almost no fighting. After “Joulani” entered the Umayyad Mosque and publicly assured the people that their lives and property would be protected, the fall of the city became even easier. The fact that nothing had happened in Aleppo served as a guarantee.

At the gates of the palace where I had once entered by invitation from Assad, now stood ragged opposition fighters, guarding it and letting no one in. When they found out I was from Türkiye, they asked to take pictures with me.

After visiting the palace, I went to Sednaya Prison. Some of the execution photos that had haunted me for days with depression had been taken there. The prison looked terrifying. As soon as the revolution began, a raid was carried out to rescue the inmates, and what was discovered seemed like more scenes from a dystopian film. There were people who had not seen the light of day for 40 years, those who still believed Hafez al-Assad was alive, paraplegics, and others who had lost their minds due to torture. The people who raided the prison recorded videos of these survivors and shared them with the world. The smell of burning and decomposing bodies hung in the air. It became clear that Assad’s regime of oppression had done even more horrific things to the Syrian people than anyone had imagined. I wanted to leave immediately because I could feel the depression I had previously experienced being triggered again.

A short distance from the prison, people were digging strangely in an open field. When we arrived, we learned it was a mass grave where prisoners who had died in the prison had been secretly buried. The corpses I had seen in the photos—wrapped in plastic, with numbers written on their foreheads and chests—had been buried here. Mass graves began to emerge in many parts of the country. But the horrifying image of the prison stayed in our minds for a long time. Executions had continued there even after the revolution had started. All of this had been carried out under the orders of the cold-blooded killer, Assad.

MY FIRST INTERVIEW WITH AHMAD AL-SHARAA

There were celebrations all over Damascus, but the largest crowd had gathered at the historic Umayyad Mosque. I went there for the first Friday prayer, joining the incredible throng of people. Everyone was chanting slogans, embracing one another, and expressing their joy. Ahmad al-Sharaa’s soldiers were maintaining security, and people were constantly lining up to take photos with them. Many civilians carried Kalashnikov rifles, clinging to the habit of never putting down their weapons.

People were handing out sweets, offering dates, and street vendors had turned the area into a scene of festivity. The most-sold item was the three-star Syrian flag. Young and old alike were buying these flags and waving them with pride. I was witnessing the joy of a people in the early days of a revolution.

A few hours after I left, a rumor began circulating: the head of Türkiye’s National Intelligence Organization (MİT), İbrahim Kalın, had arrived in Damascus. At first, we couldn’t believe it, but after investigating, we learned it was true. Photos of İbrahim Kalın and Ahmad al-Sharaa at the Umayyad Mosque were published—and they sent shockwaves across the world. It was now clear which country had stood behind the revolution.

My journey through Syria continued like a scene from a dystopian film. I learned that Kalın and al-Sharaa would be visiting a location nearby, so I went there and waited for three hours. When I was told, “They won’t be coming,” I decided to leave—only to see the guards suddenly spring into motion. I waited another hour, and then a large convoy suddenly arrived. In the driver’s seat of a black Mercedes was a bearded man, and next to him sat MİT Chief İbrahim Kalın. I couldn’t believe my eyes—but in this dystopian tale, there were no more scenes that could be called “unbelievable.” Anything could change at any moment, and a new story could begin here.

Both men were now standing in front of me, and İbrahim Kalın introduced me to Ahmad al-Sharaa, the leader of the revolution. The man whom every journalist in the world was chasing, for whom even a single photo was worth any sacrifice, hugged me and said, “Welcome.”

Then they allowed me to ask a few questions and take two photos. I became the second journalist in the world—after CNN—to conduct an interview and take photographs of him. In Türkiye, I had the honor of being the first.

He appeared young, calm, and impressive. Surprisingly, there was no visible shock on his face from having suddenly become the sole ruler of Damascus and leader of the revolution. But as we spoke, I realized that even he had not expected to take Damascus so easily.

Just four days after the revolution, I had taken a photo with Ahmad al-Sharaa and the MİT Chief in Damascus—and with that, the scenes of the dystopian film felt complete. I returned to Türkiye. But even a year after the revolution, I see that this incredible story is still unfolding.