Professor Erol Göka: Türkiye is the Flower Field of Our Hope for the Civilization of Compassion

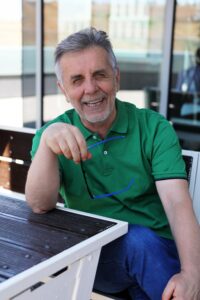

Dr. Erol Göka*, one of the most respected organic intellectuals of our country, is recognized not only in the field of Psychiatry, his professional domain, but also for his interest in the fundamental problems of humanity and society, as well as his original ideas. Dr. Göka has produced numerous original works spanning areas such as existential psychology, social theories, and political thought. He offers, so to speak, a profound intellectual journey by synthesizing the soul of this nation with the challenges of the modern world, all grounded in our own beliefs and values.

Kritik Bakış

…………………

-In a comprehensive conversation with Dr. Göka, we explored a wide range of ideas concerning humanity, civilization, spirituality, our nation, and its future. We now present this enriching dialogue for your consideration.

Mr. Göka, in your book “Goodbye (Hoşça kal)” you deal with death and mortality; in “Does Life Have Meaning? (Hayatın Anlamı Var?)” you deal with meaning, meaninglessness and freedom; and in “Loneliness and Hope (Yalnızlık ve Umut)” you deal with the ultimate loneliness, alienation, hope and the ranges to which one must turn. You discuss the main themes on which the existentialist approach in the West is based. In your book From the Heart/Our Center of Existence, The Heart and its fundamental action (Kalpten/Varoluş merkezimiz Kalp ve temel eylemi merhamet), compassion, you focus on the concept of ‘heart‘, which is not included in western thought. You interpret emotions and virtues such as reason, justice, mercy, goodness, love and compassion through the heart. What was the reason for this heart-centered approach? Why were existentialist philosophies and even modern thought in general disconnected from what you mean by the heart?

First of all, I should point out that many of the themes examined in my work, which you have summarized very well, are in fact frequently taken up by existentialist philosophy and psychology. Yes, I consider myself to be closest to existentialism among Western thought(philosophy and psychology), and I even consider existentialism and ecological approaches to be the most sincere opposition to the negative developments that have emerged in the West throughout modernity. However, I must emphasize two points. First, what exists between us and existentialism is only an affinity. This affinity does not mean that I sign everything they say, and there are more differences than similarities between us and atheist existentialism, especially the one centered around the name of Jean Paul Sartre. But I do think that the concepts and ideas that existentialists have developed about what distinguishes human beings from other beings and the universal existential problems of being human are really seminal, and that we can better express ourselves and ourselves to Westerners. Secondly, as a Muslim, of course my own faith and ideas are sufficient for me. After all, I do not define myself as an “existentialist Muslim” but only as a “Muslim”, and I say that existentialism is the only school of western thought, philosophical and psychological approaches that I feel close to.

As such, I inevitably come to the conclusion that I have the idea that my position, which stems from living in a Muslim culture and my mind functioning accordingly, gives me an advantage. I say to the existentialists, “You make acceptable observations about human beings and life, your criticisms of the modern mind and psychology are appropriate, but all these are incomplete by their very nature. If you really have a sincere view of human existence, you should also listen to explanations of human existence from other cultures. For example, in theMuslim cultural circle, themes such as death, freedom, loneliness, meaninglessness, which you have mentioned, have a framework and life that can be understood in a more robust and comprehensive way than your ideas, and there are concepts such as “heart” and “worship” that you have become strangers to. You should research these in order to expand the scopeand depth of existentialism.” For a long time, while I have been explaining existentialism toour own intellectuals with the subjects I have been dealing with in my works, I have been trying to talk to Western existentialists and tell them these things. In my book ‘PsychologyExistence Spirituality (Psikoloji Varoluş Maneviyat)’, I was trying to concretize what I said in terms of my own profession.

One of the shortcomings of Western existentialists is that their criticism is limited to modernity, and the perspective and concepts of the traditional people of the world do not enter their agenda. It is true that some of them are trying to overcome this, but they are more attentive to the voices coming from Hinduism, Buddhism and other areas that can be easily articulated with secularism. The attitude of Western academia and the world of thought to ignore the Muslim world continues with them. However, in my opinion, Muslim scholars represent the perspective of the traditional world in the most authentic way, moreover, they never give up interaction with ancient thought, especially Ancient Greece, and they do not ignore them.

The concepts of “heart (kalp)” and “reasoning with the heart (kalp ile akletmek)” are key to articulating all this. Some argue that the mention of the heart in the traditional world and in the Holy Qur’an was a simple medical error that has been corrected by advances in modern science. They think that the people of the ancient world did not know that the brain is the organ of thought, that they spoke ignorantly and attributed untoward qualities to the heart. Of course, thanks to modern science and medicine, we know much better the functions of the human brain and the workings of the heart, an organ of the circulatory system. What we didn’t know, and what we were unnecessarily superior to, was that the paradigm in the traditional world was completely different from modern times, and that the issue of how best to live as a virtuous person in this mortal world, which we moderns don’t think much about, was decisive for them. They continued the discussion of reason(akıl) accordingly. They never thought of our brain as a useless mushy formation inside our skull, they were aware of the contributions of the human brain to us, but they were more concerned with morality and virtues. They thought that the search for truth (epistemology), ethics and aesthetics were what made human beings human, that these characteristics could not be revealed through brain research because they were given, ontological characteristics, and to express them, they talked about a spiritual heart (manevi kalp) other than the organ inside our rib cage.

In my work, I try to explain that we have no objection to the knowledge produced by the modern perspective, but that we need a filter to eliminate the destructive features of this knowledge for human beings and humanity. I try to show that this filter is what the ancient scalled “the heart”, and I try to tell the existentialists that if you do not understand the heart, what you say will be null and void and will not find a ground.

-Just as it is argued that other virtues are actually rooted in compassion, love and affection can very well be considered as derivatives of compassion. You say that thanks to the heart and its fundamental act of compassion, there may be a possibility for a healthy and solid relationship between psychological sciences and theology, whose juxtaposition is feared like the bogeyman. Why is this connection important? In general, do you believe that the ancient debate between science and religion, philosophy and theology can be brought to a healthy composition?

-Yes, one of the things I realized during my studies and reflections on the heart was that the most important function of the heart is compassion, and that compassion is at the basis of all other virtues. I discussed this at length in the book “From the Heart (Kalpten)” As for your question. Of course, I believe that it is possible to build strong bridges between science and religion, theology and philosophy, without identifying them with each other, without denying each other. No, I don’t mean to put forward theses such as “this scientific research has confirmed what is claimed in this verse in the holy book”, in fact, I think the opposite, that science and religion should not enter into each other’s fields.

When I talk about the bridges between science and religion, philosophy and theology, I worry about things like this: Those who see the damage that modernity, modern science and technology, along with its many undisputed benefits, has done to the human world of meaning, to the quality of life and to the relationship with nature, rightly object, but unjustly want to erase scientific endeavors in a totalitarian way. However, science, as the human endeavor to reveal the material connections of the relationships and workings between things and to enrich the world of life with a technique developed on the basis of this knowledge, never contradicts religion. Rather, the scientist works by focusing his attention on answering the question “how”. However, the dazzling achievements of modern science have unfortunately led to the understanding that the search for truth, ethical and aesthetic values should be conducted entirely through science. Science abandoned the “how” and started trying to answer the “why”, first trying to render religion and theology, and then philosophy useless. These were quite unnecessary attempts, which would have no result except to colorize, grayize and render meaningless history and humanity…

The production of science under the conditions of capitalism has led to an unquestionable, unbridled technology that has created handicaps that are not visible at first glance. We now think about how we should live and the “good life” according to the results of capitalist competition, and we think we have solved the problem accordingly. All of this makes the discussion of democracy and freedoms in the political sphere futile. Because the political sphere has already turned into a simple legitimization field of capitalist competition and technological reason, but the insiders, the political professionals, are not even aware of this.

As a result, we need a critique of science, a debate on the limits of science. Only philosophy and theology, which are the true owners of the question “why”, can fulfill this need. The world of science should give up the futile attempt to produce value from science, and just as it does not try to replace art, law and politics in life (I hope so), it should make room for philosophy and theology in academia and in the world of thought, and acknowledge and appreciate their existence.

-The concept of reason is another topic of discussion. ‘In the traditional world, the distinction between the thinking involved in reasoning, making causal connections, and conducting transactions, and the thinking (reason) involved in moral decision-making has always been maintained. In particular, it was believed that moral reasoning and judgment was done by the heart, not the brain.’ On the other hand, the Qur’anic concept of “heart (kalp)”- reasoning with the heart (kalp ile akletmek) – has a much deeper, encompassing and clearer meaning than “logos”, which includes “pathos” and“ethos”. What about the claim that modern science has progressed and developed on the basis of this brain-centered definition of the biological mind rather than the heart, and that the traditional rational heart is an assumption of moral judgment rather than a scientific one?

-This is the main claim of “From the Heart (Kalpten)”, as I tried to explain in your first question. That the epistemological, ethical and aesthetic aspects that make human beings human are ontological, that is, they are inherent to human nature and can never be completely consumed by modern scientific research. Human beings, by their very nature, pursue the truth, inevitably make moral judgments in every decision and seek the beautiful. “To the good, to the beautiful, to the true” is the motto that has guided us throughout human history, except in recent times. When we put the brain and matter at the basis of our perspective with a crude scientistic and materialistic reductionist understanding, we have moved away from understanding human beings, the world and life; we have sacrificed all the subtle and beautiful aspects of human beings and life to technology. We have never understood that the rational heart is actually the inner voice that constantly tells us to “put every thought and action of yours through a spiritual filter, see if it will serve humanity and nature, the beautiful and the good, that is, if it is moral”. We could not comprehend that the main task of the spiritual heart (manevi kalp) is moral judgment, or rather the constant introspection of whether our decisions are moral or not. “How naive these ancient people were, they thought the heart was the organ of thought, haa haa haa haa,” we laughed. Our modern delusions did not allow us to think for a moment why the ancient scholars divided the mind into many types.

-While criticizing İbrahim Kalın’s approach in his book Akıl ve Erdem (Reason andVirtue), which sees reason as “a touchstone that stands in the middle”, ‘Kalın calls things that are in accordance with reason “reasonable” and those that are against it “irrational”. According to him, some things are above and beyond reason, i.e. “supra-rational”, while other things are below reason, i.e. “sub-rational”. This classification is highly problematic and seems to be heavily influenced by modern intellectualism. In myopinion, Kalın’s assigning the intellect the task of controlling emotions stems from this problematic classification.’ You say. Could you elaborate on this criticism? What is your approach to the relationship between reason and emotions and the classification of the irrational?

-First of all, let me acknowledge a right. İbrahim Kalın’s efforts and my efforts are almost completely parallel and directed towards the same goal. The criticism I have mentioned and will continue here does not pertain to the essence and is incidental.

I have always objected to putting emotions in front of the mind and in the lower layers of brain functioning, partly because I live in the field professionally and closely follow neuroscience research on the interactions between emotion and thought. This was one of the conclusions of evolutionary brain research at the turn of the century. The findings in the world of science that the frontal and upper parts of the brain are thought to be involved in the production of ideas, while the lower and middle parts of the brain are thought to be involvedin the emotional domain have had many intellectual repercussions in the world of thought. Today, we know much better that thought processes are not independent of emotions and that these issues are much more complex than we think… We are not in a position to distinguish whether reason controls emotions or emotions control reason…

For my part, I have many objections to the methods and concepts used in brain research. The areas where brain research has not even begun to crawl are the search for truth, ethics and aesthetics. Likewise, the connections between emotions and thoughts, love relationships are far, far away from answering our questions. We still don’t know why we sleep, why we dream, why we love. Words and concepts, that is, the human ability to symbolize, have not yet been discussed in the academy, except for the faintest of breezes. It is so chaotic and bloody that I have not been able to start writing my last book “Self Consciousness Will(Benlik Bilinç İrade)” for a year. The main thing that stops me is trying to distinguish what is useful among so much information; I can’t find time to write because I am sorting…

When those of us who are professionally involved cannot even manage to stutter, let alone speak, ideas about what is in and what is out of the mind are a bit far-fetched. By the way, let me mention my main fear. While those who take it seriously are hesitant enough to refrain from even uttering a sentence about the self, consciousness and will, unfortunately the hegemony of technological reason is all around us. Just as the advances in digital technology and the devices we have added to our daily lives have created generations who do not know the difference between virtual and real communication, I fear that soon artificial intelligence, the mind itself, robots will begin to settle in our minds and lives as superhuman beings, let alone human beings. We will shout from afar: “But we haven’t even finished discussing what reason is”

-The relationship between reason, morality and politics is another important topic of discussion. At this point, you make important emphasis on the contradiction of modern thought, which feeds on the distinction between the moral good and the political good and leads to both moral and rational inconsistency. ”In my opinion, due to the disconnection between morality and politics, it was inevitable that Carl Schmitt would produce his political philosophy as a Nazi jurist, and that Levinas, known as the philosopher of the ‘other‘, would ultimately become a partner in the persecution policies of the Jews. However, what is moral is what is just and is rooted in the sense of justice within us. To be just is not a simple, quantitative attitude, but to live in a constant existential tension.’ You say. Let us come to the concept of justice. On what basis do you establish the relationship between justice and reason and morality? In other words, what is your solution to this most fundamental problem of politics?

-Especially with the Gaza genocide, this question becomes very important when we see that everything, even all kinds of cruelty, is legitimized in front of the eyes of the whole world with an understanding of law.

Without the notions of right, law and justice, there can be no human relations and social life. In fact, some thinkers say that justice is present in every society to one degree or another, otherwise no collective function can be fulfilled. They are not wrong. Every value requires justice; every society demands it. Without justice, there can be neither legitimacy nor illegitimacy. Moreover, where there is no justice, oppression immediately arises. It is contrary to human honor and dignity and impossible to survive with ultimate oppression.

Without dwelling on the moral and psychological dimensions of the concept of justice, without illuminating the place of justice as a virtue in our psychology, we cannot understand justice and its summit, “equity”, and we cannot arrive at the essence of Aristotle’s statement that “equity is not what is right according to the law, but the regulator of legal justice”. “When the just cannot be made strong, the strong is made right”; ‘interest must be subjugated to justice, not justice to interest’ do not make sense to us. When we do not understand the essence of the matter, when we limit justice to legality and equality before the law, it is not possible to talk about what will happen if the laws are not fair, what will be done, how our psychology will react. For all this, we need to think along the high tension line between morality and psychology. We need to think about justice not only as a legal and social necessity, but also as a virtue that is embedded in our psychology.

A judgment, a behavior may be politically correct, legally legitimate, but it may not be morally appropriate; it may not pass the scales of the scale of justice within us. In order for the political to be truly right and the legal to be truly legitimate, we need the approval of morality. If we do not want to reduce politics and law to a mere technique, we have to comprehend them in a way that our hearts will be satisfied. Expressions such as “the scales of justice within us” and “hearts being satisfied” are very foreign to modern man… Either we don’t mention these concepts at all, or we embrace them fully and criticize modernity. My preference is of course the latter…

In ancient Greece, the question “What is the ultimate goal of moral behavior?” is usually answered with “Happiness, which is the highest good in itself”. Happiness as the highest good has nothing to do with “pleasure” and “enjoyment”, as many now confuse them. Happiness is discussed in relation to virtues. For example, according to Plato, human beings have three faculties, namely “reason, anger and lust” and a virtue corresponding to each faculty. The virtue of reason is knowledge, the virtue of anger is valor, and the virtue of lust is chastity… Another fundamental virtue that emerges from the reconciliation and cohesion of these three virtues is justice… “Justice is not a virtue like the other virtues. Justice is the horizon of all of them and the law of their coexistence…” Plato thinks that happiness comes from acting in accordance with justice and righteousness, and that unhappiness stems from immoderation and injustice. It is impossible for happiness to emerge from pleasures, possessions, fame andpower… In short, “justice is not a substitute for happiness, but there is no happiness exempt from justice.”

Muslim thinkers such as Farabi, Ibn Miskawayh, Ibn Sina, Ibn Hazm, Ragıp al-Isfehani and Imam al-Ghazali continued the understanding of happiness based on the virtue of ancientGreek philosophers and sacred texts. Unlike both their predecessors and later Westerners who continued in the same vein, they also believed that true happiness is not worldly but ethereal, and that the greatest happiness (seadet al-guswa) is found in the good life in the hereafter.

You will say that you can’t explain all this to today’s people who don’t care about happinessexcept “enjoying everything as much as possible” and “taking care of themselves”. You are right, but let’s go on anyway, because I cannot answer your questions from the perspective of today’s people…

In other words, justice is both fundamental and a virtue that is very difficult to define on it sown, but which emerges in harmony with and alongside the other virtues… If we identify these four fundamental virtues, namely knowledge, valor, chastity and justice, as the main choreographers of the human conscience, and if we take into account that it is through conscience that we rise from being human beings to humanity, we can conclude that, one way or another, the sense of justice is anchored in our existence. Not only is the sense of justice anchored in our very existence, but it also regulates all our behavior.

If our judgment and action is not morally appropriate, even if it is economically in our interest, politically vote-getting, legally legitimate, or if a rigid moralism breaks our integrity with other areas, the sense of justice within us immediately kicks in. And it is precisely on the sense of justice that virtues reside in our inner world. The scale, the epitome of justice, is essentially in our inner world. When the scales are out of whack, when the balance is out of whack, that is, when we are not being fair, the seismograph of the scale of justice within us registers. Our conscience starts to ache. After unfair trials, it is these recordings and pains of our conscience that make us say that this should not be all there is, that make us sure of theexistence of “divine justice”.

This is what we are saying, “What is justice? Putting something in its rightful place. What is oppression? Putting it where it does not deserve to be…” Mavlana Jalaleddin’s statement may bring some clarity. “It is not justice that makes the just just, it is the just who do justice; justice is valuable as long as there are just people to defend it” becomes more understandable and realistic for us. We realize that justice is ultimately the work of virtuous people. And, of course, that our only duty for true justice is to raise virtuous people… Politics, which does not deviate from morality, must focus primarily on this duty and set an example for new generations in every attitude. If it does not do so, if it breaks the scales of justice, if it focuseson winning and showing power, it has no relation with morality from the very beginning.

-‘There are Western thinkers who care about compassion, who realize its difference frompity, who see it as an important virtue, but even the most humanistic and libertarianEnlightenment philosophers do not include people living outside the West in their words.’ You say. The barbarian-backward-primitive characterizations of non-Western humanity by the founding figures of Western Enlightenment thought such as J. Locke, D. Hume and A. Tocqueville are still the basis of political and ideological Orientalism, which is the product of the same root view. Do you believe that this western arrogance can be cured with compassion? Can compassion, mercy, the rational heart hold a mirror to the refined barbarism that westerners project backwards?

-Western thinkers are indeed very confused about compassion, they have written so muchabout the differences between pity (commiseratio), compassion (misericordia) and mercy(compassion) that it seems strange to us… Of course, there are those like Schopenhauer whosee compassion as the root of morality, its most competent and moving force; and those likeHannah Arendt who try to separate compassion from it in order to speak against the Western corpus that views “pity” negatively.

Andre-Comte Sponville, a contemporary French thinker and author of the “Treatise of theGreat Virtues (Büyük Erdemler Risalesi)”, agrees with Arendt and draws attention to the arrogance and self-righteousness of the person who feels pity. “Mercy is what allows us to move from one to the other, from the emotional to the ethical level, from what is felt to what is desired, from what is to be to what ought to be… Mercy is the only virtue that opens us not only to all humanity, but to all living beings, or at least to those who suffer. Wisdom based on and nourished by compassion is the most universal and the most necessary of wisdoms.” Sponville likens compassion to love in this respect, but he prefers compassion over love, Buddhism over Christianity. “Who can be sure that he has witnessed true human love? Andwho can doubt that he has witnessed mercy?. Jesus‘ message of love is more uplifting, but Buddha’s lesson of compassion is more realistic. ‘Love and then do whatever you want’- or show compassion and do what you have to do,” he says.

In “From the Heart (Kalpten)”, I have explained at length the importance of the concept of compassion in Muslim culture, starting with the Basmala(Besmele). However, our intellectuals are not fully aware of this. The approaches to compassion and love in the Muslim world and in Western culture are quite different, yet not even a doctoral study has been conducted on these issues. Likewise, it is surprising and sad that those who have taken a stand on the concept of “universal love”, which is the main theme in Western culture andChristianity, and who have correctly identified the basic position of compassion among the virtues, probably do not know Islam or know it incorrectly, and their sympathies are directed towards Buddhism. In this situation, it seems unlikely that westerners will be able to comprehend the concepts of compassion and the heart and experience an intellectual enlightenment. I have no such hope either. But let’s talk about this parenthesis that I will open if the opportunity arises. After the Gaza genocide, there are incredible transformations in theWestern conscience, there is no possibility of intellectual enlightenment, but I think there may well be a practical conscientious realization. Because compassion and the rational heart continue to exist and function for every human being whose hearts are not sealed…

-“Yet, despite the difficulties, reconciliation is not impossible. The Islamic world can walk without blaming all its problems on the West and without falling into the trap of occidentalism against orientalism. “An Islam-West debate free of Eurocentric thought patterns and liberal-secular prejudices can contribute to the development of deeper and more stimulating perspectives on modernity, reason, the individual, freedom and tradition.” You say. Is this really possible after Gaza?

-I see myself as a “soldier of hope.” I don’t know if it comes from being a physician, but my job is to look for solutions, to try to open every door of possibility I can find to make room for hope in this terrible world. As a former Marxist and as a Muslim, my mind has always worked with the hope of a universal salvation. I have a mind-set that predisposes me to think about human history and achievements, as well as sedition and mischief, for all humanity, east and west. After the Gaza genocide, my hope for the west and the east to walk together did not diminish, on the contrary, it increased. Let me try to explain:

Yes, we are experiencing a great change and transformation. In fact, I think that after the Gaza genocide and resistance of October 2023, a new milestone has emerged and that from now on, at least the last period of modern history should be called “before Gaza- after Gaza”.

Let us first try to visualize what happened in the last century before this point was reached: For 70 years, we have been immersed in hundreds of Holocaust movies, novels and ideas. Especially in the post-2000 period, we have fallen into a conjuncture in which bans on the grounds of anti-Semitism have increased and the Zionist-Evangelical partnership has presented the apocalypse as something to be expected and even forced.

The Jewish-Christian tension, which for hundreds of years was the West’s greatest humancontradiction, was left in the lap of the Islamic world after the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel after World War II. This transfer of the Jewish question was a strange form of solution that left the Western world with mixed feelings. In fact, they were pretending, they knew themselves that it was only a postponement and not a real solution. But their psychology made the choice a little easier, especially after the relative disappearance of the Iron Curtain and the great Russian threat that was coming at them like an avalanche from the north, and they invented the concept of “Islamic terrorism” to fill the vacuum. There wasno longer the hope of communism; they realized that they had to find a new “other”, and that was Islam and Muslims. Therefore, after the end of the bipolar world, they began to embrace the Zionist theses and the state of Israel, which they had at first reluctantly put into practice with some reluctance, with more enthusiasm. In a sharp turn, they began to love their sworn enemies, the Jews and Israel, more and more enthusiastically. They canceled the irirreconcilable theopolitical contradictions and turned the eternal Jewish-Christian contradiction into a “Jewish-Muslim tension”. They set out to watch what would happen.

They just watched, and as they watched, Israel expanded its borders, increased its population and its massacres. There was the Bosnian Genocide in the heart of Europe. The Middle East turned into a bloodbath, the Mediterranean was filled with the corpses of poor refugees, and they continued to look on as if nothing had happened, as if they had nothing to do with it all. From time to time, the consciences of Catholics and Orthodox, in particular, seemed to be unable to bear it all, but discourses depicting Muslims as “horrible creatures” emerged, and they continued to turn their fears into antagonism and hatred, citing so-called “Islamic” formations as justification. Racism and xenophobia have been on the rise. So much so that Stjepan Mestrovic completely gave up on modern western people, whom his teacher David Riesman, the author of “The Lonely Crowd”, lamented as “the extroverted type”, after looking at their lack of reaction to the Bosnian genocide; he called them a “transsentient society”, almost pushing them out of human behavior.

Everything was taking place on such a socio psychological ground, accompanied by the progress of what I call “technomediatics”, a process that works against ontology and in favor of technology, supposedly against humanity and virtue in the name of serving human interests and pleasure.

The family, society, art and even our biological structure, which forms the basis of our identity by making us men and women, were being dissolved piece by piece. As the moral ground shifted beneath our feet, the minimum commons that united us as human beings lost their meaning. Whatever we call “Scandal!”, “Disgrace, no way!” and whatever brings us closer to each other, or rather to humanity when we see such situations, whatever reminds us of the truth of being human was evaporating, and everything solid was evaporating as long as we remained scandal-free. The academy was declaring that we had entered the “post-human” era. We were asked to forget everything we knew about human beings and society and to rethink and rebuild everything according to the demands of the technomediatic world.

It was in such a world that the Gaza genocide took place, and even if we cannot say that humanity stood up against the demands and compulsions of the pro-genocide states and rulers, it gave a strong voice. We knew that human beings have a very volatile structure that fluctuates between the heavens and the bottom of the earth, but they could not succeed in changing the triangulation point, the touchstone, the keystone where all existential anchors converge. This point in question is morality, on which the ontology of man is based. The center of morality is referred to as the “heart” in all traditions throughout human history. When morality disappears completely, human beings will truly perish, and this is impossible because it requires that all hearts be sealed and blackened.

With the Gaza genocide, the truth that we must hope for all those who have hearts, whose hearts have not yet been blackened and sealed, has once again become clear. Man was ultimately an ontologically moral being because of his “spiritual heart”. Just as our material heart produces blood, the spiritual heart, which makes it possible for us to remain human and make human relations possible by constantly producing compassion, would one day rebel, our tolerance for moral decay and degeneration would reach its limit.

After the globalization of the banality of evil while genocide is taking place in Gaza, conscience is also globalizing; a revolutionary situation is emerging that will change the entire system. We understand from the tremendous reactions of Western people, whom we called soulless and emotionless only yesterday, to the Gaza genocide that Western societies have shrunk from anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, racism, xenophobia and technology-centered politics and want to return to a human and morality-centered worldview.

Of course, my heart and my observations, what I want to happen and what I think will happen are intertwined in these words. Tomorrow I may turn out to be completely wrong, but as a soldier of hope, I will never stop thinking that Gaza is a new milestone…

-You say that in the technomediatic world, individuals are looking for a security to be tied to and that paranoid overlords respond to this modern need. In a world where the masses are constantly manipulated by technomediatic indoctrination on the one hand and paranoid overlords on the other, do you think it is possible to return to the ancient, the natural, the traditional values and ties, or for the authentic to rise from the ashes?What is it that binds human to human anymore? Do you believe that humanity will desire the good, the beautiful and the true, the genuine mind, compassion, justice as much as it desires a new house, car, cell phone or a comfortable, fun and sensual life?

-Yes, without a doubt, absolutely! Because I trust in our hearts and in the One who fills it with mercy…

-You give a special place to Islam as a need for existence and resurrection, or rather toIslamic values as a dynamic of civilization, culture and spiritual liberation. ‘Islam is the last bastion of resistance against the complete commodification of the South’s existence by the wind of extreme secularism and anti-religious sentiment blowing from theNorth… In addition to its commonalities with other monotheistic religions and its past contribution to what we call universal civilization, we have to give justice to Islam’s intrinsic value, preserve it and bring it back to life. Islam is an atypical partner, able to question certainties and contribute its own stones to the building of a new universality that is still being constructed… Our point of departure, our common denominator, is ‘reasoning with a reasonable mind (makul bir akıl ile akletmek )‘, which is mentioned in more than forty-five places in the Qur’an.”

So, how is this going to happen? Who will do it? On a more concrete level, in which conceptual framework and with which dynamics can one contribute to the building of universality that is still being constructed today?

-The questions and answers have been lined up in such a succession that someone who does not know me might think that they are dealing with an ideologue who sees the religious perspective as a panacea for all kinds of problems. Of course I am not. Just as my view of the human individual is close to existentialism in the West, my view of social values and politics is close to conservative thought in the West. I do not believe that we are given a simple prescription for salvation like a pill or a prescription. I think that world life is both a world of test and a teacher, that the purpose of life is to mature the soul, that the dialectic of meaning and interpretation keeps changing on the condition that the fundamentals are preserved, that the values adopted by society should be taken into account, and that we should work in a reasonable line, a middle way, without opposing science and religion, reason and faith. My emphasis on Islam is because I grew up in the Islamic cultural basin, because I believe that as a religion it is the most suitable spiritual system for life and human beings, and yes, today it is the last bastion, the last stronghold against the ravages of modernity. Well, in the face of the seide as of mine, he can start listing the negativities about the current state of the so-calledIslamic world. We can sit down and talk.

I would also like to say this. The masters of our profession, whom I look up to the most, know that in the end we are doing a practical work, not a theoretical one, and they think “such and such a person has such and such a problem, what should we do to solve it?” without involving the theory much, almost suspending their theoretical knowledge. I tend to think like that. We live in a world full of problems and troubles, and even the most basic concepts such as spirituality and humanity have started to take on completely different meanings than they have taken on throughout history, technology has overtaken ontology, and human beings have started to dehumanize. There are libraries of works on the causes and solutions to this situation. They are there, but the question remains before us: “As humanity, as Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, Deists, atheists, Easterners, Westerners, people and societies with tens of different mother tongues and ethnicities, what should we do in such a world?” I don’t think the answer to this question is as simple and easy as saying, ‘Join our religion and be saved!’ I think that every culture of life should find points of resistance again stop pression and anti-humanity, and move forward in solidarity.

What we should also do as Muslims is of course another sub-topic… I recently tried to answer this question with the article “Thinking while the concepts of human and spirituality change content (İnsan ve maneviyat kavramları içerik değiştirirken düşünmek)” in Tezkire magazine. This article, which is also available on my website (www.erolgoka.net), ended with the following suggestions:

1. In its pursuit of knowledge, modernity has forgotten the basic structure of the universe, life and human beings. It has accumulated a lot of information, technologized it, and made life so complex that it has made wisdom impossible. In such a chaos, it is very, very difficult to find out what is authentic and true, and to understand the Sacred correctly. Therefore, the steps to be taken should take into account that the structure of spirituality, which was almost identical to religion in the traditional world, has changed a lot, and that every human being has a spiritual sphere that directs and gives meaning to his or her life, and that this sphere is constantly blended with science-philosophy-traditional religions and eastern beliefs.

2. The dignity (mükerremlik) and irreducible ontology of the human being must form the basis of a spiritual objection to the world in which we live, and attempts to eradicate human dignity and honor must be strongly opposed.

3. One aspect of the dignity and irreducible ontology of human beings is the ability to view nature and the universe with the same perspective. “Every Adam is a universe”, every human being is a reduced image of the universe. In other words, it is necessary to be able to maintain the perspective of “man is a small universe, the universe is a big man”. For this, it is necessary to recognize the benefits of science and technology, but at the same time to stand against the destruction of ontology by technology.

4. It is necessary to revive the main concepts of the traditional world, such as “heart” and“reasoning with the heart”, which have been devalued as unscientific. It is necessary to take as a motto that morality and virtues, goodness, compassion and hope, which form the basis of traditional human relations and whose importance in the formation and functioning of societies has been denied, are not historical but universal-ontological truths, which have been reduced to an academic field, ethics.

5. Insist that human beings are ultimately “transcendental” and “believing beings” (homo religiosus) and resist the opposition between science and religion.

6. It should be realized that religion is for human beings, that every human being can become human through faith, and all human beings should be approached with this awareness and tolerance as much as possible.

-In this context, how can the Islamic world find a way out between a religious fanaticism identified with DAESH and Islamophobia under the pretext of this so-called fanaticism? You emphasize the concepts of democracy, the rule of law, the rational heart, political morality and justice, and you say that there is indeed hope and possibility for a new good-good-correct art and aesthetic results that these will produce. You define this as a civilization of compassion. So is this a possible goal, an imaginary metaphysical idea? And where do you think Turkey, in the sense that you say “Turkey exists”, is in this goal, in this idea?

-We need an intellectual output or outputs that radically confronts DAESH and any fanatical understanding of religion that is positioned against Muslim moderation, against the ambiguity that says “Allah knows best”, that rejects the paranoid overlords in the religious field, and that defends the average person’s view of religion. We need tens and hundreds of Taha Abdurrahmans. We need an understanding that does not fear diversity, on the contrary, sees it as a richness…

“Compassion is not born from hardness of heart, from hard hearts. Mercy is the softening of the heart, the removal of the black seal from the heart. Compassion arises from faith, from breaking one’s own idol and all idols in the heart first. Mercy extends a helping hand not to the souls, but to the opening of the souls. Undoubtedly, the souls are also shown mercy in order to harbor those souls. Mercy is the yield of pure intentions. Any act that carries hypocrisy and ulterior motives cannot be included in the repertoire of mercy. No one should think that others are in need of his mercy. On the contrary, we are all in need of mercy, the spirit of mercy…” I think we need a civilization of compassion in order to implement such an understanding of compassion expressed in these words of Sezai Karakoç. For this, we need civilization politics that emphasizes need against consumption, moderation against extremes, human and justice against power, and politicians who will do politics with such an understanding…

I thought I shouldn’t say it, I shouldn’t act on suspicion, but let me say it. The civilization of compassion, the politics of civilization, and the people who will implement this politics can only come from Turkey. For me, Turkey is not only my homeland, but also the flower field of my hope, where a thousand and one seeds have been sprinkled on the soil for a thous and years.

-Finally, let’s come to the most basic and widespread problem related to your professional field, but actually to human beings; fear of death, anxieties, loneliness, meaninglessness, neurotic personalities, schizophrenia, sociopathy, addictions, identity crises and conflicts, group rage, tendency to violence… We are faced with many more individual and social problems. There are serious problems in terms of urbanization and, more generally, nationalization, and raising personalities instead of selfish individualism. In this sense, what would you suggest for both individual and social healing? What kind of treatment would you recommend as a physician and as a munawwar against the destruction of a diseased sociality that is gradually decaying and deforming politics?

-I have just mentioned the name of a Moroccan intellectual, and I stated that there should be many more than Taha Abdurrahman. Indeed, even though I do not agree with everything he says, and even though I find his perspective narrow (not shallow, but narrow) at times, I admire this thinker for the way he handles the activity of thinking properly. He came to our country recently. One of the questions he was asked was, “You value Islam so much, but the plight of Muslims is obvious. How will this contradiction be overcome?” The Master replied, “When I talk about human beings and Muslims, I am not talking about concrete people and real situations. I don’t have that luxury, I am a practitioner. I am dealing with the problems of people who have psychological problems, who are troubled, who are worried. So I have to answer your question.

My answer is not as long as you think. It will not be full of political and social remedies, as one might think. Because I am of the opinion that if we don’t change one by one, the expected transformation will never happen. Therefore, I would like to say a few sentences on how we can change ourselves.

We should start by leaving aside the easy, totalizing, simple and cheap solution prescriptions we are used to. Modernity was not our thesis, of course, but we live in the modern world and we cannot know the institutions, concepts and categories of this world better than its founders. Therefore, let us be in the modern world, in its institutions, in its environments, let us work, let us live, but let this life always be in a critical position (and I think criticism is the duty of a Muslim in every living environment. It is not a reflex of discontent or complaining, but of thinking about what could be better).

Let us try to do our best in all activities that do not contradict our fundamental beliefs, and let us take a confident stance that only we can do the best because we believe in the excellence of human beings. Let our criticism be directed at ourselves as much as the work we do, and let us constantly focus on repairing ourselves and what we need to do to become better people.

When we become exemplary people who do our best work, the light of hope will begin to shine everywhere, especially in our families, workplaces and social circles.

Let me put it more concretely: If we strive to be the best person in our respective positions, and if being Muslim comes to mean being a good, hardworking individual with a high sense of artistic appreciation, and if thinkers, scientists, doctors, judges, engineers, artists, academics, and neighbors—respected by the whole world—are Muslim, then the sunrise is near. Otherwise, we will continue for many more years chasing after politicians, superficial ideologues, eloquent speakers with no other skill than rhetoric, self-proclaimed miracle workers, paranoid feudal lords, and cunning Recais.

–Thank you.

*Prof. Dr. Erol Göka

Born in 1959 in Denizli, Türkiye. He is married and has five children. In 1992, he became an associate professor of psychiatry, and in 1998, he was appointed as the Head of the Psychiatry Clinic at Ankara Numune Training and Research Hospital (Ankara Numune Eğitim ve Araştırma Hastanesi). Currently, he serves as the Educational and Administrative Head of the Psychiatry Clinic at the Ankara City Hospital (Ankara Şehir Hastanesi) of the University of Health Sciences (Sağlık Bilimleri Üniversitesi) Faculty of Medicine. He is part of the editorial board of the journal Türkiye Günlüğü and a member of the advisory boards of various journals in the fields of medicine and humanities.

Erol Göka was awarded the 2006 “Intellectual of the Year Award” by the Turkish Writers’ Union (Türkiye Yazarlar Birliği) for his book Türk Grup Davranışı (“Turkish Group Behavior”). In 2008, he received the “Ziya Gökalp Science and Encouragement Award” from the Turkish Hearths (Türk Ocakları).Prominent

Web: erolgoka.net

Mail: [email protected]

Göka’s published books:

Psychology of Turks (Türklerin Psikolojisi, 2008; 2017),

Women, Men, Lovers (Kadınlar, Erkekler, Âşıklar, with Dr. Sema Göka, 2008),

Against the Seven Heavens: Leadership and Fanaticism in the Turks (Yedi Düvele Karşı: Türklerde Liderlik ve Fanatizm, 2009),

Goodbye: Loss, Grief and the Challenges of Life (Hoşçakal: Kayıp, Matem ve Hayatın Zorlukları, 2009; 2018),

The Nomadic Spirit of the Turk (Türk’ün Göçebe Ruhu, 2010; 2019),

Incompatibles: How to Recognize Personalities and Facilitate GettingAlong (Geçimsizler: Kişilikleri Tanıma ve Geçinmeyi Kolaylaştırma Kitabı, with Dr. Murat Beyazyüz, 2011; 2019),

Is the “Truth” Written on a Person’s Face: Recognizing Personality from the Face in theWest, Islam and the World of Science (“Gerçek” İnsanın Yüzünde Yazar mı: Batı, İslâm ve Bilim Dünyasında Kişiliği Yüzden Tanımak, with Dr. Murat Beyazyüz, 2012; 2020),

Does Life Have Meaning? (Hayatın Anlamı Var mı?, 2013; 2019),

Loneliness and Hope: Existential Despair and Exit Today (Yalnızlık ve Umut: Günümüzde Varoluşsal Çaresizlikler ve Çıkış, 2020),

The Enemies of Moderate Muslims Today (Mutedil Müslümanların Günümüzdeki Düşmanları, 2016),

The Internet and Our Psychology: Human in a Technomediatic World (İnternet ve Psikolojimiz: Teknomedyatik Dünyada İnsan, 2017).